When the time comes that 35mm film or the sensor format just isn’t cutting it anymore, consider medium format. Though the film can surely be costly, it is also still capable of delivering some beautiful results are comparable and many times better than full frame 35mm DSLRs.

On the other hand, you could just be looking for something else to give a try.

Format

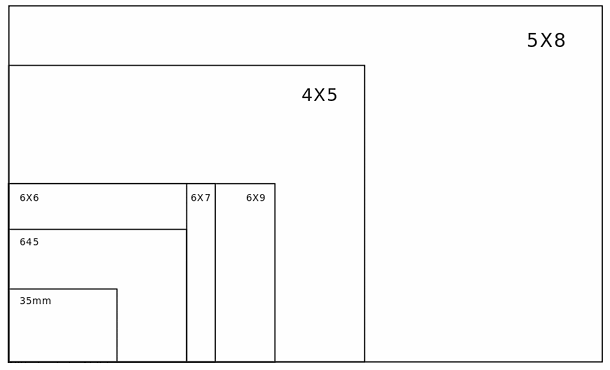

First off, when it comes to working with medium format film, you should know that when it comes to talking about negative film that requires development, you’ll primarily be dealing with three major formats and sizes. Granted, there are other sizes available, but these three are the most widely accepted and talked about when it comes to medium format film.

6×4.5

This format is most commonly referred to as the 645 format; but the proper designation is 6×4.5. This is the closest to the standard view and format of 35mm film that you can really get to. As medium format progressed, the 645 format is what survived to continue on into the digital world. When you hear names like Pentax 645 or Mamiya 645RZ, know that this is the format that we’re talking about.

These types of cameras are the more traditional ones that you’re used to seeing with a mirror, prism, lens, and film back. More on this later.

6×6

Love Instagram? Then you’ll love the 6×6 format. The 6×6 format produces, you guessed it, square images. When doing this you need to consider a whole new multitude of factors. First off, you’re not working with a rectangle anymore and instead your entire scene is in the square format.

What this essentially means is that you need to work with the format and new rules of composition to make your images that more compelling. However, the square format has a natural balance to it that many photographers and creative directors simply love to begin with.

6×7

Of the three most common formats, the 6×7 format is the least common, but offers users the largest negative space to capture scenes with. By all means though, the 6×7 format returns 120 film back to the rectangle. What most folks used 6×7 for though was landscape shooting. With the negative area being so long, the depth of field at a given aperture was (and still is) quite slim.

And just for reference, here’s a nice chart for you.

Something else that you should also know about medium format film is that you more or less have a reverse crop factor when it comes to 35mm film. When you go from 35mm to APS-C, you go down in size. But from 35mm to 120, you go up in size. What this results in is an 80mm medium format lens being more of a normal approximate 50mm perspective. With that said, what it also means is that at a given focal length you will get much less distortion.

Want a great portrait lens? Then the equivalent of your tried and true 85mm f1.4 lens for your full frame 35mm DSLR will need a 120mm f2.4 in full frame 645 format. While that sentence may be a bit confusing to you, consider the fact that when medium format camera systems use the term full frame, they are often talking about it in terms of their own 645 system, and not a 35mm system that is the colloquialism.

You’ll also need to stop down a lot more in order to get anything in focus. If you were used to shooting your subjects at f4, you’ll need to be at around f8 to get the equivalent depth of field. That conversely means a slower shutter speed or the need to add more light to a scene.

Film Types

Just like in the 35mm world, there are two main types of film: positive and negative. It’s a lot easier to work with these types in the medium format world and for the most part, they’re also the ones that still remain in use today.

Positive

While most folks talk up negative film like it’s the best thing that they’ve ever shot on, positive film can also deliver some spectacular results if you have the right settings. For the most part though, it’s tough to come by. The most accepted products were Fujifilm’s 100C and 3000B.

However, 3000B was recently discontinued though you may still be able to find some stock of it somewhere. On the other hand, 100C is still in production and is usually sold in the 3×4 size. Providing that it isn’t expired, the film is very beautiful when the right light and the right lenses are used. We strongly recommend using it with a proper medium format SLR vs a Polaroid Land Camera as those lenses sometimes cause flaring issues that are very tough to work with.

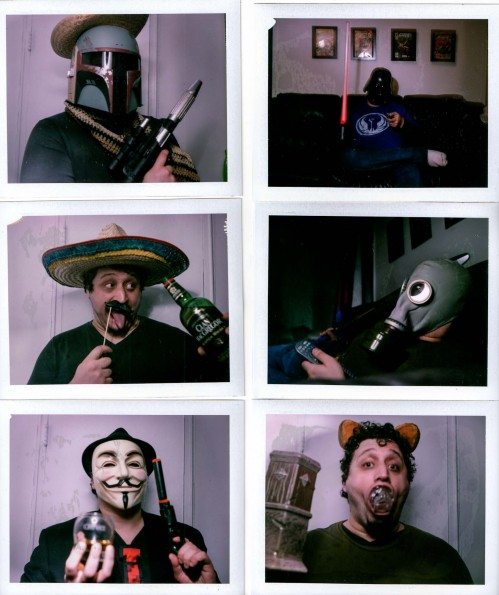

But don’t take our word for it–we’re just a bunch of semi-traditionalists that prefer to have the best colors possible. And in reality the marketplace loves the look of Polaroids. Bring in Polaroids to an art buyer or a gallery then add some direct flash and you’ll be in full business. While that statement is partially over exaggerated, it is also partially true.

If you’re not able to get your hands on any of that Fujifilm stuff and instead have another Polaroid camera, the Impossible Project will become your friend very quickly.

Negative

Then when it comes to working with negative film, you can be glad that there are still more options around but may not be around for a long time. And just like with positive film, negative film comes in either black and white or color. Some of our favorites are:

– Kodak Portra 400: best for portrait work and skin tones

– Kodak Tri-X 400: great for street photography

– Kodak Ektar 100: excellent for landscapes

– Fujifilm Velvia 25: you can’t beat this for landscapes

– Ilford Delta 400: our personal favorite for street photography and anything needing gritty looks

– Lomography Lomochrome Purple: a relatively new film that transforms greens into purples.

Gear

When it comes to medium format gear, you’re essentially broken down into two areas: rangefinders and typical SLR cameras. And each system has their pros and cons.

SLR Cameras

This isn’t your typical 35mm SLR system at all. In fact, there is a lot more to it. Your basic medium format SLR comprises four pieces:

– Medium format back: to hold the film. These can have dark slides inserted so that you can shoot with one roll in one back and another roll in the other back. This way, you can literally, switch out a roll of film mid shoot.

– The lens: obviously one of the most important parts of the camera.

– The body: the body is the central area with the mirror and probably electronic contacts

– The Prism: this can either come as a top down experience, or it can be a proper prism with/without electronic contacts and metering.

After all of this you can attach certain things like a grip for the bottom of the camera; a side grip which can be automatic, single stroke or double stroke; or straps and bellows systems. It all depends on how the manufacturer decided to make the system.

The other big camera type are TLRs: which are twin lens reflex cameras and require you to look down into them and focus. They can be quite difficult to work with.

Rangefinders

Medium format rangefinders are very much considered to be the creme-de-la-creme of many photographers. Pictured above is the venerable Mamiya 6 rangefinder, which has some amazing lenses. But if you talk to any medium format photographer about something like the Mamiya 7 II, they’ll immediately swoon.

Not only are the lenses great, but the system is lightweight, fairly small, and perhaps the quietest camera ever made. But man are they expensive.

With rangefinders, you lose the ability to swap out backs and also don’t see the depth of field in the viewfinder–just like most other rangefinder cameras.

Brands

Though we aren’t ones to particularly start a brand war, there are totally some brands that have major advantages over the others.

Hasselblad: usually considered by most to be the ultimate top of the line. Indeed, many of their cameras are well built machines that will outlast your lifespan.

They’re just really, really pricey.

Bronica: Perhaps one of the best bang for your buck alternatives, but the problem is that you’re also stick with medium format film–which sucks really badly if you want to go digital one day.

If you have no problems with film, then you’ll enjoy these systems. They’re built very tough too. Considering that Tamron used to manufacture these, we’re not surprised.

Mamiya: Also a very great choice for many photographers. They have loads and loads of cameras, systems, and lenses. So just make sure you do all your research.

Kiev: This was a Russian company that tried to mimic Hasselblad, and they did a really great job. Though Kiev’s cameras are quirky, they’re capable of delivering some really jaw dropping results.

Yashica: Known mostly for their TLRs, Yashicas are affordable and have a beautiful lo-fi quality about them. You’ll enjoy them for sure.