Last Updated on 10/01/2020 by Chris Gampat

PhotoPlus Expo is the epitome of the autumnal photographic conference: an industry tradition of networking, investigating and testing out new products, asking experts questions, and listening to presentations from inspiring and talented brand-sponsored photographers.

That said, without question, when I attend this conference every year, my fellow attendees are more often male in identification. It’s a commonly acknowledged fact with other women in attendance and is beginning to get noticed by other parts of the industry as well. As such, I was given a critical lens through which to examine PPE (as a test model for conferences in general, a sample subject if you will): How can conferences make themselves more accessible to women, and what presently contributes to them being male-dominated?

I acknowledge that my experiment does not account for booth reps being on a 10-min break or lunch break, so please note the inherently variable nature of my loose investigation. One of the first things I noticed was the number of female representatives for various brands on the floor. Most had a majority of male staffers. I counted 15 reps at Canon, and only two of them were women; Fujifilm had five, one was a woman, and Zeiss had seven, with only one woman. Nikon, Tamron, Digital Transitions, and Kase Filters were more evenly balanced. Overall, there was a distinctly lower percentage of female staffers in the booth. It was significantly better than previous years, showing how far we’ve come, but it also shows how far we have to go as an industry.

This may seem like a small, insignificant thing, but as a woman in the field, I can tell you this is a significant contributor to how accessible a conference feels. Far too often, asking questions in our community as a female photographer is followed by judgment, condescension, or the discrediting of overall expertise in the field. In an industry such as ours, women already feel a substantial amount of imposter syndrome. Having only male representatives or predominantly male representatives makes it more intimidating for a woman to ask questions. In all truth, it shouldn’t matter who is asking the question. But, until our community creates a more open, accepting circle, it does affect the comfort level and accessibility of the brand in question. Asking another woman a question I have, or telling her about an issue I’m experiencing, feels safe. I know she won’t judge me on my technical knowledge, or dismiss my skill as a photographer for asking a ‘stupid’ or ‘ignorant’ question. That’s not to say men can’t show up that way too, but rather that it’s a 50/50 thing. Sometimes, it’s just as communicative and accepting, and other times, it’s belittling, dismissive, or rude. It often feels like you’re being spoken to as if you’re a beginner, and it’s incredibly alienating. It makes me not want to ask questions at all, as I don’t want to have to defend my intelligence just because I want clarification on one component or aspect. Our industry is filled with gearheads and tech junkies. When that sub-group weaponizes that knowledge against the female community, it’s hard to know who you can admit your learning gaps to without feeling like you’re opening yourself up to being attacked. Having more female representatives in the booths is one of the best, most straightforward ways to create a space that feels safe for women to ask questions, seek clarification, and explore software/equipment they want to better understand.

Then there are the gawkers. Far too often, we see the classic model-photographer trope that’s gotten all too old and tired: the 10-20 older white guys all circled around a young, svelte, often sexily styled young woman. It’s never a male model and it’s rarely female photographers. On the surface, it’s innocent enough. The reality is most of the male photographers are genuinely just testing out gear, whether it be lenses, bodies, or lighting equipment, and the model is only the model they hired. As a woman, it makes my skin crawl when I see it. There’s a predatory vibe that emanates from it; I don’t even want to test the gear in that circle of photographers. It’s this subtle but undeniable reminder of the constant male gaze; women are to be the beautifully observed, while the men do the voyeuristic watching. I was impressed with both Nikon and Canon’s approach this year; they helped shift away from this classic crux. Canon embraced creativity and used a daily fashion show, comprised of both men and women in various kinds of styles. This provided an excellent, tangible way to test gear in a much more neutral, less alienating environment. Nikon wasn’t quite as unique, but had both male and female models working concurrently near each other; a clear balance. When we create shifts where it’s not always young, attractive women in front of the lens and older white men behind the camera, we create a more inviting community for everyone.

Then there’s the representation of women on the walls. I hate to say it, but just about every major brand abysmally failed my simple test of ‘is there equal representation?’ The first component I started with was counting the number of female vs. male photographers featured in the gallery displays of the brands. I knew it would be bad, but I was surprised by how horrendously unbalanced it was; Tamron featured 11 artists and only two were women; Canon had 17 artists and five were women; Nikon failed twice over with their winners’ gallery and general display, both of which featured eight artists, with only one woman in each; Epson had 14 artists, and only two of which were women; Sigma had seven artists, with two women; Fujifilm showcased six artists, only one was a woman. Olympus was the best of the bunch, and still didn’t have a 50/50 split; they highlighted a wall of 30 artists, seven of which were solo women, and four were couples. So, of 30 slots, women took barely one third. Women are a significant force for investing in photography equipment, and yet, consistently across all brands, our work is not recognized, not highlighted, and not featured. It’s still very much a man’s world when it comes to brand sponsorship, support, and validation. We don’t see brands truly embracing women as artists except as marketing tools to sell said equipment, and the pandering isn’t as opaque as they want it to be. Many brands want to appear as forward-thinking when it comes to women in the industry. However, many are failing to see the flaws in their approaches, using women as objects to market their materials while thinking it’s highlighting women. When women’s work is showing up as much as men’s on gallery walls, that’s when brands have embraced the female artist, and I hope I get to see that soon.

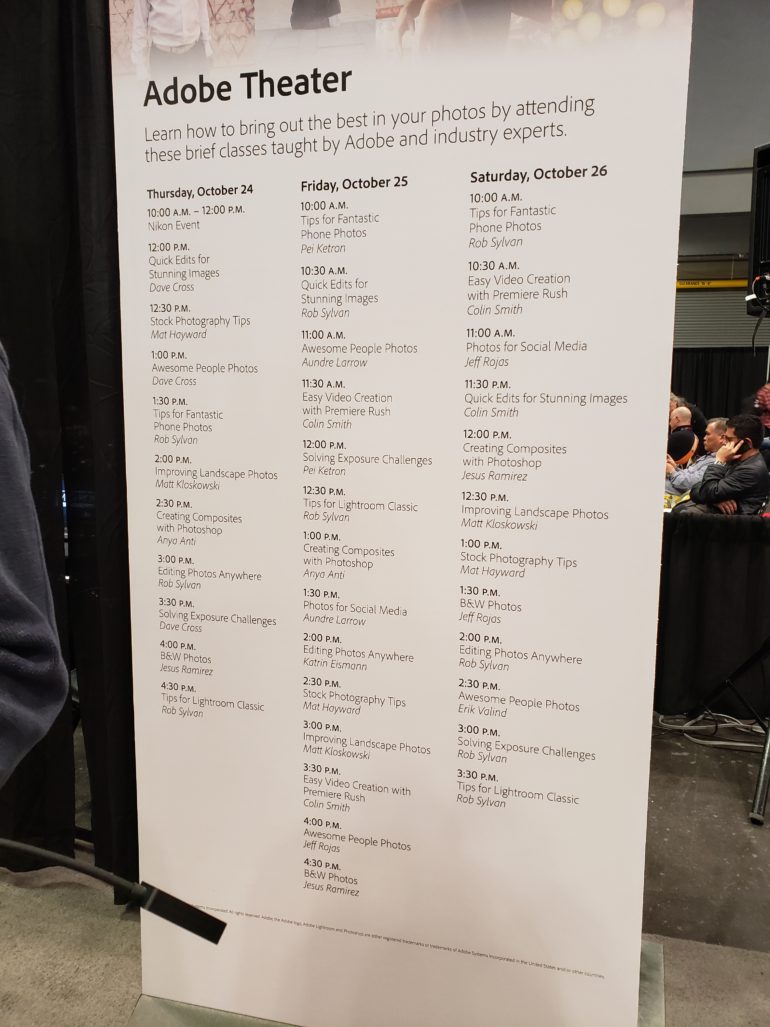

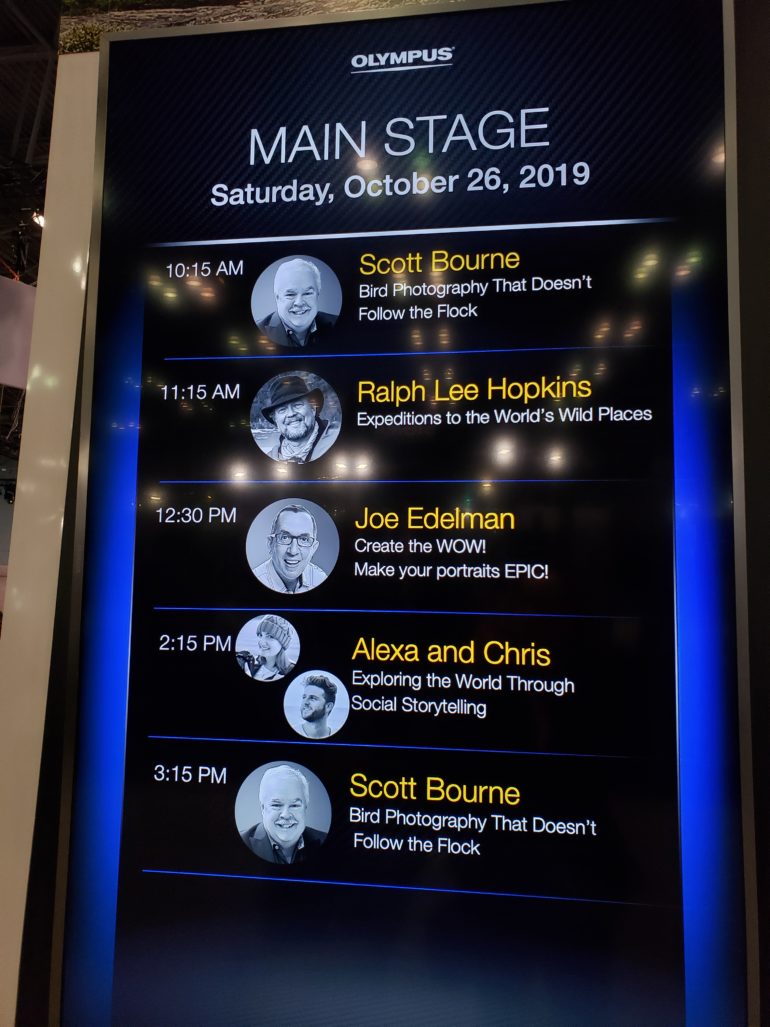

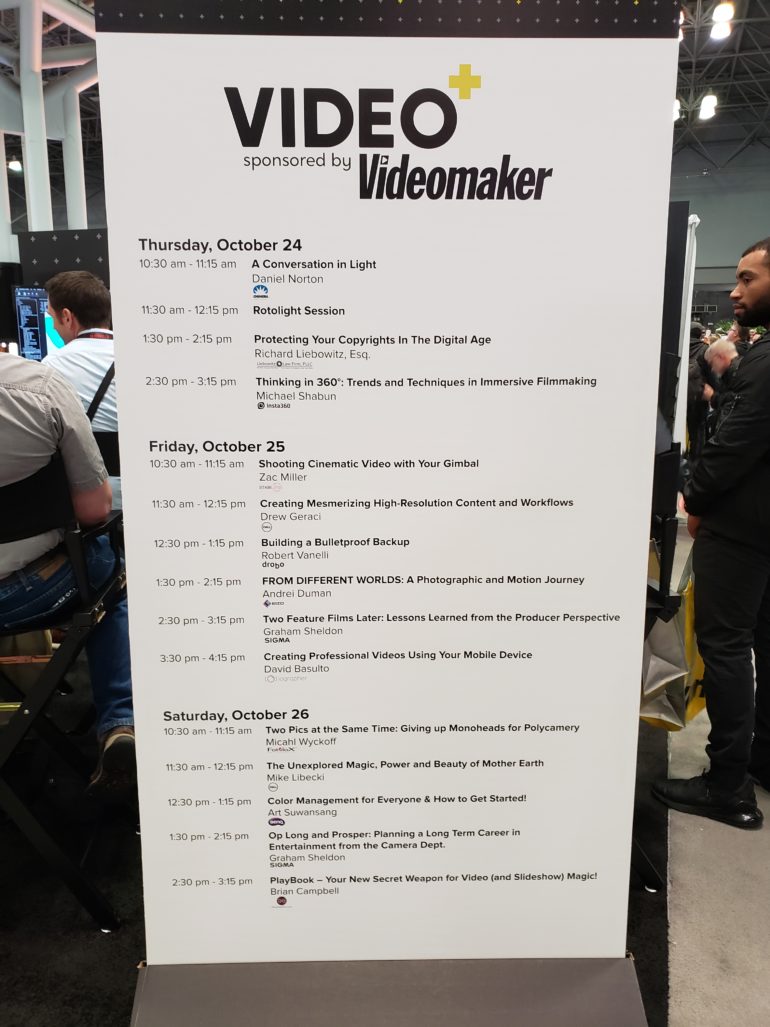

The lack of female presenters also ties to the last point I made. Even with the #MeToo movement, the Sony Alpha Female/We Women/Female in Focus, there was a massive shortage of women on the stages across the board. Some brands were better, such as Canon, but other brands, like Rotolight, didn’t have a single female presenter. Unique Photo had seven male presenters to their two female presenters over the three days; both Sigma and Olympus only had one woman, appearing in partnership with a man on their Saturday schedule; Adobe only had one woman on the 1st day, three of 10 on the 2nd day, and no women at all the 3rd day. In total, they featured nine men and only three women, so 3x more men than women. And Video sponsored by Videomaker didn’t manage to have a single female presenter over the entire three days.

There’s still an evident lack of recognition of women as experts in the industry, and a big part of that stems from not seeing women as leaders on the forefront, speaking as openly and often as the male photographers we frequently idolize. This lack of vocal representation carries into the journalistic side of the industry as well. When the Phoblographer staff went to one of Tamron’s press announcements, I was disappointed to find that I was only one of three women in the room, when there were at least 20 members of the press there. If we aren’t promoting women’s voices in the discussions, is it any wonder that women feel so alienated? Not to mention the fact that feedback would be inherently different, and just as important to note. Everyone’s gauge for reviewing equipment is unique, and having female perspectives on that side of the industry is just as critical to creating a more inviting community for women. A buff dude might not see a heavy lens as an impediment, but a female gear reviewer might speak to the ergonomics in an entirely different way. When we only have men on the reporting side of the field, we lack (and subsequently fail to notice) female feedback, which should be taken into account as much as feedback from male counterparts. What we should be asking ourselves is, why did no one else look at that group of reporters and wonder where the women were?

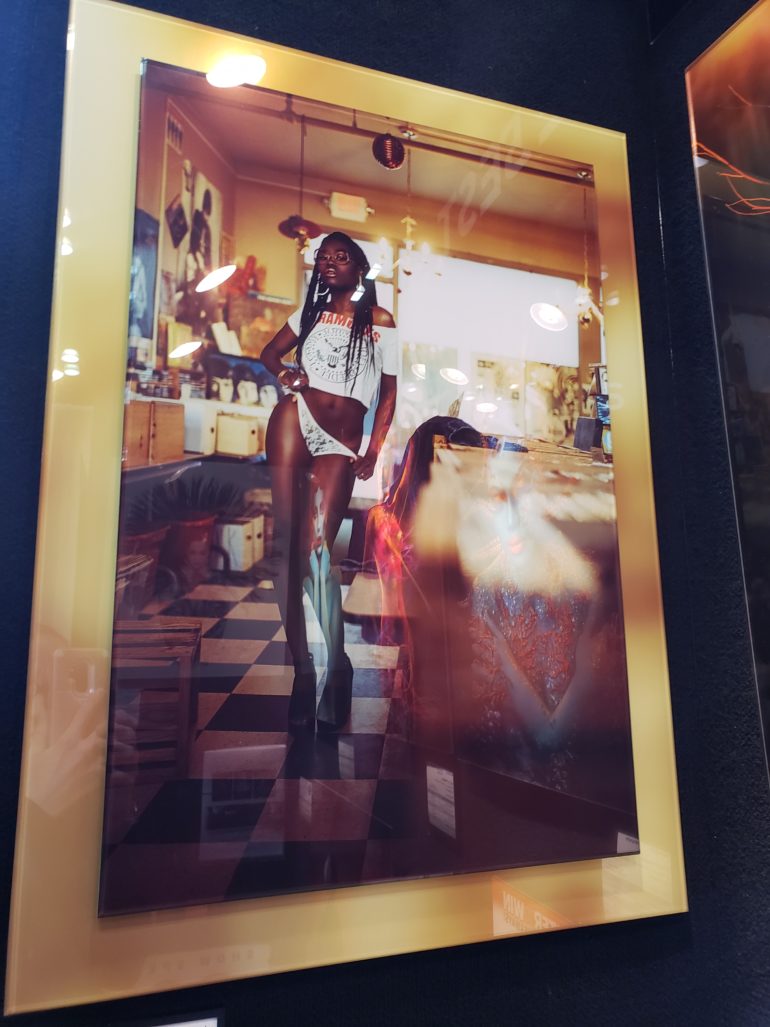

Then, as always, there’s the actual content within the images on the walls themselves. I can’t wait for the day where I’m not walking past dozens of sexualized and objectifying images, a constant assault on my desire to be seen as a human being instead of a sex object. Acrylic Press was probably the worst perpetrator; their booth was filled with naked or nearly naked ‘muses.’ They certainly made sure to put their perspective front and center, with an enormous photograph of a woman dressed in a sheer red dress, with lace appliques barely covering her nipples and breasts. Couple that with the body painting images, and a strangely disjointed portrait of a woman in a t-shirt, heels, and underwear, and I could barely tolerate stepping into the booth just to take photographs. That’s not to say we should never have sexy, erotic, or suggestive images. It would just be nice to have that as one of many types of photography, rather than the sad, old, tired norm of men’s inspiration, born out of voyeuristic fascinations and fantasies. At the very least guys, get as inspired by your own anatomy as you are with women’s. At least a level playing field of seeing pecs and penises everywhere would feel a little less one-sided. (And if that idea makes you uncomfortable, welcome to my world. Nice of you to join me here!)

Obviously, our industry is constantly trying to improve, take these issues on, and grow to be more accepting and inviting. That said, these are just a few of the small, subtle ways women don’t yet feel fully like part of the community. When we can really, truly feel like equal counterparts in our field; when our work is featured on the walls instead of our bodies being the content in the images; when we can hear women talk about their processes and approaches without it feeling niche; that’s when conferences like PhotoPlus Expo will feel like a true welcome wagon instead of a wolf in sheep’s clothing, waiting to devour us whole.