It’s easy for photographers of a certain age to romanticize the ideals of those like Garry Winogrand or Bresson. Others instead might stray towards the questionably cult-like cliques formed by photographers like Eric Kim or Thorsten Overgaard. But famous street photographers know that this is a long game — and that it’s not just about making it on social media. They take this idea with them holistically through their journey onto the streets to capture their images worthy of being a blockbuster for their career.

All images in this article are used with permission by the photographers in our interviews.

Not every photographer goes out to shoot the most candid moments they can find. Street photography works in a very similar way to cinematic stories. The images are either character-driven or story-driven. You might have heard Bruce Gilden speak about characters while Joel Meyerowitz would try to tell a story instead. They’re two different approaches, and they formulate different stories.

Table of Contents

Intense Focus and The Hunt

“Early on, I was often crippled by shyness when deciding whether to bring the camera to my eye,” says Melissa O’Shaughnessy to us in an interview. “As time went on, I overcame my fears by realizing that I wanted the picture more than I feared the consequences of taking it.” Conquering fear is a big part of being a street photographer. Finding a way to do it will often yield you some of the best photos, as she’s demonstrated. This mentality is prevalent with many street photographers. But Melissa also finds a way to do her subjects justice in the photos she takes. For example, the theme of the strong woman was big in her book Perfect Strangers.

Some photographers go out to shoot with a very specific thing in mind. But others, like photographer Dimpy Bhalotia, try to react as quickly as they can when they encounter a scene. In a previous interview with her, Dimpy told us that develop a sense of unconsciously moving with the subject. “You have to be very quick and invisible in the streets,” she told us. “To capture something natural, your subject shouldn’t know someone is watching them. You have to merge yourself in the crowd.” Dimpy likes capturing movement as it happens.

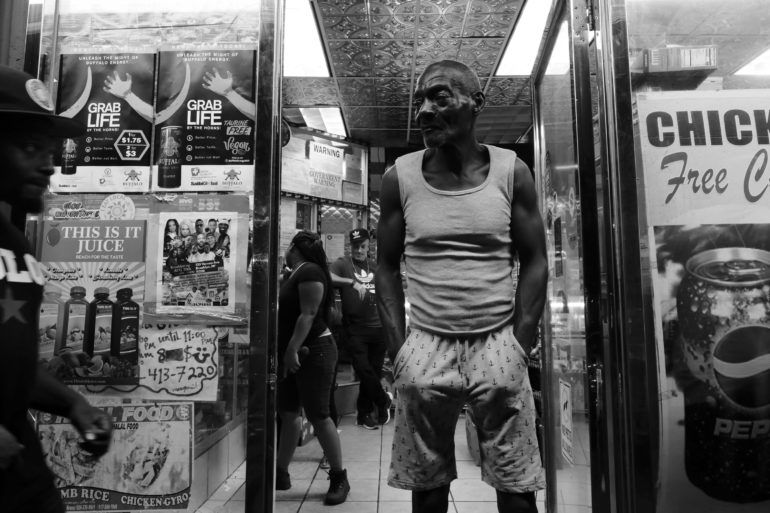

Looking at one of Dimpy’s images provided to us in our previous interview, we can notice several things. Firstly, she’s focusing on shooting only in black and white. This not only immediately draws the eyes to specific things in the scene, but it simplifies the photo to the human brain. Dimpy is also using natural light to figure out how shadows will affect a scene. As is evident in the scene above, she used reflections to tell a larger story within a small frame. All this, combined with specific framing and understanding of the culture around her, all work out well for her.

In fact, Dimpy tells us that she goes to a place and tries to understand the people and the culture before getting more into photographing what’s in front of her. This is a common tactic used by some of the best photojournalists as it helps people get used to the fact that a camera is in front of them. But Dimpy tries to more or less be a fly on the wall instead.

I remember I was in Copenhagen and I kept thinking to myself, the sky looks slightly lower towards the earth compared to other latitudes and longitudes I have been to. Maybe it was my imagination but I tell you that being sensitive to nature and understanding it makes a huge difference when you are doing street photography. The shades of gray and the scale of birds make a huge difference. It gives me goosebumps.

Dimpy Bhalotia

The idea of being the fly on the wall isn’t really a new one. If we analyze Paul Kessler’s “Q-Train” photo, which is the lead image of this article, we can notice many things that make it appealing across so many different fields of study. Just focusing on the idea of color theory, we can see various layers working in the scene. Steve McCurry tries to focus on three colors within a portrait to keep it simple. Though we can say that this is maybe more of a candid portrait, Kessel finds a way to make multiple layers of colors work and have them uniquely all stand out from one another.

More importantly than just the colors, there’s the candid moment. We are told multiple things about this portrait:

- Who: It’s about a mother being overwhelmed by her children

- What: The moment here is very relatable to several adults because they’ve either had children or they’ve had to endure hearing the results of someone else’s breeding.

- When: This is a relatively recent photo. But it’s something that can stand the test of time.

- Where: We’re in the NYC subway on public transportation. Many tourists and residents alike experience random moments on the subway.

- How: Paul simply took the photo when he noticed what was happening. Paul told us that he estimated the distance and got the shot.

- Why: This photo is so appealing to us because it’s holistically a beautiful moment around motherhood while also demonstrating strength within the chaos that is life and the NYC subway system.

Similar things can be said of many of Paul’s other pieces. His photos often show some sort of connection between people and work to tell a story within a larger frame. In cinema, it’s often said that New York can be a constant character in a movie. And clearly, we see that in many of Paul’s other images, such as the one above. Provided to us in our previous interview, the image shows how a family can find solace and peace while trying to get around public transportation. It’s a stark contrast to Paul’s other photo we previously discussed.

What’s evident in the work of both Dimpy and Paul is that they’re constantly looking around, gauging light, and being in tune with their environment. They’re probably both often taking breaks because it requires very deep concentration and understanding of what’s going on in front of them. More importantly, the photographer needs to connect their technical and artistic sides. Most photographers understand that this translation process can be very difficult.

Many photographers, such as Dina Alfasi, never want to be seen. They feel like when they’re seen, they break the candid moment because people become aware that they’re being photographed. To that end, Dina has the perfect tool: her iPhone. After starting out with an old-school Kodak Instamatic camera, she knew that it was the perfect tool for her to take the candid images she cares about capturing.

Her process is a simple one: going to work on the train and noticing things as they happen. Dina pay attention to the light, shadows, and most importantly the human moments happening.

“All the portraits I shoot, taken without the knowledge of the subjects,” she told us. “These photographs could not happen if they were aware of the camera. Even after shooting, I don’t inform my subjects because I use the train every day, and if people are mindful of this, I’m no longer will be able to photograph those spontaneous moments.” Dina focuses on the emotions of the moment first and foremost. She has her own creative vision, but she also is receptive to exactly what’s happening in front of her. And by looking through her photos, we’re presented with simply beautiful moments that are bound to warm our hearts if we’re open to it.

Getting to Know the Community

Though photographers like Dimpy Bhalotia try to get to know the community in a more introverted way, several other photographers go ahead and gain their trust first before conducting the street photography that they do. Photographers like the legendary Jamel Shabazz have been doing this for decades. He’s built long-lasting relationships within the communities in New York City and even shares stories about the people he’s photographed on his social media pages. One can tell that he truly cares about the people he’s shooting. His character-driven stories are part of what makes his photos so appealing.

“What I discovered early on as a photographer was that person who is dressed fashionably tend to be more open to being photographed,” Jamel told us previously. It’s important to note that not all of Jamel’s images are character-driven — he surely has his share of story-driven candid photos. But what’s sometimes controversial to street photographers is the approach of getting to know people beforehand as it breaks the candid moment. However, Jamel’s images continue to show real people in public. The images are sometimes posed, but they showcase the unique personalities of people.

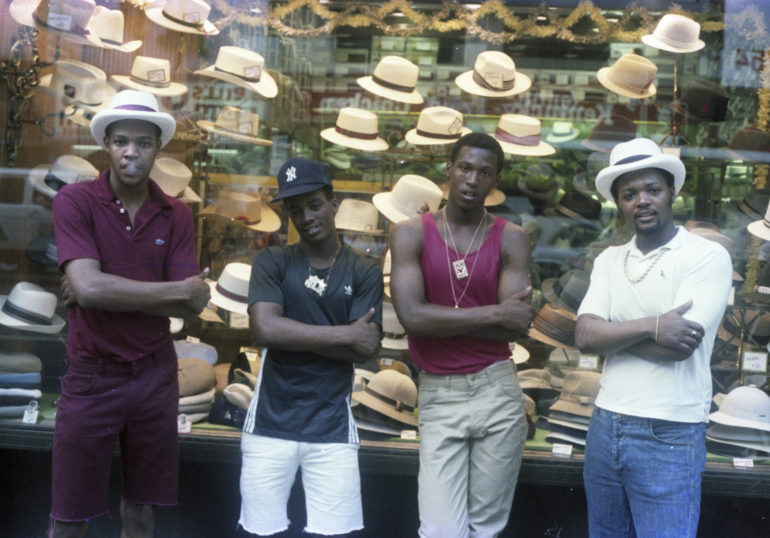

In the image above, Jamel told us about how these men all specialized in shooting Polaroids of people. His quote to us tells a lot about how he works:

I knew these Brothers very well, prior to taking this image. They were all fellow photographers, who specialized in Polaroid photography and made their money photographing folks oftentimes in a regal-looking wicker seat (known as a peacock chair) against a wide range of portable backdrops in the heart of Times Square. Their fee was $3.00 for one framed 4 x 6 print, or 2 for $5.00. The young man on the far right, Shabey (pronounced Sha-bey,) was a master of the craft and is responsible for photographing thousands of folks during much of the 1980s in and around 42nd Street. My brief conversation with them was rooted in photography, as they took a break from taking pictures. Seeing that three of the four of them had hats on, I knew that the hat store would serve as the perfect backdrop. This photo was made on the corner of 42nd Street and 7th Avenue and they are instinctively posed the same way, as they are all members of the same conscious fraternity. During the 1990s, this location went through major renovations, transforming the majority of the landscape. Gone are the adult stores and sleazy theaters, replaced with more family and tourist-friendly establishments. In comparison, today’s Times Square looks more like Disneyland.

Our takeaway here is that Jamel finds ways to focus on the who, when, when, where, how, and why — which is a huge part of photojournalism and, therefore, a big part of certain styles of street photography. Jamel tells the story to us but also makes us realize different things about the people in the photograph. If this were shot today, one can easily wonder if the gentlemen in the image should’ve been holding their cameras to create a more environmental-style portrait. Regardless, Jamel gained the trust of these men to get a photo like this.

This tactic is very important, as we can tell in stories by folks like Xyza Cruz Bacani. She works to get to know the people she photographs. Arguably, Xyza is more of a photojournalist than a street photographer — but he work is sometimes done in public, and so she’s considered to be a street photographer in many circles. Xyza has told us that she’s still in touch with most of the people she photographs — which is similar to what we find with Jamel.

In the photo above, Xyza is striving to tell the story of migrant workers protesting for their rights. ““For them to share their life with me and allow me to share it with the world, that makes them all compelling. I’m super lucky and grateful for their generosity,” she said to us. Xyza refers to many of the people in her photos as almost like family — which isn’t really seen or said by lots of other photographers. As such, she has a completely different take on the photos she presents.

An approach like this is done by other photographers, too, such as Jens Krauer. Krauer, who faced wrongful scrutiny for his project documenting the people of Bed-Stuy, worked to get to know the subjects he photographed. “Whenever I am given the trust the work demands, I am very careful to not abuse it or to create any negative consequences for the subject,” Jens told us. “This process can take hours, days, or months and even then, there is no security in getting a good image that speaks for the story. Insecurity if things happened and if I am being misunderstood are with me all the time, and my method of dealing with this is to be completely open at all points along the way, towards myself and the subjects.” Jens could easily teach a masterclass to many other modern street photographers on the work that he’s done. His images feel so natural because the people have this must trust in him and what he’s doing.

Street photographer Concha De La Rosa works to get to know her subjects but in a completely different way. Her approach is perhaps the most fascinating one and could help to reassure many shy photographers. Instead of getting to know people beforehand, Concha takes their photo and then starts a conversation with them. With all this in mind, she cares intently about how the people are presented in her work. “…moments where I think I may have captured a really intimate moment— I talk to them,” she tells us. “If they don’t have an email, I will ask them where they go usually for coffee, just so I can bring them a print or a pen drive with the picture on it for their relatives.” Concha can do this for several reasons — including having nearly two decades of experience and confidence. However, she often has a creative vision in mind and upon shooting the frame, isn’t shy about ensuring that the person has a copy of the photograph.

All these photographers have work that juxtaposes the photographs of homeless people on the streets that we otherwise see on Instagram under the #streetphotography hashtag. To that end, they take a more photojournalistic approach that isn’t necessarily seen by others. While they’re all recording human life as it is, photojournalists on a payroll often work with their subjects to tell their stories.

The Art of the Photo Wait

Though most street photographers tend to think about working as quick as possible to get a candid frame, a few others have a different approach. There’s the idea of the photo wait, which photographer Jonathan Higbee specializes in. As he walks around cities, he tries to find clean backgrounds, irony, the right light, etc. It may mean that Jonathan looks at the light hitting a scene and sits around, waiting for someone or something to walk into it in just the right way.

Some folks talk about this as “working the scene.” And it truly is a similar thought process. This has helped his work to stand out from so many other photographers. Combined with the work he’s on social media and with other publications, he’s inspired so many others to pick up the camera.

Other photographers also feel similarly. “The best advice I can offer is the same thing I have to remind myself every time I go out to shoot,” says photographer Michael Young to us in an interview. “Slow down and pay attention to what’s going on all around you. Look at the light, the environment, the scene, the people, and the interactions.” to Michael, the more aware you are, the better you can anticipate when something is about to happen.

All of these photographers have completely different approaches to their street photography. But at the end of it all, no one method is better than the other necessarily. Some may have both viewers and other photographers questioning their ethics. However, none of these photographers are arguably causing public harm or destroying someone’s reputation. And in public, a photographer typically has the right to do whatever they want.

What matters, in the end, is the result. More importantly, appealing to various human emotions and eliciting a response is what matters in the art form. Art, after all, is supposed to make people feel something.