Last Updated on 04/07/2022 by Chris Gampat

The 2022 World Press Photo Winners have been announced, and the images presented here reflect a whole lot of what happens in the world. As an American, the images are fascinating to stare at. It’s impossible for us to see all these stories from the various media agencies. But it’s also often not fed to us. The images are incredible, and cement the fact that photography isn’t going to be replaced by video. Instead, photographers just need to strive to be that much better. As these photos display, it means we need to really get out there and document the world as it happens.

View this article with minimal banner ads in our app for iOS, iPad, and Android. Get no banner ads for $24.99/year.

This year’s 2022 World Press Photo Winners have images that hit me in many different ways. Often I think back to college, and how I literally wanted to be one of these folks. But after doing it for a little while and careful deliberation, I didn’t want to anymore. What these photographers do is dangerous, difficult, physically taxing, and potentially mentally scarring. Having to separate your emotions while documenting what’s happening in front of you is a tough thing to do. But there are also fascinating projects, such as the one you’ll see that was partially computer-generated to prove a point.

We, as passionate photographers, should keep all this in mind as we look through these photos. What’s more, we should celebrate the work these photographers do. Please take a look at the images below. You’ll get one of the best mobile and tablet experiences if you download our app. Otherwise, check this out on a desktop.

Table of Contents

The Cameras Used

The following contains data that we’ve mined using Capture One 22 to figure out the cameras used. We’re focusing on those more than the lenses. But of course, we know that lenses are important. And ultimately, it’s the photographer who fires the shutter.

- Canon 5D Mk IV

- Canon 5D Mk III

- Canon 5D Mk II

- Canon 1Dx

- Canon 1Dx Mk II

- Canon EOS R5

- Canon 6D MK II

- Canon 7D

- Leica M8

- Leica M10

- Sony a7

- Sony a7r III

- Sony a7 II

- Sony a7 III

- Fujifilm XT2

- Fujifilm GFX 50s

- Nikon D6

- Nikon D3

- Nikon D4

- Nikon D3200

- Nikon D800

- Nikon z7 II

- Nikon D750

- Nikon z7

- Nikon D810

- HUAWEI LX1A

- DJI Drones

- Film cameras

An Analysis of Trends

- Nikon and Canon DSLRs are still popular for working photojournalists who’ve used the same gear that’s consistently worked for them for years.

- If we don’t mention a camera associated with a photographer, it’s because we couldn’t find it in the EXIF data.

- Film continues to create great photos.

- Drones and phones remain to be a useful tool for photographers.

- The Nikon z6 and z6 II were designed with photojournalists in mind, yet photojournalists defer to the higher megapixel bodies it seems from Nikon. The exception is their higher-end DSLRs.

- Don’t discredit older cameras! The Leica M8, Canon 5D Mk II, and the original Sony a7 made it on this list!

- This list has three APS-C cameras.

- One medium format digital camera was used.

- The majority of cameras here are full-frame DSLRs and mirrorless cameras.

- We’re a bit stunned to not see the Sony a1 anywhere on this list.

- The winning image was shot with the Canon 5D Mk IV, which has the same sensor as the Canon EOS R.

- Previous awards have had a lot more Fujifilm cameras present.

- A mix of prime lenses and zooms were used.

WORLD PRESS PHOTO OF THE YEAR (Amber Bracken Using a Canon 5D Mk IV)

Kamloops Residential School by Amber Bracken, Canada, for The New York Times

Red dresses hung on crosses along a roadside commemorate children who died at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, an institution created to assimilate Indigenous children, following the detection of as many as 215 unmarked graves, Kamloops, British Columbia, 19 June 2021.

Global jury chair Rena Effendi about this image: “It is a kind of image that sears itself into your memory, it inspires a kind of sensory reaction. I could almost hear the quietness in this photograph, a quiet moment of global reckoning for the history of colonization, not only in Canada but around the world.”

WORLD PRESS PHOTO STORY OF THE YEAR (Matthew Abbott using a Nikon D6)

Fire fighting on country with Warddeken. Third Trip for Nat Geo.

“This is my country.

This is where I recognise myself.

I have a responsibility to manage

it now and into the future”

Andrew Marangurra – Traditional Owner

For thousands of generations, Nawarddeken clan groups lived on their customary estates in the stone country. They were part of a living landscape, integral to the health of the stone country, Nawarddeken walked, camped throughout their lands, each dry season undertaking landscape-scale traditional burning.

With the arrival of Balanda (white people), Nawarddeken began to leave the stone country attracted by Christian missions and government trading posts, opportunities to work in the mining and buffalo industries, and the appeal of larger settlements.

A Nawarddeken diaspora resulted and, by the late 1960s, the Stone Country was largely

depopulated. Nawarddeken elders considered the country orphaned.

During this time, our elders saw and felt the devastation of large wildfires and an increasing number of feral animals impacting biodiversity and cultural sites. Their concern was matched only by their desire and motivation to return to country, to once again look after the Stone country, and maintain and pass on their knowledge to future generations.

In the 1970s a return to country movement began in Australia, which resulted in Nawarddeken moving back to outstation communities, the traditional homes in the stone country.

In 2002 after decades spent bringing other Nawarddeken back to country, traditional owner Bardayal Lofty Nadjamerrek returned to his childhood home at Kabulwarnamyo to establish the first of three Warddeken ranger bases, providing employment in the region and allowing landowners to make a living on country. Establishing their own schools, housing and infrastructure.

Warddeken Rangers were the first in the world to earn carbon credits from the traditional burning of country.

Saving Forests with Fire by Matthew Abbott, Australia, for National Geographic/Panos Pictures

Indigenous Australians strategically burn land in a practice known as cool burning, in which fires move slowly, burn only the undergrowth, and remove the build-up of fuel that feeds bigger blazes. The Nawarddeken people of West Arnhem Land, Australia, have been practicing controlled cool burns for tens of thousands of years and see fire as a tool to manage their 1.39 million hectare homeland. Warddeken rangers combine traditional knowledge with contemporary technologies to prevent wildfires, thereby decreasing climate-heating CO2.

Global jury chair Rena Effendi about this story: “It was so well put together that you cannot even think of the images in disparate ways. You look at it as a whole, and it was a seamless narrative.”

WORLD PRESS PHOTO LONG-TERM PROJECT AWARD (Lalo de Almeida Using the Canon 5D Mk III and a DJI Drone)

These communities, which are mostly extractivists, depend on the territory for their livelihood. With no prospects for change in the short term, young people end up migrating to the cities in search of work while the communities become increasingly empty and politically weaker.

Agribusiness is one of President Bolsonaro’s main pillars of political support, especially because they share the same view that environmental preservation is an obstacle to development.

This government has weakened environmental enforcement agencies and non-governmental organizations, which act as a counterweight, albeit unequal, to the predatory model of exploitation in the Amazon region.

Amazonian Dystopia by Lalo de Almeida, Brazil, for Folha de São Paulo/Panos Pictures

The Amazon rainforest is under great threat, as deforestation, mining, infrastructural development and exploitation of other natural resources gain momentum under President Jair Bolsonaro’s environmentally regressive policies. Since 2019, devastation of the Brazilian Amazon has been running at its fastest pace in a decade. An area of extraordinary biodiversity, the Amazon is also home to more than 350 different Indigenous groups. The exploitation of the Amazon has a number of social impacts, particularly on Indigenous communities who are forced to deal with significant degradation of their environment, as well as their way of life

Global jury chair Rena Effendi about this story: “This project portrays something that does not just have negative effects on the local community but also globally, as it triggers a chain of reactions on a global level.”

The Winners

Here’s a list of the winners

Open World Format: Isadora Romero Using a Sony a7 and Sony a7r III

Africa Singles: Faiz Abubakr Mohamad Using a Nikon D750

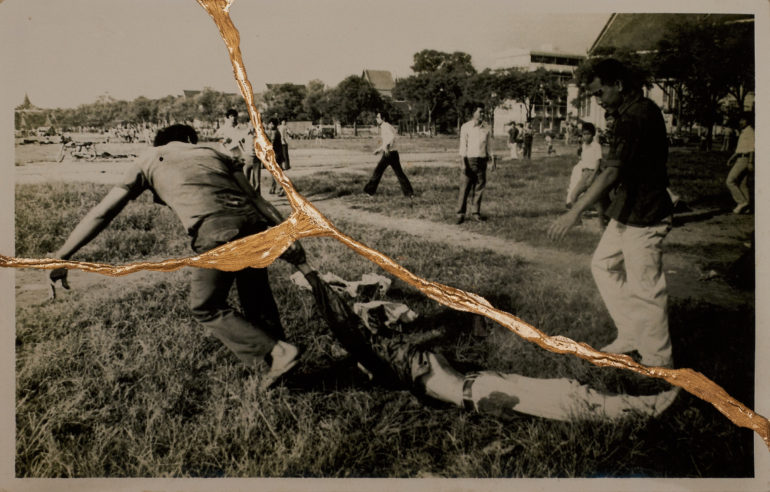

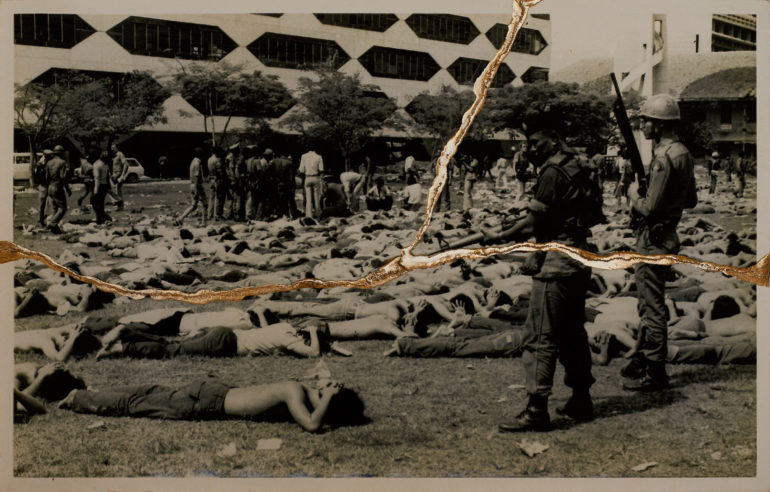

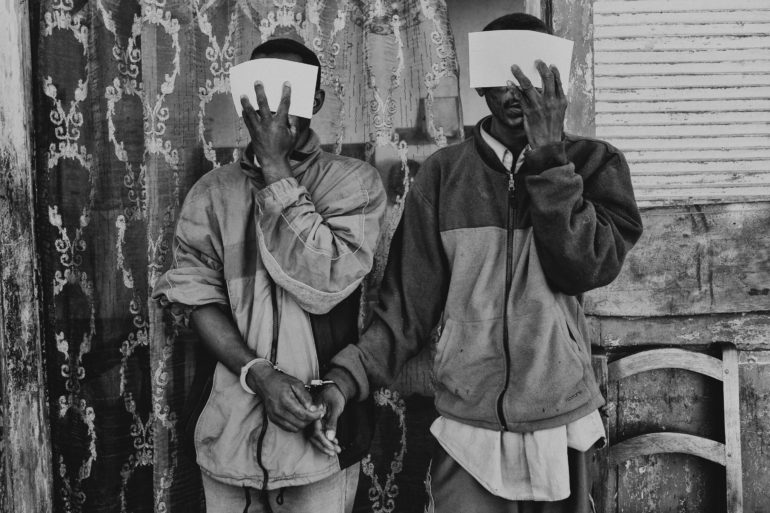

Africa Stories: Kola Sulaimon (Sodiq Adelakun Adekola)

The July 5 attack in Nigeria’s northwest Kaduna state was just the latest mass abduction at a school or college as kidnap gangs seeking quick ransoms zero in on soft target of young students.

Armed kidnappings for ransom along highways, and from homes and businesses now make almost daily newspaper headlines in Africa’s most populous country. (Photo by Kola Sulaimon / AFP)

The July 5 attack in Nigeria’s northwest Kaduna state was just the latest mass abduction at a school or college as kidnap gangs seeking quick ransoms zero in on soft target of young students.

Armed kidnappings for ransom along highways, and from homes and businesses now make almost daily newspaper headlines in Africa’s most populous country. (Photo by Kola Sulaimon / AFP)

African Long Term Projects: Rijasolo Riva Using a Canon 5D Mk II, Canon 5D Mk III, and Leica M8

Les dahalo fonctionnent comme une mafia. Lourdement armés de fusils à deux ou cinq coups de type Baikal, ou d’armes de guerre type kalachnikov, ils vivent en communauté dans des villages coupés du reste du monde en autarcie complète et rackettent et volent régulièrement les villages voisins pour leur imposer une forme d’allégeance. Cette loyauté acquise sous la menace leur permet d’acheter le silence de la population locale au cas où des opérations militaires “anti-dahalo” sont menées. Il est communément admis que cette pratique du vol de zébu est issue d’une tradition venant des ethnies du Sud de Madagascar (Antesaka, Antandroy, Sara, etc) qui ont migré petit à petit vers le Nord dans les années 90/2000.

L’opération Tandroka était une opération militaire d’envergure, lancé par les autorités en décembre 2012 pour tenter d’éradiquer le phénomène de vols et traffics de zébus. Les militaires ont rapidemment étaient accusés par Amnesty International d’avoir commis des exactions et tortures sur des villageois pendant leur raids.

Les bouviers travaillent pour un grand éleveur de bétail et peuvent être parfois issus de la même famille ou clan que celui de leur patron. Le métier de bouvier est l’une des activités professionnelles les plus pratiquées par les jeunes hommes en zone rural et dans des régions qui produisent beaucoup de zébus comme ici la région Melaky dans l’Ouest de Madagascar. Ces bouviers sont payés à la tâche : pour chaque barea sauvage capturé, l’équipe est payée 100.000 Ariary (20 euros).

Les “barea” sont les zébus endémiques de Madagascar réputés plus robustes, plus imposants, mais aussi plus difficiles à dompter par rapport au zébu commun historiquement originaire d’Inde.

Le zébu est un animal emblématique dans la culture malgache surtout en zone rural. Il est tantôt un outil de travail pour aider les paysans à labourer et cultiver la terre, tantôt un animal sâcré que l’on sacrifie lors de cérémonie traditionnelle pour honorer la mémoire des ancêtres. Mais c’est finalement en ville que le zébu est le plus prisé car sa viande est particulièrement recherchée par les restaurants et les ménages qui ont les moyens d’en acheter.

Les “barea” sont les zébus endémiques de Madagascar réputés plus robustes, plus imposants, mais aussi plus difficiles à dompter par rapport au zébu commun historiquement originaire d’Inde.

Le zébu est un animal emblématique dans la culture malgache surtout en zone rural. Il est tantôt un outil de travail pour aider les paysans à labourer et cultiver la terre, tantôt un animal sâcré que l’on sacrifie lors de cérémonie traditionnelle pour honorer la mémoire des ancêtres. Mais c’est finalement en ville que le zébu est le plus prisé car sa viande est particulièrement recherchée par les restaurants et les ménages qui ont les moyens d’en acheter.

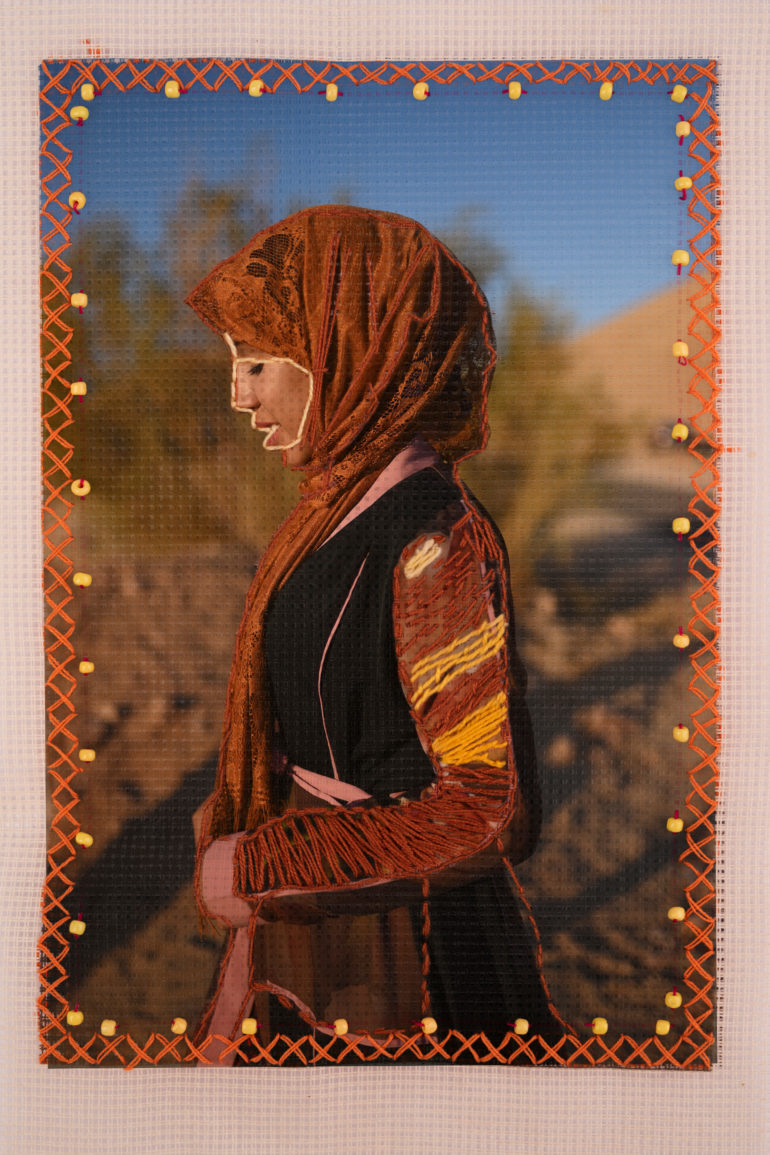

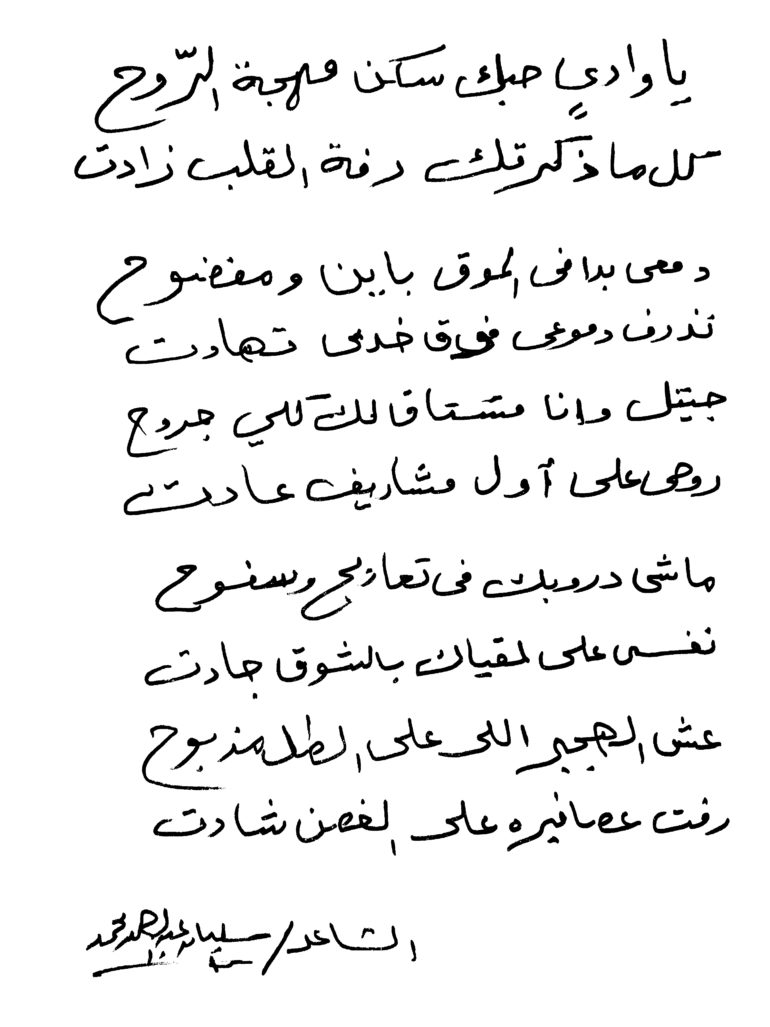

Africa Open Format: Rehab Eldalil Using the Nikon Z7, Nikon D810, and Huawei LX1A

Seliman manages an ecolodge with his cousins in Gharba valley but as the pandemic spreads throughout Egypt, less and less guests come to stay at the ecolodge and now the family redirects their focus on the family gardens. “We don’t have Corona here, but we are affected by it. Look, these plants are our face masks.” says Seliman.

Whenever I see you my heart grows

I come to you in longing full of pains

My soul returns to me as I approach your grounds

By Seliman Abdel Rahman

Africa Honorable Mention: Amanuel Sileshi Using Sony a7 II and Sony a7 III

Asia Singles: Fatima Shbair using the Fujifilm XT2

Asia Stories: Bram Janssen Using the Sony a7 III

Asia Open Format: Kosuke Okahara

Asia Honorable Mention: Dar Yasin Using the Canon 1D X and Canon 1D X Mk II

Europe Singles: Konstantinos Tsakalidis Using Canon 5D Mk IV

Europe Stories: Nanna Heitmann Using Leica M10, Film, and the Canon EOS R5

Europe Long Term Projects: Guillaume Herbaut Using the Nikon D3, Nikon D800, and the Nikon z7 II

Cheminots Park, the Lenin statue was destroyed in the night of December 8-9, 2013.

Ukraine, Kotovsk, 19 décembre 2013

Parc des Cheminots, la statue de Lénine a été détruite dans la nuit du 8 au 9 Décembre 2013.

Guillaume Herbaut / Agence VU

Hrushevskoho street. Since January 21, violent confrontations take place between law enforcement and pro-EU protestors. The special anti-riot units, the Berkouts,

use weapons against the masses. At the end of the day, they count five dead and many hundred wounded.

Ukraine, Kiev, 22 janvier 2014

Rue Hrushevskoho. Des affrontements violents se déroulent entre forces de l’ordre et manifestants pro-européens depuis le 21 janvier. Les unités spéciales antiémeutes, les Berkouts, utilisent des armes à feu contre la foule. À la fin de la journée, on dénombre cinq morts et plusieurs centaines de blessés.

Guillaume Herbaut / Agence VU

Women making ghillie camouflage gear for snipers at the Novy Mariupol center, an organization that collects equipment for Ukrainian soldiers.

Ukraine, Marioupol, 29 septembre 2014

Des femmes préparent une tenue de camouflage pour sniper dans les locaux de Novy Marioupol, une organisation collectant du matériel pour les forces militaires ukrainiennes.

Guillaume Herbaut / Agence VU

Fortifications on the beach of the town of Shyrokyne which is located along the Sea of Azov and is today on the front line.

Ukraine, Shyrokyne, 29 novembre 2021

Fortifications sur la plage de La ville de Shyrokyne qui est située le long de la mer d’Azov et est aujourd’hui sur la ligne de front.

Guillaume Herbaut / Agence VU

Europe Open Format: Jonas Bendiksen Using Sony a7r III

Two fake news producers who do not want to be identified pose with ‘Anonymous masks’ on. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

A man keeps warm by an oil barrel fire, in front of the closed steel smelter which was once a cornerstone of Veles industry. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

Natasha editing content for the fake news website she works for, with a painting of the God Veles and a bear in the background. Veles was a anceint Slavic god of Mischief, chaos and magic, and often took the shpae of a bear himself. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

A bear comes down for a drink of water at the banks of the Vardar river, which runs through the town. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

Armed police stand guard on the outskirts of Veles. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

A local couple who make their lviing of running a fake news website (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

Tamara, a local woman who writes for several of Veles fake news sites, poses for a portrait (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

The laptop of the fake news producer lies on the kitchen counter in a Veles apartment. (fictional caption).

‘The Book of Veles’ is a photographic exploration of the phenomena of fake news and synthetic information. The book was published in April 2021, appearing to be an ordinary documentary photo book about the town of Veles in North Macedonia. The town placed itself on the world map in 2016 as an epicenter for the production of fake news, when local youth set up hundreds of news websites that pretended to be American news portals. These sites, with names such as NewYorkTimesPolitics.com, spread to millions of people through Facebook and Twitter’s algorithms. While the goal of the sites’ creators was simply to earn money through banner ads, they could also have inadvertently have had a real impact on the election of Donald Trump. The book also weaves in a story about a mischievous pre-Christian pagan bear-god called Veles and the 1919 ‘discovery’ of a forged ‘ancient’ manuscript called the Book of Veles.

After my book had been sold for half a year, had been shared on my social media channels and had even been screened at a photojournalism festival, I revealed (through a fake social media profile) that the whole photographic project itself was a forgery: All the people pictured in the book are in fact computer-generated 3D models which I posed and inserted into empty background tableaus from Veles. Many of the animals and important objects in the series were also non-camera-based renderings. The text in the book was written by an AI machine learning system called GPT-2. In essence, Book of Veles is a fake story about real people who made fake news.

Europe Honorable Mention: Mary Gelman using the Canon 6D Mk II and scans

North and Central America Stories: Ismail Ferdous using the Fujifilm GFX 50s and Film

North and Central America Long Term Project: Louie Palu using an Unknown Camera

North and Central America Open Format: Yael Martinez the Canon EOS R5

An elder in the Garza hill.For the Na savi people, elders are respected since they contain wisdom and connection with our mother earth.

Every December 31, the Na Savi indigenous communities climb the Cerro de la Garza to perform rituals that commemorate the end and beginning of a cycle.

Guerrero Mexico On December 31 2020.

North and Central America Honorable Mention: Sarah Reingewirtz Using the Nikon D4 and Nikon D5

South America Single: Vladimir Encina Using the Nikon D3200

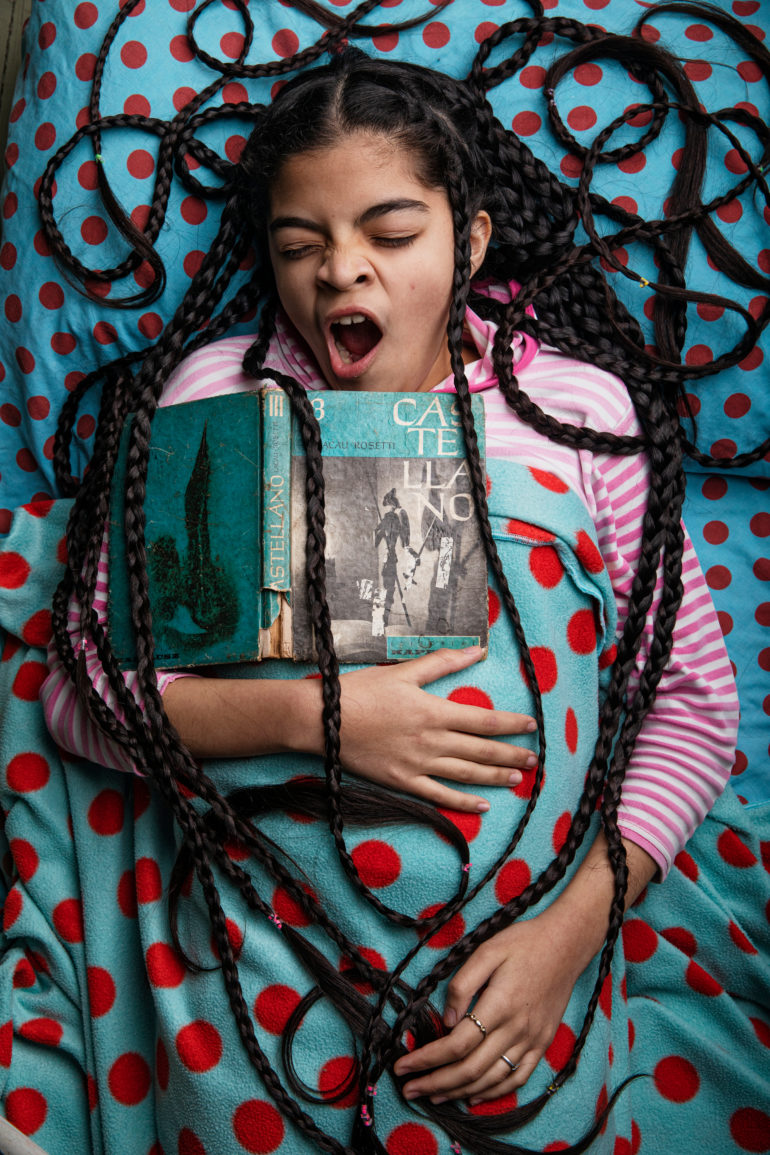

South America Stories: Irina Werning using the Canon 5D Mk IV

Antonella poses outside the Univeridad de Ingenieria de Buenos Aires, place where she asked her father to take her. She wanted to have her portrait taken there because her ambition is to study engineering after finishing school.

NOTE: The portrait was taken with the explicit consent and in full cooperation with the subject’s mother. Both the parents and the subject were adequately informed of the nature, purpose and distribution of the project.

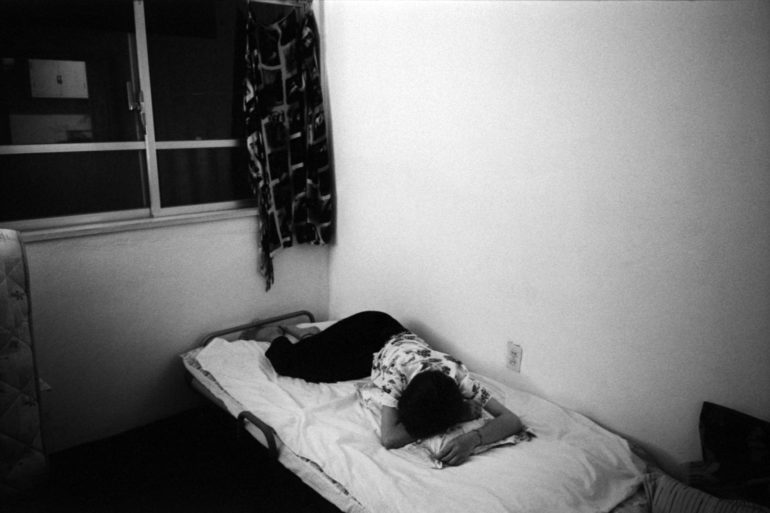

In this picture, I captured the moment she yawns while studying language. Sometimes she studies from bed as she lacks the motivation to get up.

NOTE: The portrait was taken with the explicit consent and in full cooperation with the subject’s mother. Both the parents and the subject were adequately informed of the nature, purpose and distribution of the project.

Antonella washed a black faux fur blanket the family has on top of her parents’ bed. She poses for her portrait in front of the fur and asks me to take a picture of her hair to celebrate it because it means so much

NOTE: The portrait was taken with the explicit consent and in full cooperation with the subject’s mother. Both the parents and the subject were adequately informed of the nature, purpose and distribution of the project.

Antonella was studying via zoom with friends for her Biology course during the weekend. She had to do a group project and each student would take turns to participate with parents monitoring the participation. (June 2021, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Antonella is very lucky that her parents are truly obsessed that their daughter keeps up to date with her education and organize via watsap with other mothers group studies virtual get togethers. Her sister shares the small room with her and stays in her bed when she is in class because the room is very small. Carolina is 23 and she helps her parents organize Antonella’s virtual schedule and make sure she attends all classes and does her group projects with her school mates.

NOTE: The portrait was taken with the explicit consent and in full cooperation with the subject’s mother. Both the parents and the subject were adequately informed of the nature, purpose and distribution of the project.

South America Honorable Mention: Viviana Peretti using a Rolleiflex

Southeast Asia and Oceania: Anonymous for the NY Times Using the Canon 6D (No, Seriously)

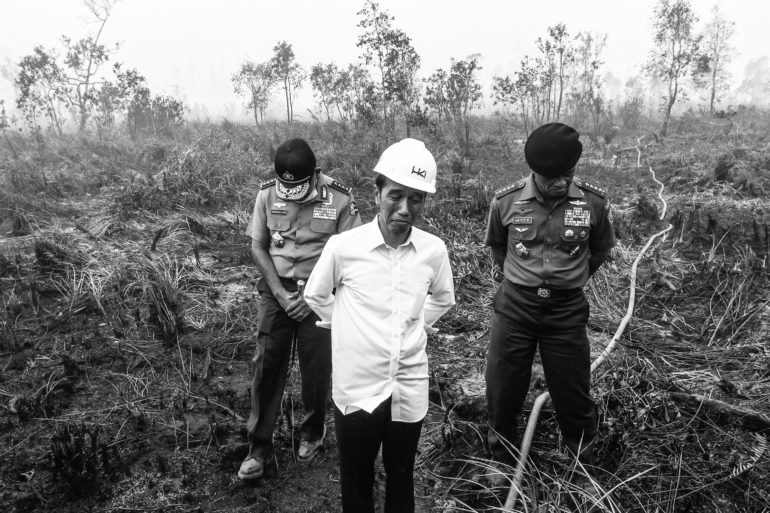

Southeast Asia and Oceania: Abriansyah Liberto using the Canon 7D and Canon 5D Mk II

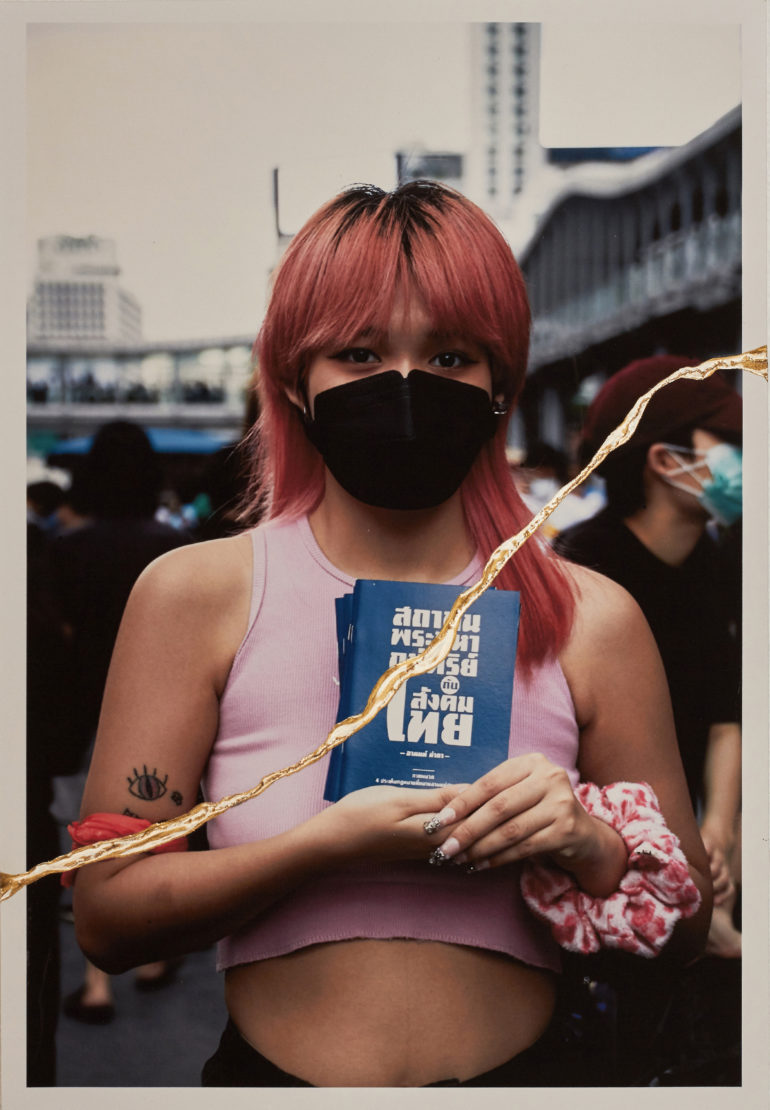

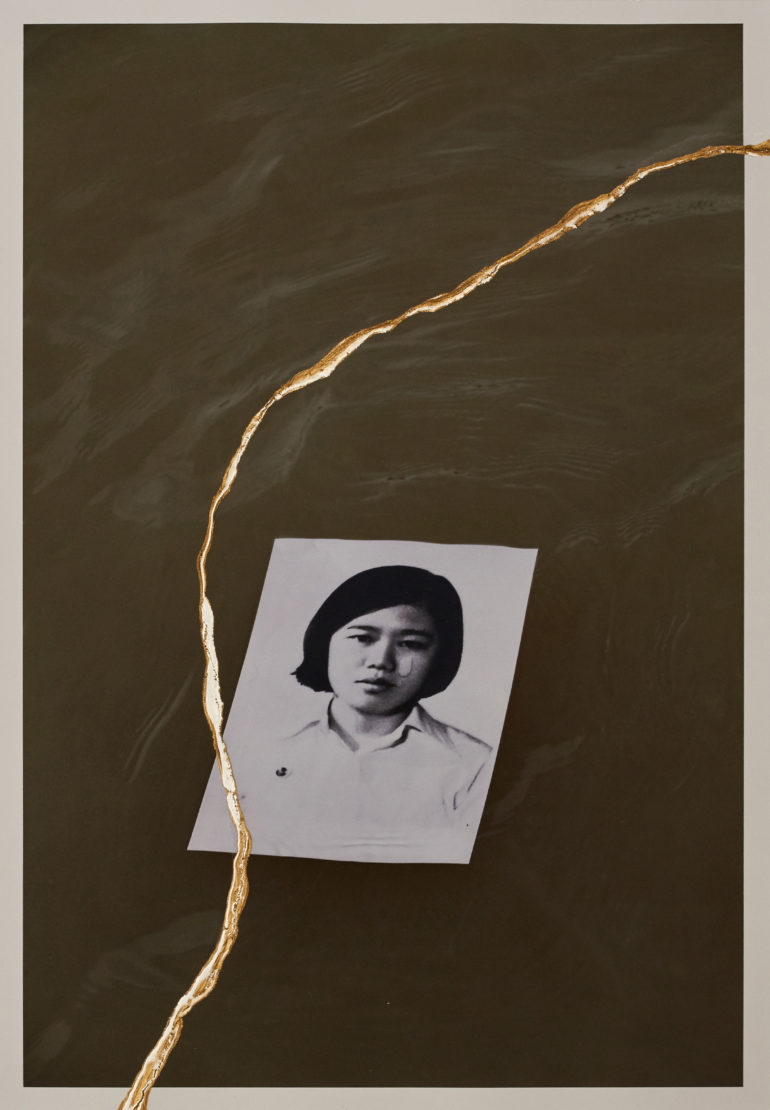

Southeast Asia and Oceania Open Format: Charinthorn Rachurutchata

Southeast Asia and Oceania Honorable Mention: Ta Mwe Sacca

You can see more over at the World Press Photos official website.