Last Updated on 04/20/2015 by Chris Gampat

All images by Jack Baldwin. Used with permission

Jack Baldwin is a journalist by day, and uses digital cameras for his work. But he began his journey into film photography when he moved from Australia to California and purchased a medium format film camera. When he moved back to Australia, he started his journalism career, which was about getting the shot and filing as soon as possible. But with film, Jack found something more.

“I shoot film because it’s the antithesis of that. I can take my time, I don’t have to stress, it doesn’t have to be something that sits nicely next to a headline.” states Jack. “It’s just the photo I want to take.”

It eventually turned into him going to workshops and experimenting with many, many more formats. Jack tells us that it makes you think that much more about composition and framing.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

Jack: I picked it up when I was a university student, studying journalism. At the time I thought of it as another skill I could put on my resume that most of my peers didn’t have. Oh, and a way to break up the crippling theoretical monotony of my course – that too.

My first course was black and white film photography, which was great. I was in the darkroom with a bunch of Art students – all a lot more talented and creative than I was, if only because they were used to working visually. It was nice changing gears in to that mindset every week.

To begin with my photos were really average. Just a few months later I was making images pretty true to the vision I was chasing – not technically great, but satisfying for myself anyway. Having a project, a theme between photos was a nice way to work for me. Back then I wasn’t too well versed in photographers so I drew from literature instead – asking myself how can I capture the mood of a book like Heart of Darkness in a photo?

That was a short semester and I quickly moved to digital when I finished. I picked up a 5D Mk II, which I still use for work. I was lucky to have some very talented friends who’d teach me things in their spare time, and I still shot film every now and then with my mum’s old Canon Elan 7. It took EF lenses like my 5D so I could change between them easily.

I travel a lot and try to do something worthwhile while I’m away. In my final year I took off to Japan to basically do some real world journalism, I suppose you’d say. I followed a charity up to Fukushima, the nuclear and tsunami disaster zone. That was an experience. Just in general a fairly emotional and confronting situation to be in, even for a short time. A photo from that trip ended up being shown internationally in an exhibition, and I think that was when it was really locked in for me; that I was making some good things and that some good could come out of what I was making!

Phoblographer: What made you want to do analog work for an entire year?

Jack: The project was unintentional in a lot of ways. I was living in California for a year in 2013. Over there I picked up my first medium format camera and started shooting a lot more film. Being in a foreign place, even if it seems familiar to home, really opens up your shooting. I’m bad at taking photos back in Australia because I’m so used to it, I guess. It’s like when you’re driving on autopilot and only paying attention to the bare signals around you – if you’re driving on a new route you’re paying much more attention.

I ended up getting an internship at MILK Studios in Los Angeles for the last few months of my stay. That was a sort of creative realignment but not for any artistic reason. It was a pretty amazing environment to work in – really intense commercial photography. I was basically just helping to look after the gear and pack it up for shoots. But it completely cured me of Gear Acquisition Syndrome. The gear locker there is amazing, every lens or body or back you’ve ever lusted over, and they’d have five copies of each one. Once you’ve messed around with all these ten thousand dollar lenses or fifty thousand dollar backs, they lose that allure. I stopped chasing the latest gear and just focused on taking good, interesting photos.

I came back to Australia in early 2014 and started working as a journalist almost right away. It’s a good job and I’m always covering something different, which is great. Yet, when something becomes work, it can lose that allure as well. I take photos for work pretty often, all digital of course. Usually they’re shoots where either my me or my subject are really short on time, so it’s stressful.

I shoot film because it’s the antithesis of that. I can take my time, I don’t have to stress, it doesn’t have to be something that sits nicely next to a headline. It’s just the photo I want to take. That’s really how it all came about. I enjoy it and it keeps me interested.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you started this project.

Jack: As I said, it was largely unintentional. In fact, I only realised I’d been on a project the other day – I was looking back at some photos I’d taken through the year, some shots from my phone of the workshops I’d been to and places I’d taken my cameras, and I realised – hell, I’ve done a lot of new things this year. I decided to put it all together and throw it up on Reddit because the analog community there is great and I thought they’d be interested. In fact, there were parts I left out because I didn’t want to go on too long.

I tend to have a very short attention span. It’s a drawback in some ways but it also drives me to try new things. When I was shooting digital, I was trying new things every week, even if it was just sitting in the backyard doing astrophotography one night and then macro the next day. As long as I kept moving it kept my interest and, without realising, I was getting better at it.

“it completely cured me of GAS – Gear Acquisition Syndrome.”

By no means have I mastered my digital photography, but as far as what I can do with the camera, that’s all a known quantity to me now. I’ve spent years trying just about every technical type of photography there is, and its capabilities are pretty clear. Film and analog are different. Different bodies work in different ways. Different film reacts differently and different formats really challenge your thinking. That keeps me going now.

Phoblographer: Many photographers often feel that when they come out of projects like this, they’ve really grown as an artist and a photographer. How do you think you’ve progressed?

Jack: I’ve come a long way in the last year, without a doubt. I think working with different formats forces you to think a lot about your framing. If you’re used to shooting a square frame on medium format, and then you spend time with a panoramic frame, you’re forced to re-evaluate that square frame when you come back to it.

The photos that have come out of my camera in the last year have definitely been the most ‘artistic’ I’ve taken so far, I’d say. I’m satisfied with quite a lot of them, which is interesting because the first thing I usually see when I look at my photos is what I can do better. I also think I’m beginning to understand what people say when they talk about a photographer’s wit, that kind of visual flair or language that conveys a message through a picture, a sort of cleverness in framing.

Technically I’ve gotten better with all my cameras and shooting, which happens naturally over time. That’s perhaps not the most valuable thing by itself, but it really does remove a barrier between you and creating something artistic. Once you stop wrestling with knobs and settings and gear, you can have a clear line of vision from the present moment to the final print.

I’ve also gotten better at working for the shot I want, though that has probably come about through work. In the past I’ve skipped certain photos because I was too shy or too lazy to take them. At work, if I don’t take a photo because I’m shy, I miss it. If I don’t work with my subjects or ask people to do what I need, I don’t get the shot. That’s carried over, for sure.

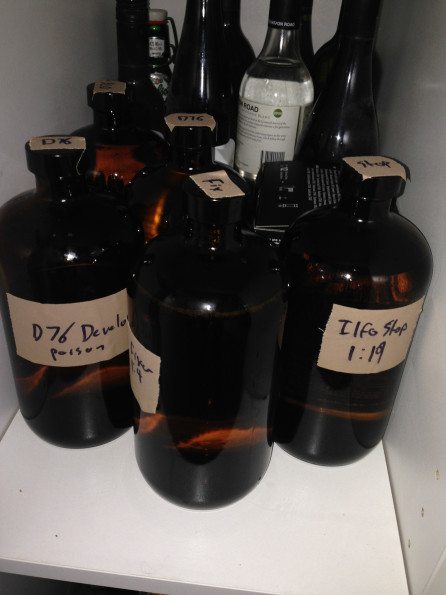

Finally, with the developing, processing and scanning of my own film, I’ve definitely become more aware of the manual labour involved in a shot. So I try not to rush things when I don’t have to – because I’m just making more work for myself down the line. I now have a pipeline where I take a photo and handle it all the way through, which is great.

Phoblographer: What formats did you shoot with and have the most fun with?

Jack: 8mm movie film. I’ve dabbled in this but still haven’t shot enough to develop a roll. It’s good fun, and I like shooting movies, but I’m usually after a degree of visual fidelity with my photos that really small formats struggle with. I’m not after lomo shots and light leaks!

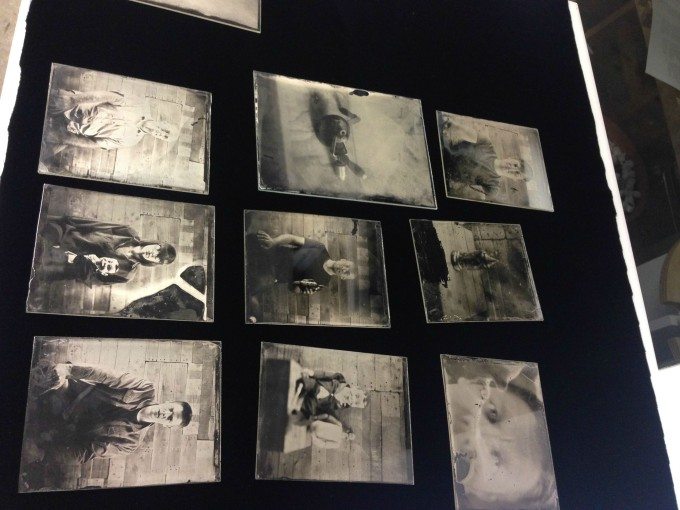

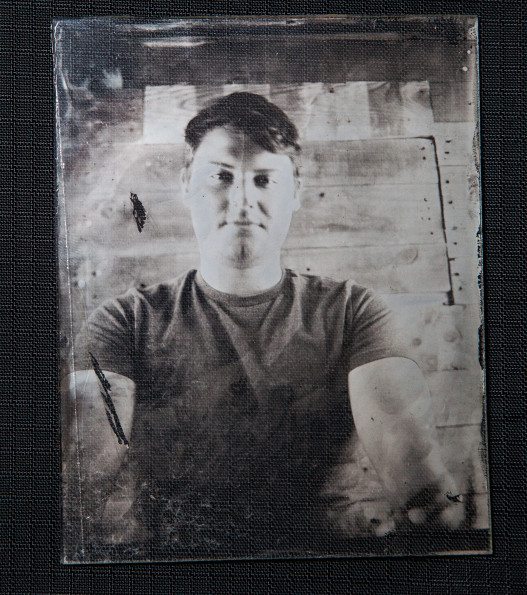

Wet plate collodion: This is technically a large format style of photography, but working with plates is very different from film. In this case it’s about as analog as you can get. You take a step further back from film, because you’re making the emulsion yourself and pouring it on to the frame yourself. Luckily the glass plates were already cut for me. This was a day long workshop at a local art coworking space, The Analogue Lab. Those guys are awesome and certainly a big element in my year of shooting film.

I’m not the handiest of people, so I did a pretty shit job with a lot of my plates and made some mistakes. The immediacy of what you’re doing adds an element of stress to it. You only have a few minutes to take a frame and develop it before it loses its light sensitivity. The results are great though. I wouldn’t mind doing more of it, but it’s certainly one of the more technically daunting formats to use.

4×5 large format film: I got hold of a Horseman 45FA shortly after doing my wet plate course. It’s a lovely, compact large format camera, even though that sounds like a contradiction. A lens can fold inside of the body which is rare for field cameras, and it’s built like a tank. I changed the bellows and repaired the body to put it in good working order, and now it’s smooth as butter.

Large format film is certainly something else. The size of a piece of film is ridiculous. Shooting is certainly slower than the smaller formats. Every shot I took started with setting up the tripod, getting the ground glass in focus and then loading the film holder. Even loading film in the first place is a task. For me, large format is the ultimate road trip format. It’s great fun pulling up in your car, throwing the camera over your shoulder and hiking up a mountain or across a cliff to get a photo. You certainly think more about your shots than with any other format. I don’t really want to go larger though – 8×10 is getting a bit silly in my mind.

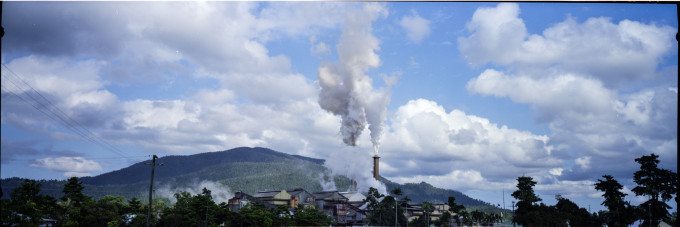

6×17 panoramic photos: I got my large format camera with panoramic shots in mind. You can get an extending back which takes medium format roll film, doing photos in 6×17 format – roughly 3:1 aspect ratio. I’ve always loved that format, probably from the old cinema epics like Lawrence of Arabia. It gives almost any photo that cinematic feel to it. Technically, the back is a pain in the arse because it adds even more steps to shooting than typical large format.

It’s worth the pain though. There’s nothing like a 6×17 negative. You only get four shots per roll, so they better be good. I think with that type of framing you start looking for lines – it naturally suits long, flowing lines. A horizon, a beach curving around a bay, the edge of a forest. It really draws the eye along and makes for interesting photos. It also cuts out a lot of the rubbish around those lines – it’s probably my favourite, most precise format in truth. You get really focused images if you get it right. Just make sure you have a spirit level, because if your horizon is off, your whole image is screwed. Once again, I think it hits a sweet spot – you can go for 6×24 but that’s a bit much.

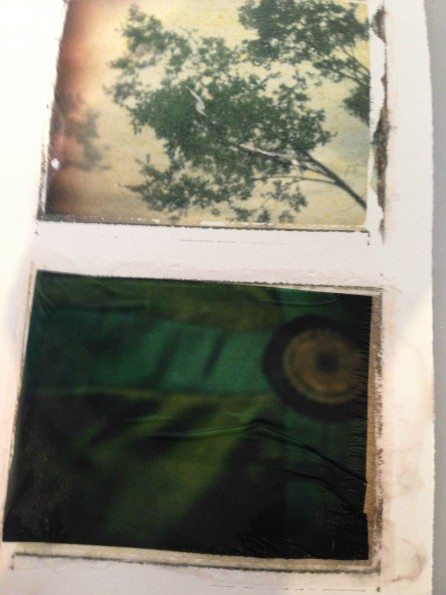

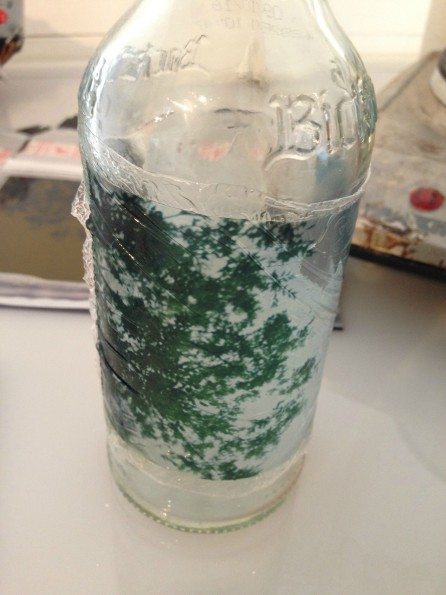

Polaroid in all of its forms: This was great. Another workshop at the Analogue Lab, this time focusing on the alternative uses for polaroids. I had some in the fridge already, and a polaroid back for my Hasselblad, but that’s not great since it only uses a small portion of the frame. There are so many uses that I had no idea about. You can ‘print’ a polaroid on to paper by pressing a freshly developed photo against it, which makes for an interesting image. You can get a negative out of the disposable side of a polaroid by pouring bleach over it, essentially (so many I’d thrown away without knowing!). You can gently simmer the polaroid in water and the layer of emulsion will lift off, letting you stick it on paper or whatever gelatin will stick to. That was really interesting, because all of a sudden your photo is a physical object, this thing you can manipulate with your hands. I have loads of boxes of polaroids in the fridge now – I think the next step is to get a back for my large format camera which can handle them.

Medium format: I’d already shot quite a bit of medium format before this last year, when I was in the US and around, but I feel like I really started to nail the square format of my Hasselblad. This was by far my most used film type and camera over the year. It’s the sweet spot between quality and convenience, I think. Great for picking up and taking out the door.

I went to Germany for a few weeks in February of this year and only packed my Hasselblad with me. I didn’t want to be distracted by digital or slowed down by lugging my tripod and large format. It ended up being a great choice, and a really interesting experience. You focus all of your thought and energy in to one format and I think the end results are much better for it. The square shots to me are almost like looking through a window in to the world, where panoramic is like taking a slice out of an image. Framing in such a tight format is really important, trying to get the contrast I like to fit in there – fore and background, light and dark, all in a small space. I started shooting black and white again for the first time in a long time (apart from my initial foray in large format) and I’m all over it now, I love the drama that look gives.

Different film: I also shot a lot of alternative film in the last year. I used my first rolls of Aerochrome colour infrared film. They’d been sitting in my freezer waiting for a worthy subject, and I took two to Germany. I didn’t get great results out of either, but it’s a learning experience and I still have some left. I also used plenty of black and white infrared, which makes for some really interesting pictures.

Phoblographer: All in all, do you have any idea how much money this all cost you? Do you feel it was worth it?

Jack: A fair chunk of money, overall. The courses at the Analogue Lab can run anywhere from a hundred dollars to a few hundred, depending on the materials you use. It’s not cheap, but I feel it’s worth it. Things like wet plate photography are pretty hard to get started with on your own and with no one teaching you. The amount of labour involved just to get started in that, and the dedication required to work through mistakes is pretty astronomical, so it’s nice to get a slice of it.

My large format camera and panoramic back weren’t cheap, but the fact I got an old beat up one and did the repairs myself certainly helped. I probably paid a bit over a thousand Australian dollars for the camera, lens and repair materials, and a few hundred for the panoramic back, but it also adds a lot of capabilities to my kit. I buy as much as I can second hand, and a lot of film photographers, particularly the large format guys, take good care of their kit so it looks like new anyway.

Setting up my home developing and scanning wasn’t cheap either, but in the long run it will save me a lot of money and give me a lot more flexibility. Now it costs me less than $2 to develop a roll, I’d guess, not including the initial outlay of a few hundred dollars, but every roll I develop, the more that cost is absorbed.

I’ve certainly spent hundreds on film too. Luckily that’s the only cost you can’t recover. Good film gear tends to hold its value really well – so if I have a lens I don’t like, or I get sick of my panoramic back, I can always sell them and make my money back just about. Some of the more niche items take longer to clear, but that’s just the way it is.

Outside of boozing (that’s the Australian way) and travelling, most of my disposable income has gone to film. But I’m at the point where I’m happy with what I have, there’s not much more I need or can think of – which is good, because I should really start saving a bit more.

Phoblographer: What did shooting with analog cameras and processes teach you about your own creativity and getting new ideas?

Jack: I think that format is inextricably linked to what you make and perceive. By that, I mean that an image taken on a large format camera is going to have a very certain characteristic about it. If I had to set up a tripod to take a picture, that will look different to what I would take on my medium format handheld camera. If I’m shooting panoramas, I’m looking at a scene differently than what I would for a square shot. If I’m shooting infrared film, I’m hunting different light than on normal film.

It might not seem like a big thing at first, but you end up having this huge breadth of experience to draw on. It makes things so much more interesting. Just like I humoured my short attention span by trying different techniques on my digital in the early days, like macro or astro or portraits – I tend to leap between formats and it always keeps my mind ticking along.

Some of the historical formats are great too, things like the wet plate photography. They broaden your horizons of the photographic process – how things had to be done, how they can be done. There are great old photographers like Felice Beato who everyone should look at. The fact he was dragging a donkey-led cart filled with glass plates in to warzones and taking photos like that and developing them on the spot certainly make my excuses for not lugging a large format around look pretty weak.

I think that analog’s biggest advantage is that it’s all there, it’s all laid out. There’s nothing to chase or get swept up in other than what you want. The greatest film cameras ever made have already been made. The best lens for a film camera is already for sale. You don’t end up chasing gear for gear’s sake – you don’t want a lens or a body because you’ll get a sharper image, you’ll get it because it allows you to take a different photo, to make a different statement. And I think looking for those differences and experimenting with them can result in some great stuff. There’s plenty that analog and analog photography can teach primarily digital photographers too. It’s not just Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier-Bresson. A little research and time opens up a whole new world.

Phoblographer: If you had a chance to do this project all over again, what would you do differently?

Jack: Not much, to be honest. I had a great year, went to a lot of places and did a lot of things. If anything, I wish I’d started a lot of this stuff earlier. I wish I’d been developing at home before this, and I wish I’d gotten back in the dark room earlier. Going through that entire process from shooting to printing makes it a lot more rewarding and tangible. I’d like to use my large format and panoramic camera more too – I might start packing it on the way to work each day and see what I see.