Last Updated on 08/21/2017 by Chris Gampat

This is a guest blog post by Ellis Vener. All images and text by ©Ellis Vener are being used with permission.

Being in the path of totality during a total solar eclipse is one of the very coolest, weirdest, and most benign natural phenomena you can ever experience. As the eclipse progresses through totality the air around you cools, natural sounds change, and during totality not only does the sun go dark except for the sun’s corona’ extending beyond the edge of the moon, but the light in the sky and on the land is like nothing else I have ever experienced. To say it is an awesome (a word which when used here means “extremely impressive and very different from anything else I have ever experienced”) experience is an understatement.

My First Total Solar Eclipse

I have only experienced totality once, and that was during a trip to central Mexico in July 1991 with a then-girlfriend and my good friend George O. Jackson, Jr. George is a photographer himself with deep Mexican roots and was working on a decades-long project documenting the indigenous tribes in Mexico. He planned the trip around the eclipse and picked the tiny village of Yolotepec, Hidalgo as the best place to be for expiring totality. Yolotepec is north of Mexico City and in the middle of the Mesquital desert and the dry summer weather would give us the best shot at a clear sky during the eclipse. During the week long trip I was introduced to pulque (a mildly alcoholic drink made from the fermented sap of the agave plant) and cabrito, visited a canyon near San Miguel de Regla where a waterfall cascaded over basalt columns, and visited a Catholic pilgrimage site. Another day was spent at Edward James’ Las Pozas. Las Pozas is surrealist architectural folly, sprawling across a jungled hillside. If you are ever in Mexico City for a week, schedule a two week trip to visit both Las Pozas and San Miguel de Regla.

Totality

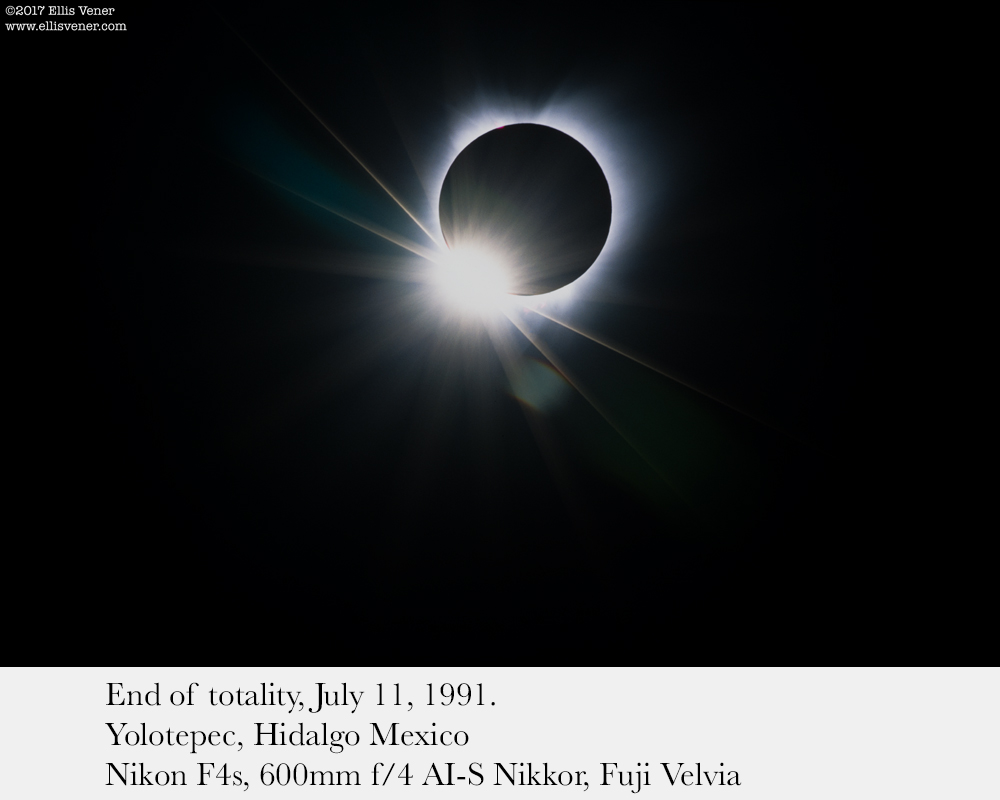

When viewing or photographing a total eclipse the most emotionally intense periods are the moments leading up to totality and the seconds as totality begins and ends with a dazzling burst of light as the tiniest fraction of the sun disappears and then reappears between mountains on the Moon’s horizon. Being in totality is a hugely weird and benign experience. It was the natural phenomena in the world around us that had the most profound effect on me. As the moon starts to move across the sun not only does it get unexpectedly darker but the air cools down too and if you are lucky enough not to be in a crowd you can hear changes in the natural soundscape as birds, animals and insects get ready for the false dusk. Another environmental change during totality is the way light changes in the sky above you and on the ground around you as the moon blocks direct light from the sun. Not only is there less light but it also has a silvery sheen to it. At the horizon you may see a pale tangerine glow which makes it seem as if dawn is happening all around you. As a photographer you’ll be busy making sure your gear is ready but do pay attention to what’s going on around you that makes your experience of the eclipse unique.

Hopefully you won’t be in a crowd. In the tiny Mexican village we set up in, except for the town’s lone barracho – we were the only humans out and I think this made the event more special. “Where were all of the people?” we wondered. As the sun’s light returned we found out as people started coming out of their houses that the government had warned people not to look at the sun during the eclipse and in this village that was apparently interpreted by the villagers as a warning they would go blind or die if they were outside during the eclipse.

Totality begins and ends with a dazzling burst of light – the diamond ring. Pointing a 600mm at the sun and moon during totality my exposures were around 1/60th at f/5.6 on Fujifilm’s Velvia Pro (ISO 50). But in the instant the diamond ring flashed, it jumped to 1/8000th and I think the frame where I capture the dazzle of the diamond ring is over exposed by more than a few stops.

My Gear

For the trip I brought along a 600mm /4 AI-S Nikkor and other Nikkor lenses ranging from 200mm down to a 16mm f2.8 full-frame fisheye. During the eclipse I used both the 600mm and the 16mm. The 600mm was on a Nikon F4s in Aperture priority mode and the 16mm was mounted on an F2. Fujifilm Velvia, an ISO 50 film, was my film of choice.

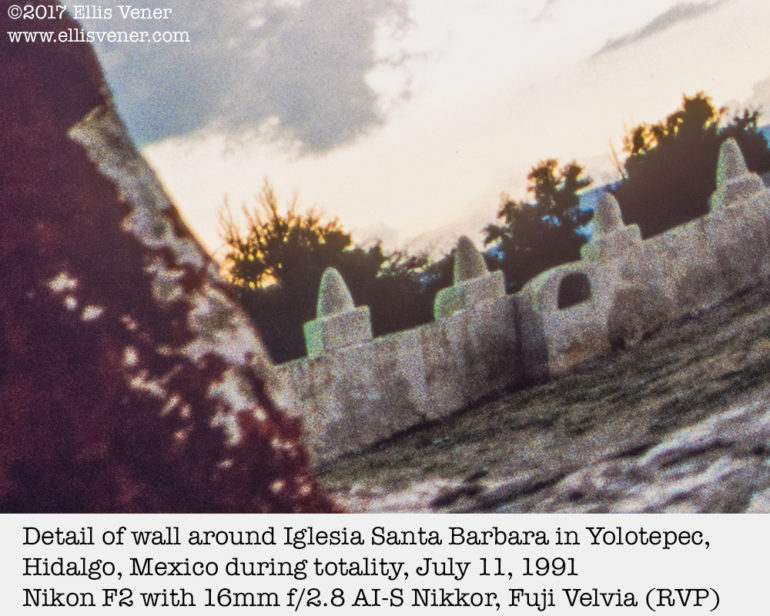

Along with the 600mm I shot with the 16mm to capture the eclipse in the context of the place we were in: the churchyard in front of Ygelisia Santa Barbara, a small Catholic Church. It’s hard to see in the blog-sized reduction accompanying this article but in the best of the photos I made with the 16mm lens the light from the eclipsed sun was so dim that even though it was near noon on a sunny high desert summer day, a green traffic light illuminated the decorative concrete fence surrounding the church. To get this composition I laid down on the ground at the base of the monument.

Plan ahead: Totality is brief – on the Oregon coast it will last a scant two minutes and at its longest will be only two minutes and forty seconds as totality crosses Missouri, Kentucky and Tennessee, and will be down to 150 seconds as the moon’s shadow crosses the South Carolina coast.

Along with the 600mm I also used the 16mm to capture the eclipse in the context of the place we stopped: the plaza in front of a Catholic Church (Ygelisia Santa Barbara). It’s hard to see in the blog sized reduction accompanying this article but in the best of the photos I made with the 16mm lens the light from the eclipsed sun was so dim even though it was the middle of the day on a sunny desert high desert afternoon, a green traffic light illuminates the decorative stone and concrete fence surrounding the church. To get this composition I lay down on the ground at the base of the monument to frame the shot this way.

The brief moments of totality – on the Oregon coast it will last a scant two minutes if you are on the western coast of Oregon and at its longest will be only two minutes and forty seconds in totality path across Missouri, Kentucky and Tennessee, by the time totality path crosses the coast of South Carolina the period of totality will be down to two minutes and thirty-five seconds.

Special Equipment

Besides a solar filter to protect your camera’s sensor, lots of media and fully charged batteries, you’ll also want a solid tripod and head combination and a cable release. If you are going to use a super telephoto lens or telescope to point the camera up at the sun a gimbal mount will make your life far easier, as will a tilting preview screen on your camera. I cannot emphasize enough that, except during the period of totality, unless you look forward to roasting your retina you should not look directly at the sun through your view finder. According to an NPR interview with Canadian Ophthalmology Professor Ralph Chou:

“When any part of the sun is uncovered and the eclipse is only partial, viewers need eye protection — even if there’s just a tiny crescent of sun left in the sky, Chou says.

“That crescent of sun is glowing every bit as brightly as it would on a day when there isn’t a solar eclipse,” he says. “The difference is that instead of leaving a round burn on the back of the eye, it will leave a crescent-shaped burn at the back of the eye.”

Don’t think it’s safe to take quick, surreptitious glances, he warns.

“Actually, those quick little glances do add up,” says Chou, “and they can, in fact, accumulate to the point where you do get damage at the back of the eye.”

He says the damage isn’t immediately apparent because the light-sensitive cells of the eye will keep working for hours after the injury before finally going kaput. Typically, people go home after an eclipse thinking everything is fine, says Chou. Then they wake up the next day and can’t see.

“Everything is really, really badly blurred right in the center of their vision,” he explains. “So they can’t read. They can’t see faces. They can’t see road signs.”

This kind of vision loss can get better over several months to a year. But about half the time, it’s permanent, says Chou.

Likewise, except during totality, using live view may roast your sensor.

If you are planning on photographing close-ups of the eclipse you will obviously need a long lens. On a full frame camera with a 600mm lens the sun/moon disc will cover about 1/4 of the frame and I recommend you use either a 400mm or 600mm lens if you shoot it with an APS-C camera. Once again: prior to and after totality use a solar filter when pointing the camera at the sun. It can be removed during totality BUT remember to put it back on about 30 seconds before totality is scheduled to end.

Other technical and technique notes

- Turn off auto ISO as well as autofocus.

- Bracket, but keep in mind that turning you’ll need to compensate for the dark (near black) sky that will take up much of the frame. So bracket more towards the negative side to keep the ring of light around the moon from over exposing.

- Use a cable release if you have one.

- Use live view especially if your camera has a tilting preview screen. Your neck will thank you afterwards.

- Shoot a lot.

- Try to make photographs that are specific to where you are and who you experience the eclipse with.

- Have fun. Total eclipses are one of the weirdest yet most benign natural events you will ever experience. Savor those few moments of totality and do not get so wrapped up in taking pictures that you ignore everything else. Live in the moment: use your ears as well as your eyes, and you will feel a definite temperature drop.

- One last thing: There will be literally millions of photos made of the eclipse itself. Many of those will be made by people who have a lot of experience photographing eclipses and use some special equipment to make spectacular images. Paying attention to your surroundings will give you have a chance to make your photos unique.

(For the path of totality and other relevant maps see Great American Eclipse.

Ellis Vener is a working photographer and has been since he was 16. Here’s some more information straight from Ellis himself.

I began my photography career in high school photographing concerts before getting a liberal arts degree at the University of Texas. I worked my way through college in the late 1970s shooting fraternity parties on weekends and after graduating, apprenticed for three years with a nationally known Houston based advertising photographer who specialized in very complex photo–illustration (in the pre-Photoshop years) work before opening my own studio in 1984. In 2002, I moved from Houston to Atlanta.

I photograph corporate annual reports, industrial and advertising work for a wide range of clients. Editorial clients include Texas Monthly, Newsweek, Forbes, Bunte, the Christian Science Monitor, the New York Times, and various institutional publications. Since 2003 I have been a contributing editor for Professional Photographer, the monthly publication of the Professional Photographers of America trade association, and other photography related publications. I also lead workshops and occasionally teach individual photographers.