If you loved our feature on how old school photography studios are standing out today, here’s our full interview with 20×24 Studio Berlin’s Markus Mahla for additional reading.

We’re confident that some of you are shocked that the film industry is still alive and kicking. If you fall into this camp, you’d be even more astonished to find out that even older, more ancient, antiquated photography processes — tintypes and ambrotypes — are still around. Best of all, you can book a sitting today with studios offering portrait sessions in these unique processes. We very recently got in touch with a bunch of these old school photography studios to find out how they are standing out from their modern counterparts. You’ve most likely read about that here. However, we also wanted to share with our readers our full interview with each of these studios to paint a clearer picture of their visions, how they work, and what it’s like running their unique spaces.

Getting in touch with Markus Mahla of 20×24 Studio Berlin to tell us about their unique studio certainly gave us some of the most fascinating and detailed insights on the highly specialized art of 20×24 instant photography. Not everyday do we see instant photography at this scale, let alone the equipment used for it. We bet that it’s the first time for a good number of our readers to learn that something of this grandeur and historical relevance still exists to this day, and we’re glad that Markus could tell us all about it.

Phoblographer: Please introduce your amazing studio to us. When was it founded? Why did you decide to open a studio specializing in large format instant photography?

Markus Mahla: 20×24 Studio Berlin is a one-of-a-kind place that brings one of the most unique cameras of the last century back to life: the 20×24 Polaroid Land Camera. Polaroid built only five of these cameras in the 1970s. At our new location in the heart of Berlin, we present the beautiful number 5. It is the only operating 20×24 Land Camera outside the US. Number 2 is with John Reuter in NYC, and Number 3 is with Elsa Dorfman in Boston Area. What we do is pretty special: we produce mega format instant photography.

“I observed over the past years (and I was part of digital transitions in several companies with large and strong brands) that the more ‘digital’ young folks get or are, the more they are also very much interested in analogue experiences, such as taking a Polaroid picture. A process that you can touch, feel, smell, see, hear.”

The founding of our studio was a quite interesting journey. I registered a company just recently in Berlin Charlottenburg but the full story started way back. I was part of the Polaroid family for about a decade. In my later career – I think at that time I was part of the Boston team responsible for commercial photography – I met with Florian “Doc” Kaps at a Photokina. He introduced to us his idea to sell aged and matured film. To many in my company, it seemed to be stupid idea but it was the foundation of a great business – and what was unsalable once, the expired film became Doc’s business and his first company name.

Later after Polaroid went Chapter 11, I was the General Manager in the Central Region. Polaroid introduced the exit of Instant Film. At that time we where selling LCD TV’s and other tech stuff. It was a turbulent time. When the company led by Tom Petters filed for bankruptcy, Doc was maybe the only one who believed in Polaroid film. The rest is history. What I do remember during this journey – I was in different management roles in other companies, and Doc left the company he founded with the Impossible Project – is that the dream of a Polaroid fine art project never died. Later, when I joined his new project Supersense as a quiet investor, they got a Wisner Model in Vienna and did some 20×24 beautiful photography, mainly with the Chocolate film.

From time to time, Doc spoke to Jan Hnizdo, the owner of the 20×24 Camera, based in Prague if he’s interested to sell. Jan was my former boss, and I learned a lot from him about photography. Working for the Polaroid Collection was one of the greatest jobs I ever had. Jan knew that there is a high interest to get the real 20×24 Land Camera whenever Jan should decide to retire. Then it suddenly happened by surprise: Jan was in Vienna, shooting at Westlicht with Julian Schnabel. We had the typical once in a lifetime opportunity: leading the 20×24 project into its next 50 years. Otherwise, the camera may have disappeared through an auction.

At that same moment, I was just about to leave my current management role for a new opportunity. So, I didn’t think twice and raised the necessary funds to buy the camera. But the key condition was not the price; Jan wanted to have the right photographer in place. Only after Jan was convinced that we have the right successor was he willing to sell the camera to us in order to hand it over to its next mission. It was the sum of a number of very rare small coincidences that led us to this point. But the decision was quite easy and without a doubt I knew that this was the right time to start another analogue adventure: a 20×24 Studio in Berlin, in an environment that talks much about Internet of Things (IoT) and digitization, on a mission to support fine art photography in both analogue and instant.

Phoblographer: Can you tell us about the age group/demographics of your clientele? Why do you think they became particularly interested in large format instant photography?

Mahla: Although we are in a niche market I realized that we have a widely spread age group and target relatively different demographics. To me, the most exiting group is driven by the love and passion of young people for instant photography. I am convinced that this is a result of the general mega trend “analog”, but it was also driven by the Impossible Project. I observed over the past years (and I was part of digital transitions in several companies with large and strong brands) that the more ‘digital’ young folks get or are, the more they are also very much interested in analogue experiences, such as taking a Polaroid picture. A process that you can touch, feel, smell, see, hear.

The other demographic is older; they know Polaroid from their past and are excited about the 20×24 format for several reasons: they did not know that this exists (although they used Polaroid before 2000); they are surprised that it still exists or is “back again” or; they know 20×24 but simply had never any chance to see or have access to a 20×24 camera and they are all super excited that it’s now available and working in an international creative melting pot that Berlin is.

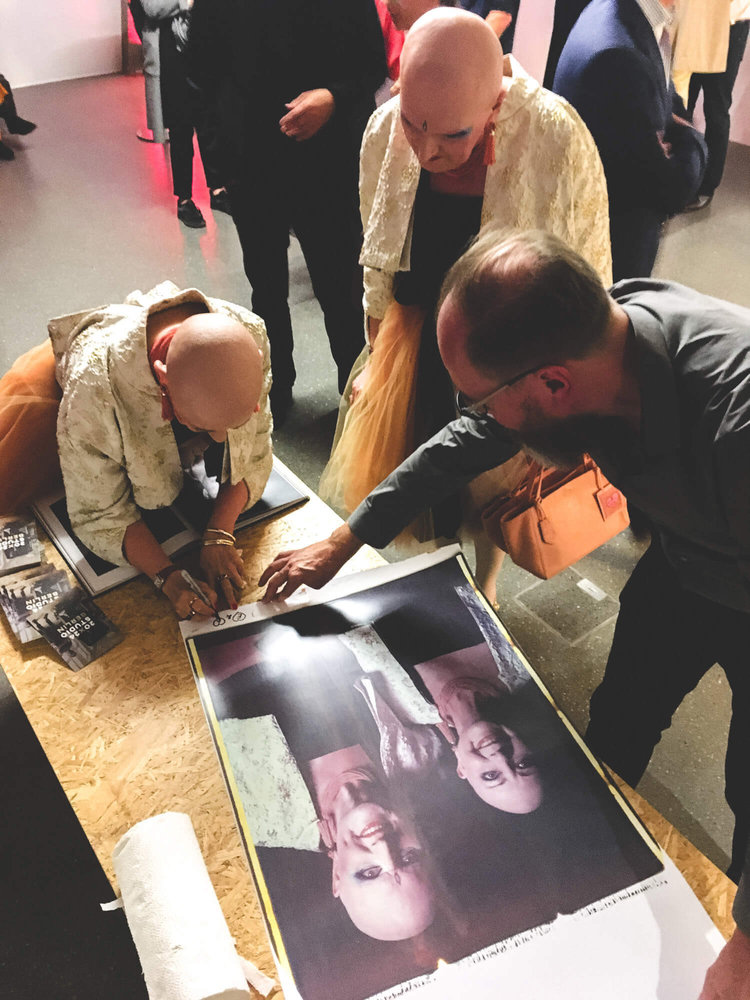

What all groups, clients and partners have in common is that they adore what we do. The 20×24 inch size is simply overwhelming; it gives you goosebumps and makes you overjoyed. I have never seen anybody who was not blissfully happy about his image and people who watch and follow the photography process are enthusiastic. This process was and is magic and attracts everyone in its spell. Taking a single photograph is an event in itself but, peeling this huge image apart in front of an audience, literally a minute after pulling it out of the huge camera, is a ball. People are moaning, applauding, screaming, they get goosebumps – we had folks who were in tears when their portrait was peeled off. It’s always a very special moment. Even me being around this wonderful peace of art for quite a while, I’m getting excited while I tell all this to you.

Phoblographer: What do you believe to be the most stand-out advantage/selling point of old school studios like yours today?

Mahla: I don’t feel this an old school studio. Albeit I like the term “old school”, it is somewhat a description of real, handcrafted manufacturing. Why do I believe this is so important? You may know the term “’Analog’ is the new ‘Organic’”; it is the title of a book by author Andre Wilkens. In an almost fully digitized world, people have a great demand for real analogue experiences. Supersense in Vienna is a great example and they were ahead of the curve. The analogue wave is getting larger and larger. Meanwhile, it is much more than just a mega trend. With this opportunity I was convinced it’s about time to extend the journey that my friend Doc started years ago with an extension in Berlin, focused on photography for now. With the jobs Oliver and I have done in the past couple of months and with the feedback we received, it seems we are on the right track. There’s more to come.

Phoblographer: What is it like putting together a large format studio and running it? What are the challenges and how do you overcome it?

Mahla: It’s been an adventure. The first challenge for me was I’m not a professional photographer so I needed to partner with a photographer who is a passionate portrait photographer and an artist himself, and also capable to be a simple operator of this unique system if the job or client requires. This is a rare talent. I was able to observe and learn this from Jan over the years when I was a student. Depending on the client, you either provide a full service or you are only an operator. If an artist or a professional photographer books the camera it’s key to be capable to step back and operate the camera while artist is running the creative process and trusts that the operator assists him to get the right results.

Oliver Blohm is one of these unique breeds. He can do both with a lightness as I have rarely experienced it. It was Doc who met him earlier here in Berlin and he introduced us, and we became friends fast and when the big day came (when Jan Hnizdo intended to sell his baby). Oliver was around for a training by Jan and later by John Reuter who visited us in Berlin. What a rush.

While searching for an operator for my camera, another aspect that came up was that the photographer should be able to bridge the analogue and digital world. I’m glad that Oliver is a designer and as a professional and art photographer, he can do both analogue and digital. Analog and digital are not mutually exclusive – in a way they represent two sides of the same coin. The more important side, the front side, is analogue. Soon we will offer also an opportunity to make a 20×24 photo from digital.

The other challenge we had to overcome was the physical challenge: the camera is huge! You need four full grown men to lift it. We had to consider that while looking for a studio. Luckily Oliver got us a place in the “KPM Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur Berlin”. Elevator is key. Getting the giant camera to clients like Bentley in Crowe, meeting guys like Bernie Ecclestone at this car collection, or artist Erwin Wurm in his castle for “One Minute Sculptures” requires different planning and logistics. You need a small truck to get camera, film, and equipment around. You need to take care of temperature, not only for the camera, but also for the precious and rare film materials. Some of them are so rare that we only have a very few rolls left. Gold dust as we used to say.

Location can also be a surprise. We found Sixt as a partner; they understood what we do and what we require. The other day when we were shooting with large lions near London it started raining – not at all easy for an “ancient” wooden camera. We peeled the film apart in the truck to avoid rain drops on the fresh image surface. Also, finding an insurance wasn’t easy. It is a very rare system – not easy to explain to banks or investors.

The last one is actually a major challenge and is a key task for this upcoming journey: we need investors who support us in developing new film. We have the engineers and friends at hand the develop film but if we do not find investors, this wonderful material might disappear from planet earth. For good. This would be a disaster.

Phoblographer: Can you share with us the most unique project you’ve done to date, and the story behind it?

Mahla: Most recently we were invited by the Big Cat Sanctuary though our friends from OPUS UK. Being there was exciting – you feel like you’re in Africa. But shooting large lions outdoors through a full day and being so close to them was stunning – and a bit scary. I don’t think this was done before. Major task was to make a full-grown male lion stand still. It took us quite a while and kilos of chicken to get him to the sweet spot, not to blink… we had so much fun although it was really frightening. Then, halfway through when we got a few reasonable shots of the lions, the World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Wladimir Klitschko showed up and we photographed him in front of the lion – what a day. Then, we went on to Crewe to shoot all first cars in Bentley’s long history at their headquarters the next day. Great trip – happy clients.

Wherever we go, the 20×24 Land Camera is an eye-catcher. People are super excited – it feels to me that they are even more excited compared to the past since this is such an unexpected surprise. The wooden camera and the way we operate looks like were from a Jules Verne novel. Hardly anybody can actually believe that something like this really exists in our digital world. It is spectacular.

Phoblographer: What is the most common misconception about this type of traditional photography that you try to dispel with your clients?

Mahla: The most common misconception is caused by a basic misunderstanding of the quality of the Polaroid material. Edwin Land built the 20×24 Camera to present the stunning quality of the film to his shareholders while introducing 8×10. The 20×24 image size could not only present the outstanding quality of the film but also bridge between instant mass photography and fine art photography. Edwin Land once said, “The aesthetic purpose of the new camera is to make available a new medium of expression to those who have an artistic interest in the world around them.” So, in a way it was always about art.

While I was working at Polaroid, I was also responsible for archiving the International Polaroid Collection and its transition to the Musee Europeenne de la Photo. Aside from what was in the US and Musee d’Elisee in Lausanne, this was the largest part of the collection outside the US. This was maybe one of the finest selections of artistic photography that I have ever seen and ran through my hands. Each photo is an original. Meanwhile, I am still puzzled to see – even when I visited Paris Photo few months ago – that Polaroids are still rarely offered, only a few galleries present large names mainly from the 1960s to 1980s, but little to no young contemporary photo art on Polaroid. Photography prints drive the Art Photography market. In my opinion there is a gap. This can be a massive opportunity for collectors and galleries, but more than that also for young analogue artists who just discover instant photography. We all have to change that perception.

Collecting Polaroid means you carry an image with longest lasting quality and an undoubted uniqueness. 20×24 images is the elite material. I bet in less than 10 years from now, people will acknowledge that this peel-apart image is the “oil painting” of photography. Polaroid art will raise in value dramatically over the next years. You could see first signs over the past years in the art market. But this is just the very beginning.

Phoblographer: How do you think this specialized form of photography will fare or evolve, say, in the next 10 years?

Mahla: To ensure that we with lead this “specialized form of photography” over the next 10, 20 or 50 years, the biggest step will be to fund the development and production of new films. This is maybe the largest challenge and it will drive the base for the evolution of this unique photography for many more decades. As mentioned, I strongly believe that in a world that is digital the demand for analog will grow further, not as an anti-trend but as a natural balance.

Analog will not get out of fashion. A digital device remains to deliver a stimulation for just two senses: hearing and seeing. We are still far away for “digital” to become a tool to satisfy any of the other three much more important senses: touching, smelling and tasting. It is a bit like any other analog to digital transition.

Analogue and digital can complement each other side by side. People love streaming music yet they still buy vinyl records. People take billions of photos with their smartphones but still sales of companies like Polaroid Originals and Fuji Instax are drivers of the photo industry. 20×24 photography will always be a high value niche, the prints remain rare and precious. I will stay very keen to watch and witness how this art will develop between analogue and digital and how artists may play this advantage over the next years in between those worlds. This is also an invitation for young contemporary artists. The story has just begun.