The next time you need a one-of-a-kind portrait, consider turning to one of these old school photography studios.

There’s no doubt that photography has gone a long way, from the equipment down to the techniques, and even the purpose of each shot. However, we haven’t really forgotten about the craft’s humble beginnings. If the fact that film is still very much alive surprises many today, imagine the astonishment once they learn that even more archaic photographic techniques are still being practiced. Wet collodion photography is as old school as it gets, and there are still a good number of studios out there that offer the unique experience and result it brings.

“The biggest challenge has been to learn all the ‘warning signs’ that the chemistry will throw up when things are about to go off the rails…”

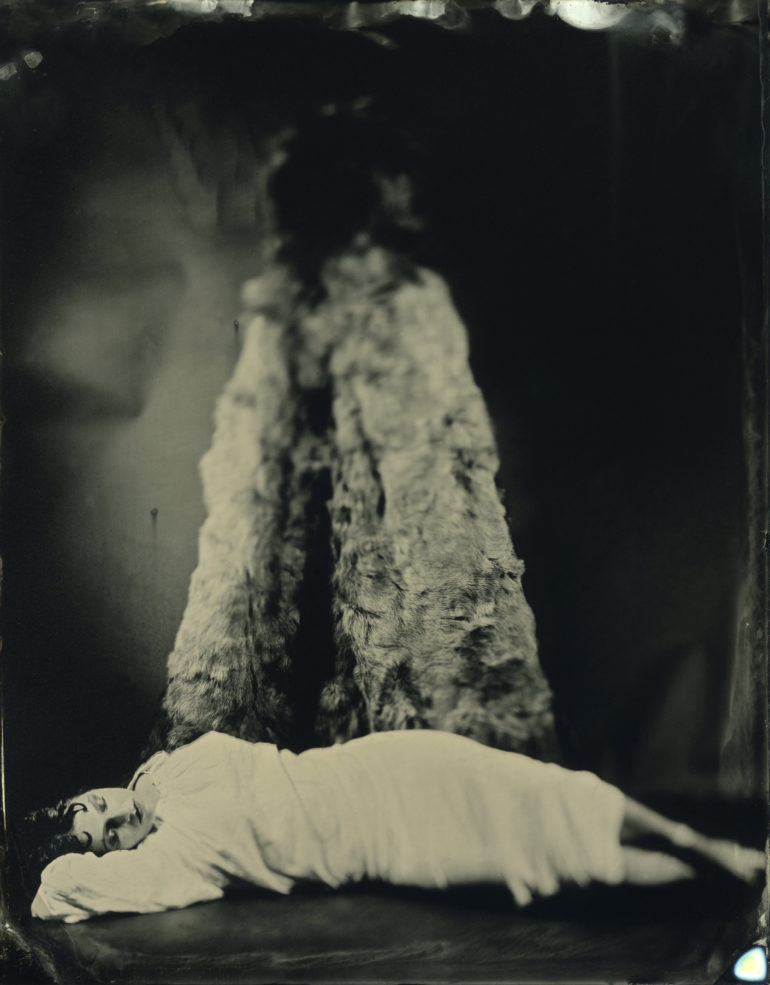

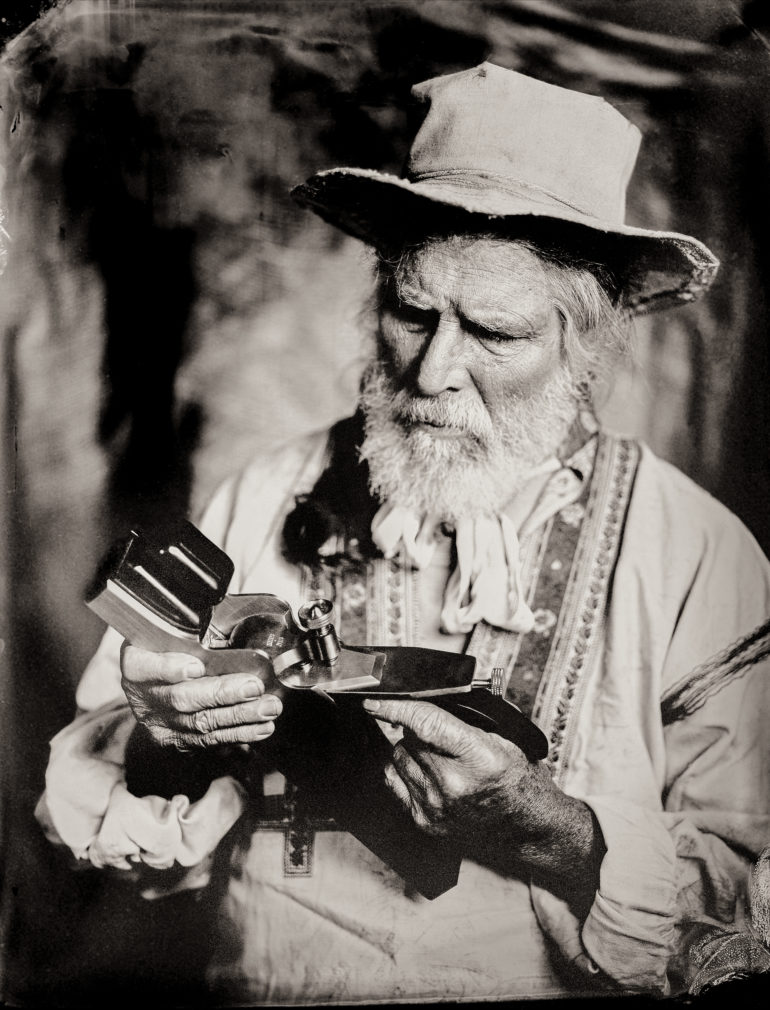

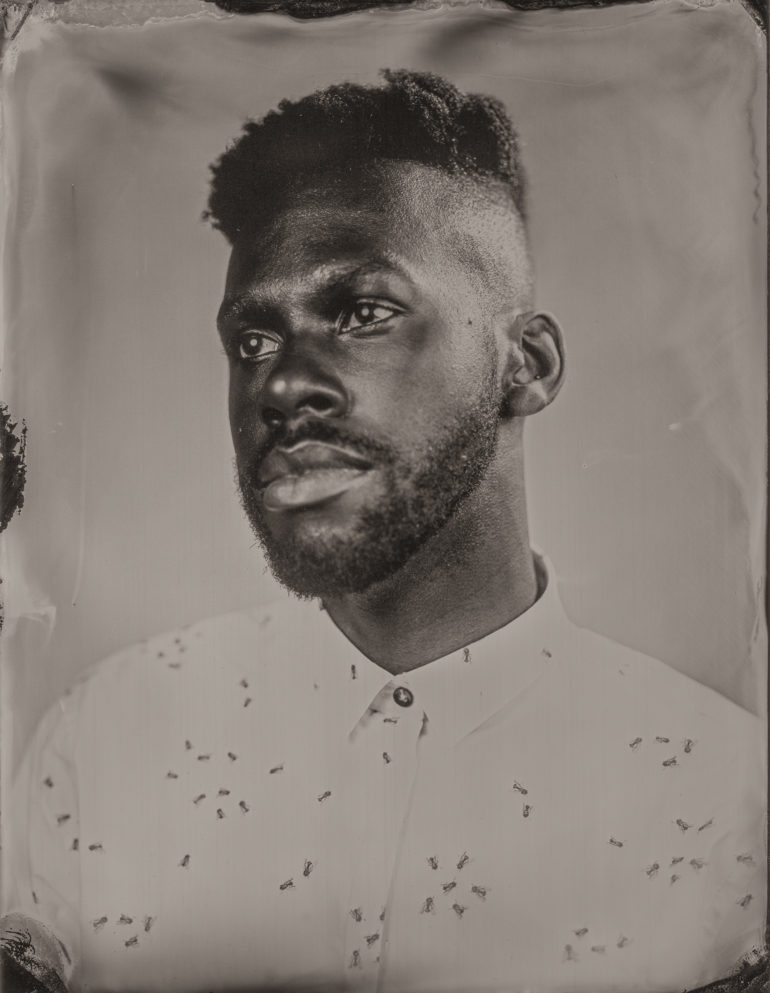

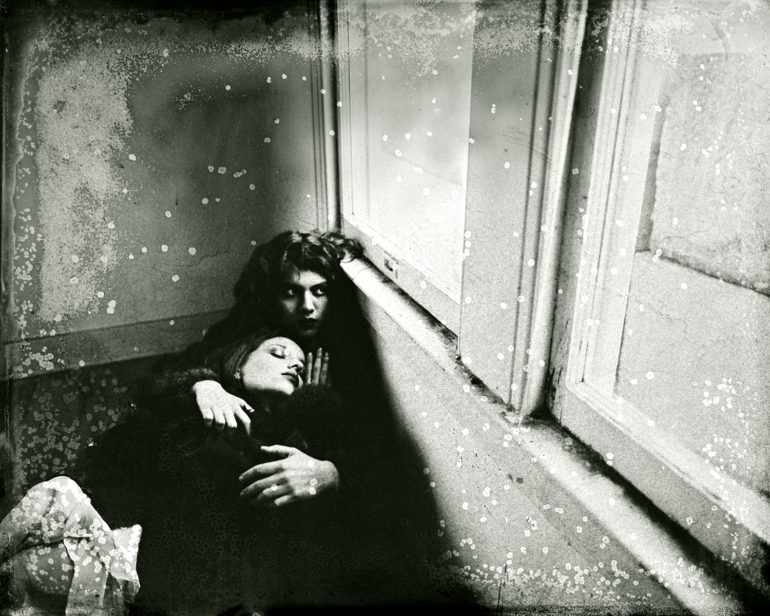

These old school photography studios are bastions of an era when photography was deemed magical in all its slow, meticulous, and tedious chemical process. It involves coating, sensitizing, exposing, and developing a photographic material, and often long exposure times. At the end of a session, you have a physical, one-of-a-kind image imprinted on either a glass plate (ambrotype) or a metal plate (tintype). Today, it’s mostly used for fine art photography projects, but these studios also extend the craft to anyone curious about how it works and how it looks.

These studios may not be the first to come to mind for many looking to get their portraits taken. But it’s the very unorthodox nature and antiquated look of the wet collodion process that allow them to stand out from the modern studios of today. We got in touch with some of these studios — mostly doing tintype photography — from all over the US and other parts of the world to give us an idea on their edge, their clientele, and why they think the craft will continue to enjoy the resurgence for the coming years.

Inspired by the Magic of History and Tradition

In the summer of 2010, four friends on a camping trip in Northern Ontario decided to work together on a project that would revisit a chapter in the history of photography. It eventually morphed into The Tintype Studio, born out of a vision for a collective revisiting the craft. “We enjoy sharing our work through exhibitions and workshops, and also offer a portrait service that enables the public a chance to take home a unique piece of history,” said Paul and Greg, who are currently running the studio. “Our group of four has since evolved to just the two of us, but it’s still going strong nearly a decade later.”

Oregon-based Alchemy Tintype has a similar story. In 2016, three close friends began a collaboration as a traveling and “pop-up” wet plate collodion (tintype) studio in Portland. They chose the name “Alchemy Tintype” because of the perfectly suited definition of taking a mundane metal and using chemical processes to make it precious. “In our case, taking aluminum plates and making beautiful images with elemental silver deposits; the highlights in wet plate are made of elemental silver,” said Ashley Jennings, who has taken over the studio for the last year. “I have been amazed at the response and support I’ve felt from all kinds of folks who respond on an emotional level to such a special historical process. There is truly something magical about it!”

“In our case, taking aluminum plates and making beautiful images with elemental silver deposits; the highlights in wet plate are made of elemental silver.”

Kari Orvik opened her own tintype studio in 2014, after shooting for Photobooth SF, a tintype studio and camera shop that both owners, Michael Shindler and Vince Donovan, decided to close earlier that same year. She had also taken a tintype workshop with Michael back in 2006 at Rayko Photo Center. In both of those communities she found a shared passion for keeping analog photography alive at a time when digital equipment was increasingly dominating the medium. “I had always wanted to open a portrait studio — I first started setting up mobile studios when I was working in affordable housing,” she said. “Now, specializing in tintypes has allowed me to stay in the darkroom and continue to meet such a diverse spectrum of people who share an interest in this process.”

Fine art photographer Adrian Whipp founded Lumiere, a traveling portrait studio, in 2013, largely in response to the demand that had built up around his hobby of shooting tintype portraits. “It seemed like a good time to open a tintype studio — digital photography was well established and had completely disrupted the industry. I felt that a gap had opened up in the market, and that people were looking for tangible, archival portraiture again.”

Apart from these tintype studios, there are also studios that can take your portraits in large format instant photos. Among these are SUPERSENSE in Vienna, which celebrates the old Viennese tradition of high-value portrait photography through 8×10 and 20×24 instant portraits. They also collaborate with 20×24 Studio in Berlin, which has one of five 20×24 Polaroid Land Cameras that were built in the 1970s. Markus Mahla, the owner and Managing Director of the studio, was once part of the Polaroid family for about a decade, and later met Florian “Doc” Kaps at a Photokina event. While Polaroid announced the exit of instant film and eventually filed for bankruptcy, Doc was the only one who believed in Polaroid film. The rest, as they say, is history.

“What I do remember during this journey…is that the dream of a Polaroid Fine Art project never died…”

“What I do remember during this journey – I was in different management roles in other companies and Doc left the company he founded with the Impossible Project – is that the dream of a Polaroid Fine Art project never died. Later, when I joined his new Project ‘Supersense’ as a quiet investor they got a Wisner Model in Vienna and did some 20×24 beautiful photography, mainly with Chocolate film.”

Then, after a series of several rare coincidences, Mahla was able to buy a 20×24 Polaroid Land Camera from his former boss Jan Hnizdo in Prague. “The decision was quite easy and without a doubt I knew that this was the right time to start another analogue adventure: a 20×24 Studio in Berlin, in an environment that talks much about Internet of Things and digitization, on a mission to support fine art photography in analog and instant.”

Setting Up and Running an Old School Studio

Make no mistake — a studio dedicated to traditional photography comes with its own challenges. It is, as described by Paul and Greg of The Tintype Studio, labor-intensive as nothing is automated. There are no do-overs. Small collectives also have to wear many hats to overcome such challenges. For Orvik and Whipp, who run their own studios, it’s also important to keep an open mind, stay calm, and pay close attention when ironing out the kinks of working with such an unwieldy and demanding process.

“The biggest challenge has been to learn all the ‘warning signs’ that the chemistry will throw up when things are about to go off the rails,” Whipp added.

To get to their skill level, there’s definitely some training, classes, and mentorship involved, but you can definitely get started exploring books and video tutorials on the subject. According to Jennings, what will equip you with the necessary troubleshooting skills to keep a tintype studio going is practice.

“Challenges can arise in ways you don’t expect with other processes. For instance, wet plate collodion plates have an ISO of around 0.5, which means that on a bright sunny day in open shade you still may need up to a second of exposure time. Sometimes the limitations of the process can feel hard to overcome, but keep practicing and don’t give up!”

Mahla talks about a different set of challenges that he found as an owner of a large format instant photography studio. “First challenge for me was that I am not a professional photographer. So I needed to partner with a photographer who is: a) a passionate portrait photographer and an artist himself; and b) also capable of operating this unique system if the job or client requires. This is a rare talent. I was able to observe and learn this from Jan over the years when I was a student.

“Depending on the client, you either provide a full service or you are only an operator. If an artist or a professional photographer books the camera, it is key to be capable to step back and operate the camera while the artist is running the creative process, and trusts that the operator can assist him to get the right results.”

A Subversion to Today’s Throwaway Images

Almost as soon as the film photography resurgence came out, the curiosity for even slower and older photographic processes followed suit. The market of these old school studios may be niche and the demographics varied, but their sitters all want to bring home portraits with unique and moving stories behind them. Do we credit this interest with the novelty of the medium? For all these studios, it’s not as simple as that.

They all agree that the handcrafted, one-of-a-kind nature of each image comes as the main attraction, followed by the fact that its resolution is astounding considering the age of the technology. How it sees light, the entire process of capturing and developing the plates, and the uniqueness of the archival results, and the fact that you get a physical keepsake — all of these draw appreciation and awe from the sitters with each session.

“People seem to get drawn into looking at a tintype photograph for far longer than they would an image on a screen. There’s a hyper-real, yet other-worldly nature to each image,” Whipp explains. “I think people appreciate the process of being photographed with such an old technique — it’s slow and cumbersome, and requires a certain focus from the sitter that can make for some really intense portraiture.”

“We are inundated with quick, forgettable, ‘filler’ imagery every day of our lives…”

From his experience with SUPERSENSE alone, Mahla also found that while everything is almost fully digital today, people seek “old school” because it describes something real, handcrafted, and organic. “In an almost fully digitized world, people have a great demand for real analogue experiences. I observed over the past years (and I was part of digital transitions in several companies with large and strong brands) that the more ‘digital’ young folks get or are, the more they are also very much interested in analogue experiences, such as taking a Polaroid picture. A process that you can touch, feel, smell, see, hear.”

As Jennings also eloquently put, it sells precisely because it’s not quick, cheap, or easy — a total opposite of today’s often throwaway photography culture.

“We are inundated with quick, forgettable, ‘filler’ imagery every day of our lives. We scroll quickly through images of our friends and families, and even the really important photos can get lost in the mix when presented on social media. Tintype’s resurgence now, I believe, is a direct response to and subversion of that idea. Each plate takes several minutes to made, and each plate is a one-of-a-kind physical object; there is no negative or file to fall back on in case you accidentally put a thumbnail through the emulsion and ruin the plate.”

(Really) Old School Photography in the Next 10 Years

So, tintypes and large format photography have been steadily gaining traction in the past couple of years. What about in the next decade? We ask our studio people for their fearless forecasts, and their answers are all pretty interesting.

While the process may not have a lot of innovation left, Whipp remains hopeful that more people will be curious enough to learn the process themselves and open their own studios.

For the folks of The Tintype Studio, the archivability of the images, and the simplicity and effectivity of the “recipe” make the wet collodion process special and interesting today, and in the years to come. “We believe that the bounds of the process will continue to be pushed further, as image-makers apply current and future technologies with their own unique creativity.”

Jennings, on the other hand sees wet collodion photography evolving in incredible ways, and cited an example of one such innovation. “One wet plate photographer recently made a drone into a tintype camera, for instance!”

However, she also notes that social media will also be a key player in how traditional photography will prosper in the future, ironic as that sounds. “It’s easier than ever to discover new artists, processes, and opportunities. And although I make tintypes as a respite from the bustle of the Internet, the Internet has allowed me to build a business around doing what I love! I expect that this trend will continue, and I hope it will encourage young people to take time to study the history of photography before they inevitably innovate new ways of photographing.”

As for large format instant photography, Mahla believes that the way to keep it going is to develop new film for it. “To ensure we with lead this ‘specialized form of photography’ over the next 10, 20, or 50 years, the biggest step will be to fund the development and production of new film. This is maybe the largest challenge and it will drive the base for the evolution of this unique photography for many more decades.”

For Orvik, wet collodion photography — and we can say it’s the same for all the other “old school” processes out there — will continue to thrive, not only with the number of photos made, but with the unique interaction it brings. “I think the importance of the interaction between photographer and subject will not go away, and the physical object of a photograph will continue to have meaning in an increasingly virtual world.”

Special thanks to the people behind the amazing old school studios for sharing their photos and insights to help shape this feature:

Paul and Greg of The Tintype Studio

Ashley Jennings of Alchemy Tintype

Adrian Whipp of Lumiere Studio

Kari Orvik of Kari Orvik Tintype Studio

Markus Mahla of 20×24 Studio Berlin