I never held a camera in my hand until my second year of college. After trying on four or five majors, none of which fit, I stumbled into journalism. Here I could use my natural curiosity to some advantage. Then, I discovered photojournalism, which was even better—my first drafts of stories were always OK, but I couldn’t learn to rewrite. Photojournalism, I realized, had no second drafts—you only got one chance to get it right.

You can view this article and much more with minimal ads in our brand new app for iOS, iPadOS, and Android.

Like approximately 90% of the photographers I know, my first real inspiration as a photographer was Henri Cartier-Bresson. He seemed to go everywhere in the world and see everything—things invisible to everyone else. He used a small, unobtrusive Leica with one lens and seemed to carry very little else (except money–lots of money). No lights, no assistants, no model release forms, nothing.

This was my fantasy of the ideal photographer’s life.

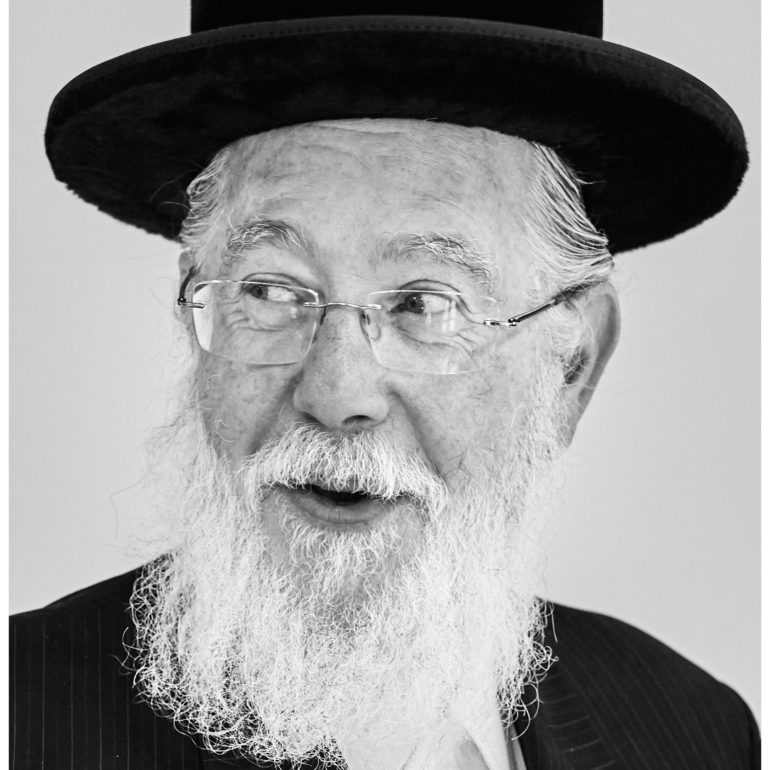

Boyd Hagan

That may be the life some photographers live, but the reality is a bit different for me. When I began getting paid to take photographs, clients like TIME Magazine and The New York Times didn’t care what size your camera was—it had to be 100% reliable, as well as versatile: Nikons were my go-to cameras for that reason.

When I was gasping for breath at 14,000 feet in the Andes while trekking to Machu Picchu with what felt like an 80-lb Nikon in my backpack, or hanging out of a helicopter over Las Vegas at dawn with a camera attached to a 6-pound gyro stabilizer (no IBIS in those days) or setting up lights at the New Jersey Meadowlands to shoot a brand-new Ferrari, with the president of Ferrari and a (very expensive) trained Hollywood rearing horse plus–I had less than 10 minutes to shoot the photo (a day-long anxiety attack), I sometimes thought about my stripped-down fantasy of one-camera/no lights photography.

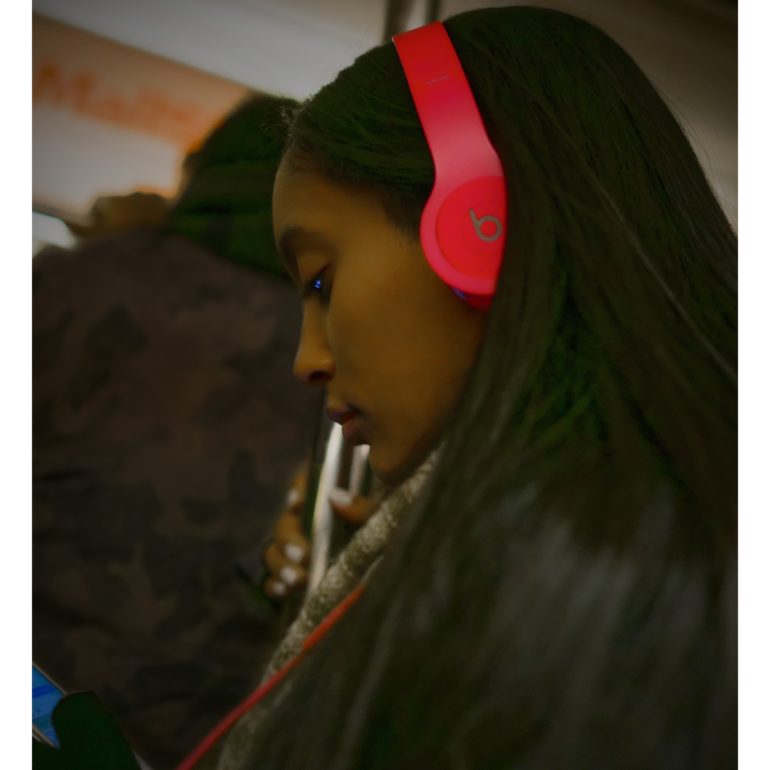

In my personal work, I strive for spontaneity, simplicity, and physical beauty; a big, impressive camera (no matter how technically advanced) isn’t really helpful.

After using a variety of Nikons, Hasselblads, a Sinar 4×5, an 8×10 camera, and various digital cameras, I was still looking for that one camera that could do it all. I had some fun with great little point-and-shoot cameras like the Olympus XA, but I wanted more out of my fantasy camera.

I haven’t found the perfect camera yet, but I did find a close cousin to it.

Boyd Hagan

When I injured my back hauling equipment on a location shoot (no budget for an assistant!), I began looking for something more lightweight that could make excellent photos and save me from surgery. One day, I saw a demonstration of something new: a Sony mirrorless camera—the NEX-5. The photographs looked very good. I sold my Nikon gear and traded for much lighter Sony mirrorless cameras, adding the first full-frame mirrorless A7 in 2013. I continued to upgrade as new Sony cameras were released.

Sony mirrorless cameras were excellent and lighter than Nikons, but still not really the featherweight champion of my dreams.

When I began getting paid to take photographs, clients like TIME Magazine and The New York Times didn’t care what size your camera was—it had to be 100% reliable, as well as versatile.

Boyd Hagan

Then, in 2015, the Sony RX1R II found me.

First and foremost, this camera is smaller and lighter than a Leica M camera. The shutter is as quiet as a Leica M. It has a full-frame 42MP BSI-CMOS image sensor for great low-light performance, with an incredibly sharp fixed Zeiss 35mm f/2.0 lens (designed specifically for the RX1R II). Even more impressive, it has extremely fast and accurate autofocus, with 399 AF points with 25 cross-type contrast detect focus points. Focus peaking is available and frequently in use.

For me, this was close to perfection.

The RX1R II looks like a slightly older brother of Sony’s point and shoot RX100 cameras—it draws no attention to itself. It is possibly the least intimidating professional camera I’ve ever seen.

The cliché that “the best camera is the one you have with you” should be stamped on the back of this camera—it’s 4.5 x 2.6 x 2.8″ and weighs 1.1 lbs. The iPhone 13 Pro Max, while a much better telephone and computer, has a 1/1.65″ image sensor, and measures 6.33 x 3.07 x 0.30″. The RX1R II will fit into a pants pocket.

The van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam has “No Photography” signs, but hundreds of iPhones were shooting photos and video with no interference when I was there recently, so I joined in with the RX1R II and no one noticed.

I have used the RX1R II for street photography, landscapes, portraits, and performing arts photography at Carnegie Hall—even food photography (it has a “macro” mode that allows you to focus as close as 7.8″; not really macro, but closer than normal). It can shoot very serviceable 1080p video, I hear.

That list doesn’t even include my favorite use for the RX1R II: it is an unsurpassed travel camera. In addition to all of the above attributes, the 42MP sensor allows you to severely crop an image and still have really great image quality. I often crop a frame to a 50mm or 85mm angle of view with no visible degradation of the image (at least not online). It’s like having a 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, and even 105mm lens in one itsy bitsy package.

I don’t want to mislead anyone—this is not a perfect camera. The viewfinder is difficult to access and I now use only the LCD monitor (focus peaking makes it easy); the Sony battery is one of the worst I’ve ever come across: I never take the camera out with fewer than four charged batteries. But I can carry extra batteries—I can’t add image quality or superb autofocus that isn’t there, in post processing.

There are some improvements I would love to see in a new version of this camera: the original RX1R had lower resolution and mediocre autofocus, but it did have a great built-in pop-up flash that was extremely useful for fill-flash. That’s something I would pay more for, especially since the RX1R II costs about half as much as a comparable Leica with lower resolution and inferior autofocus.

And, since I already have the RX1R II, I would love to have a similar camera with a wider lens—28mm or 24mm, for instance.

And if Sony, in their infinite wisdom, decides that the world doesn’t need another RX1R camera, I will be content to have this one tucked into my pocket, ready at a moment’s notice to make great images.

Like approximately 90% of the photographers I know, my first real inspiration as a photographer was Henri Cartier-Bresson. He seemed to go everywhere in the world and see everything—things invisible to everyone else. He used a small, unobtrusive Leica with one lens and seemed to carry very little else (except money–lots of money). No lights, no assistants, no model release forms, nothing.

Boyd Hagan

All images were used with permission from Boyd Hagen. Follow him on Instagram! Want to get your work featured? Follow the directions here.