Last Updated on 10/26/2020 by Chris Gampat

Declassified is an original Phoblographer series that digs deep into historical documents to examine how the government used photography.

We previously reported on how aerial color film photography was a headache for the CIA. But the problem wasn’t just with aerial photography. One document in the late 1960s tells about all the checks and concerns there were about color film. Today, you’d easily think it was standard fare. The transition from black and white was a slow one, though. Color didn’t really become the norm until they started to move to digital. One would think that slide film would have done the trick, but that’s not the case. It seemed like everyone wanted it. But the labs, the treasury, and the higher-ups all thought it would make things too complicated. The CIA had many concerns. Let’s put this into perspective.

So what was wrong with color photography? Let’s start with why it was needed. Agents involved in a specific mission conveyed the need for it. To them, the black and white film wasn’t cutting it. Color provided details they couldn’t get with a black and white film. Black and white, mind you, gave more resolution, but color helped them tell the differences in things like typography amongst a myriad of other factors. One of the biggest was cloud detail. “Clouds have an adverse effect on all photography,” states the document. “The loss of information in cloud shadows is more pronounced in color photography…” The record continued to say that the dynamic range of color photography is seriously lacking.

What’s more, a photo of a person in black and white doesn’t tell the story like a color photo does. So, the CIA weighed the pros and cons of the resolution loss. The higher-ups really needed to understand if the tradeoff was worth it. At a later point, the agency ended up using both.

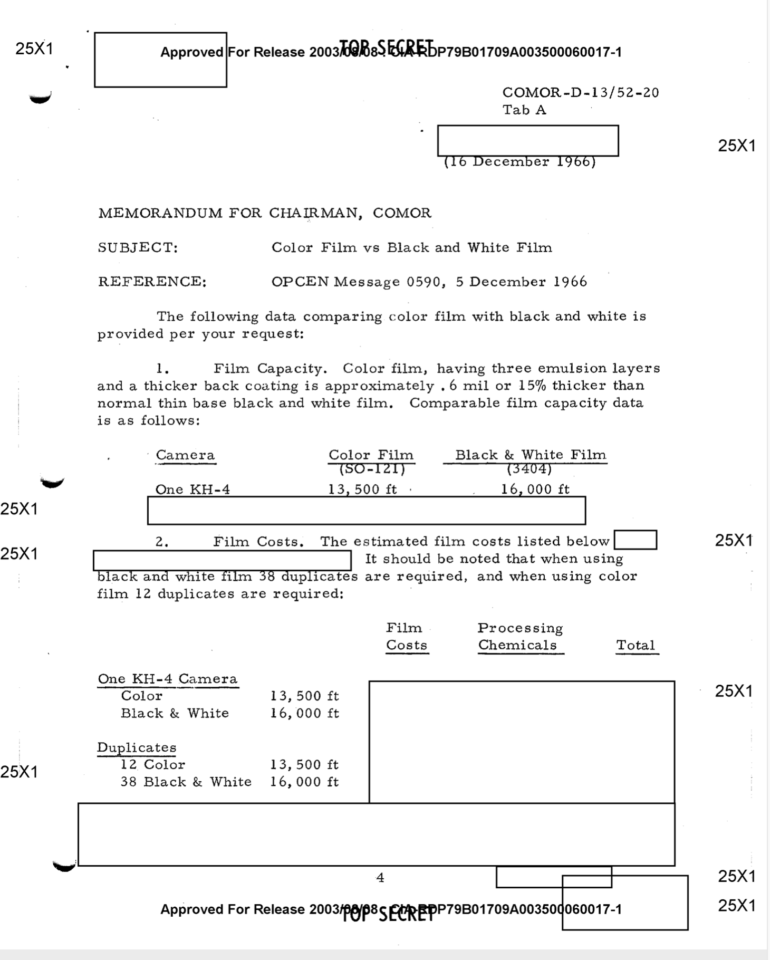

The first concern: the cost. The CIA had no idea what sort of costs the film itself and processing would be. Those had a bunch of other problems tied to it. For example, how much each “community” would need, their individual costs, etc.

The CIA’s other concern was the long term durability. The early film had problems galore, and arguably still does. It was temperamental and didn’t like various types of weather. This has always been the case. When you buy a film, it expires after time. So to prevent that from happening, you put it in the freezer. Film is an organic material. So just like you’d store frozen meat in the freezer, you do the same for film. That way, the film can last way after the expiration. The CIA took this knowledge and ran with it. They estimated it would take 5 to 8 years before profound changes happened.

What’s more, the film needed to be developed ASAP. This is sort of like what customers complain about with modern CineStill. When you shoot it, you need to develop it right away.

All of these problems wouldn’t really go away. The CIA earlier on had concluded that they needed both color and black and white. But move to full-color photography wasn’t really impressing everyone. It continued to be a headache for many years. Though color film and the processing got progressively better, they still ended up using both. Color improved, but so too did black and white. To this date, I’m still impressed by some black and white film scans. Acros is great. Kodak T-Max 400 is also stellar. Lots of film photographers still reach for Tri-X. But digital is still the most common. Today, the agency obviously goes digital.

Lead photo by Ken Lund and used with Creative Commons Permissions.