“You were proud of your heritage but had little understanding of its whole meaning and significance,” says photographer and visual artist Melanie Issaka of what it was like to grow up as an African in the UK 20 years ago. She spoke in great detail about the roadblocks and frustrations many POC artists have to endure even today. What irks her the most is being asked to adjust her work to fit more with what an audience wants — rather than express it wholeheartedly for what it is.

POC and female artists and photographers are underrepresented in today’s art world. And in the pressure to get their name in lights or kickstart their careers, artists can often be pressured to revise or redo their work to fit in with someone else’s views or expectations. Over time, the artist produces bodies of work that are done more to get their work out there than actually being what they wanted to express. Melanie Issaka has often experienced these pressures but has always stood her ground.

It’s a slower process, and I enjoy shooting and making contact prints in the darkroom. Working with film can often be unpredictable and allows for elements of surprise.

Childhood In The UK

Growing up in the UK was challenging for her due to the lack of understanding back then of her cultural and racial significance. “My experience of studying history in school did not teach us this; black history began with Europeans discovering Africa and consisted of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the American civil rights movement,” says Melanie of the selective coverage of black history taught during her childhood. “There was no mention of African-born Roman emperors such as Lucius Septimius Severus, Clodius Albinus, Marcus Macrinus, and Aemilianus, Or the African Generals and soldiers who fought in the roman invasion of Britain.” she goes on to add.

We are repeatedly told the same stories of black history until they become the only narratives. Fragments of events become whole truths as prejudice and stereotypes turn black people into caricatures and spectacles

The Backstory to ‘Of Boys And Men’

As an only child with many cousins, Melanie Issaka was the only girl among six boys. They grew up together and attended the same school. She began to be fascinated by notions of masculinity. The gender differences between them and the various spaces they were allowed to be in becoming more apparent to her.

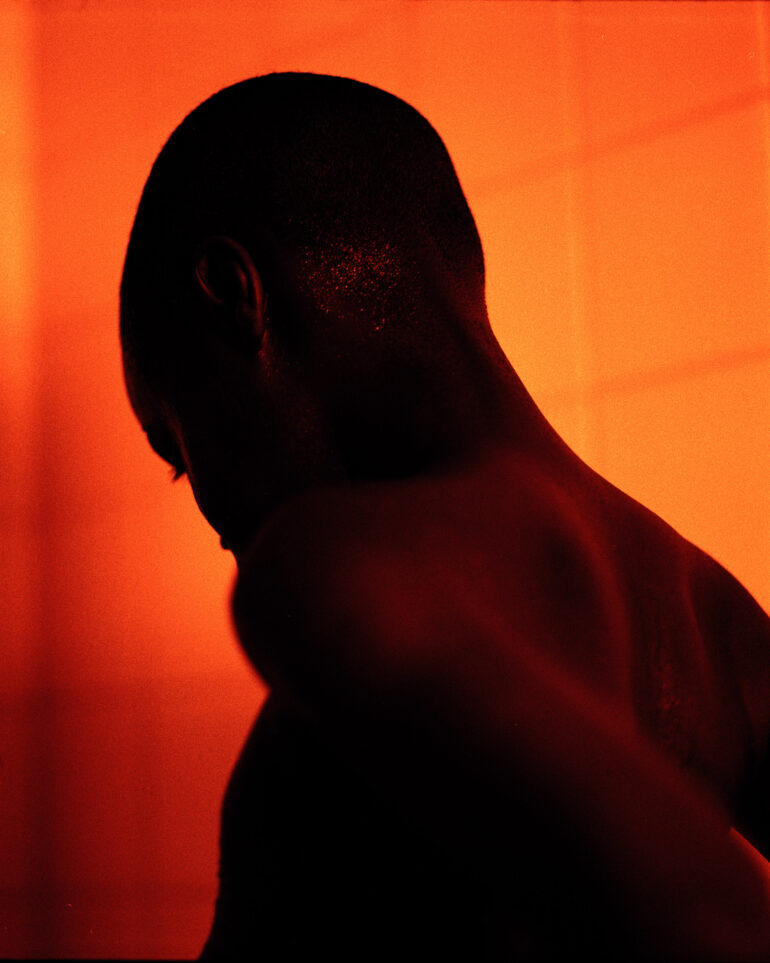

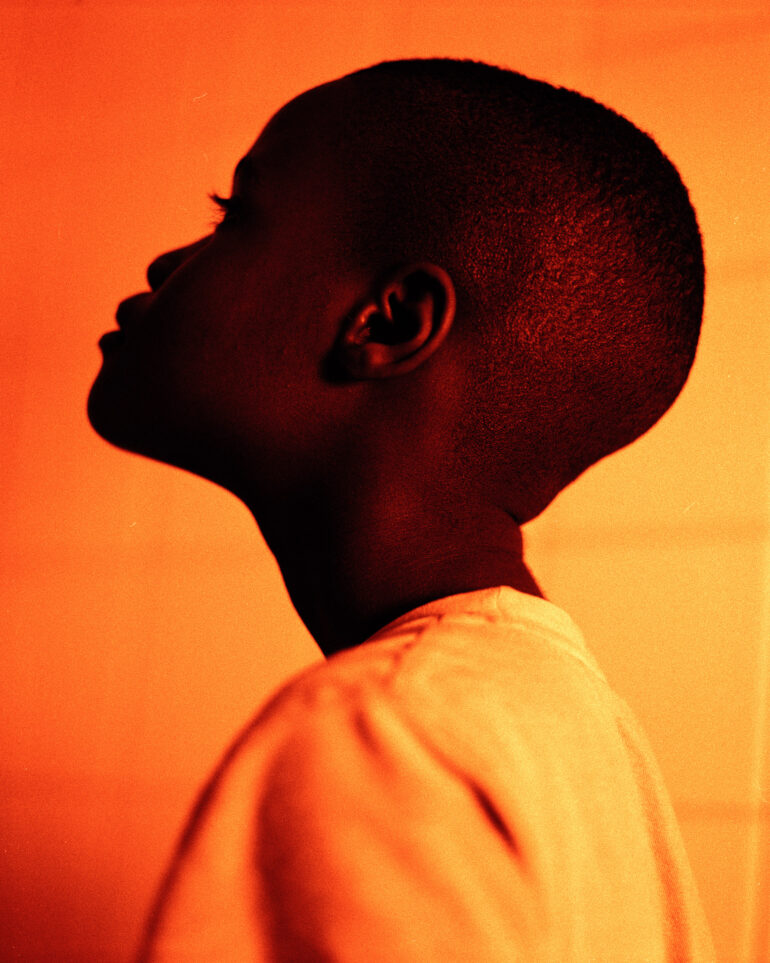

This constant observation and study grew into a photo project of her in recent years. “Since 2019, I’ve been photographing the men in my family in moments of rest and self-care in domestic settings, at home where guards are lowered. I wanted to document moments of intimacy, show alternative images of boyhood, and spend time with the people I love,” Melanie tells me about what she aims to capture in this ongoing project. It is a photo project showcasing the ideas of contemporary masculinity and the hopes and dreams of the men she knows.

The Challenges Ongoing

The ‘project ‘Of Boys And Men’ project began shortly before the pandemic. Like most creative projects, this one was halted when the world shut down for a few months. What made it even more challenging afterward was the migration of some of her family members to other cities. “I work full time and have other projects I’m working on, so finding time to continue has been difficult. I work on other projects to keep me engaged and inspired and build my skills. This project is self-directed and self-funded so that I can work at my own pace,” notes Melanie.

Some Of The Influences For This Series

Archiving life through photographs is something that Melanie Issaka finds essential. Documenting herself and those around her is important to her. When I asked her what influences the look and feel of ‘Of Boys And Men,’ she attributed much of that to her culture.

“My community, culture, and heritage play a massive role in forming my tastes and influencing the images I create,” says Melanie. “With bold and contrasting colors, my work often has a flair for the dramatics turning mundane scenes into performances. My creative process is about playing, experimenting, and seeing what is possible by bringing my ideas to life and making them tangible.”

But as tranquil as the images here might seem, Melanie describes the process as quite the opposite. “Most people describe me as calm, but my creative process is very frantic,” she clarifies. “I accumulate, expand, and take up space when working on a project, but there is a method to my madness (maybe). I’m often over the place and can’t rest until I’ve resolved a project.”

We, as photographers, can use our work to challenge stereotypes and biases by creating images that celebrate and uplift the experiences and perspectives of various black communities. In doing this, we can help expand on narratives of what constitutes black art and contribute to a more inclusive and diverse arts community

What Challenges Does She Still See Ahead?

“Systemic racism, underrepresentation, and lack of access to resources and opportunities such as funding and mentorship programs” are all hurdles for POC artists today, says Melanie. And she complains that she’s often been asked to modify her art to fit certain narratives.

“I have been approached by galleries who tried to encourage me to make certain types of work deemed “More African,” Melanie says. “Occasionally, it feels like people expect you to be a parody of yourself, dumb work down to make it more palatable for an audience. Shrink yourself to fit a box of someone else’s making. I am not interested in that,” she clearly states. “By advocating for greater diversity and inclusion in the arts, we must continue to amplify the work of Black artists and promote their visibility through various media, exhibitions, and publications.”