The question felt like words pulled out of a sci-fi novel, but there it was: Could a computer replace me? As a photographer, I’ve watched the list of lawsuits piling up between photographers/creators and generative artificial intelligence companies with the same siren call that a bird feeder seems to generate after seven days of quarantine. But as the courts ask the ethical questions on AI’s training data, I wondered, is generative AI good enough to replace a real photograph? This is how I found myself staring at a Stable Diffusion text prompt field, the bitter taste of coffee, and an undermined future in my mouth.

Table of Contents

AI Imagery Isn’t Photography

Since programs like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E 2, and Midjourney launched last year, the platforms have attracted both scrutiny and digital artists eager to try the new software-based tools. Artists have been quick to criticize the thought that a computer could be creative—in part over the idea of their work used without permission to train the software and the idea that their work could be replaced with a computer and a few text prompts.

What generative AI is doing isn’t being creative—but it’s taking the average based on a set of training data from actual creatives. The digital artists that have found “success” from the program typically use heavy Photoshop work to mix several generative AI images into something slightly realistic. With that said, they’re not photos, but composites.

Can AI Replace Photographers?

Curiosity piqued, I decided to attempt to recreate some of my favorite images in my portfolio with Stable Diffusion, a generative AI that’s free to use. Type in a few words into the text field, and the software will generate four images for each prompt.

I started with one of my photos that has sparked the most reactions on social media, an entire bridal party reflected in a puddle on a rainy day:

And this is what Stable Diffusion generated:

What generative AI is doing isn’t being creative—but it’s taking the average based on a set of training data from actual creatives. The digital artists that have found “success” from the program typically use heavy Photoshop work to mix several generative AI images into something slightly realistic.

I think there are faces in there somewhere.

Next, I tried recreating a bride and groom standing on a hill in front of a wedding chapel.

I can’t decide whether this is fuel for nightmares or hysterical laughter.

Okay, so weddings are out. Can AI re-create a portrait that I took of my toddler last fall, with the orange leaves bringing out his blue eyes?

Is that a toddler or a Brat doll with overly large eyes and seven broken fingers?

Fingers typing prompts with a bit more trepidation now, I asked the computer to recreate the photo that I took of my 10-year-old leaning against a vintage truck.

I wasn’t too worried about replacing portraits with generative AI because wedding and portrait photography is about capturing a specific person at a specific moment. As it turns out, Stable Diffusion still isn’t very good at creating anatomically correct people.

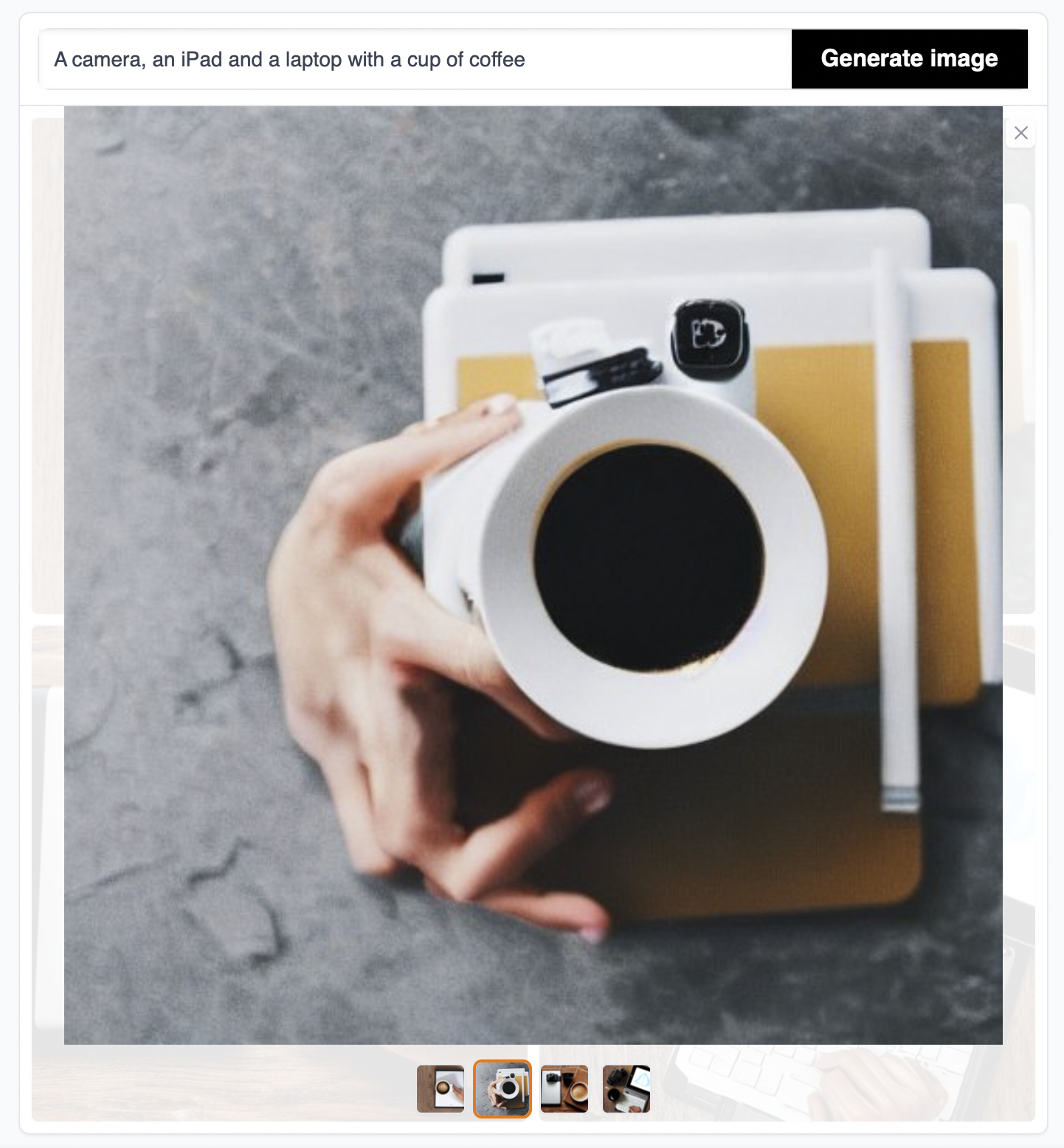

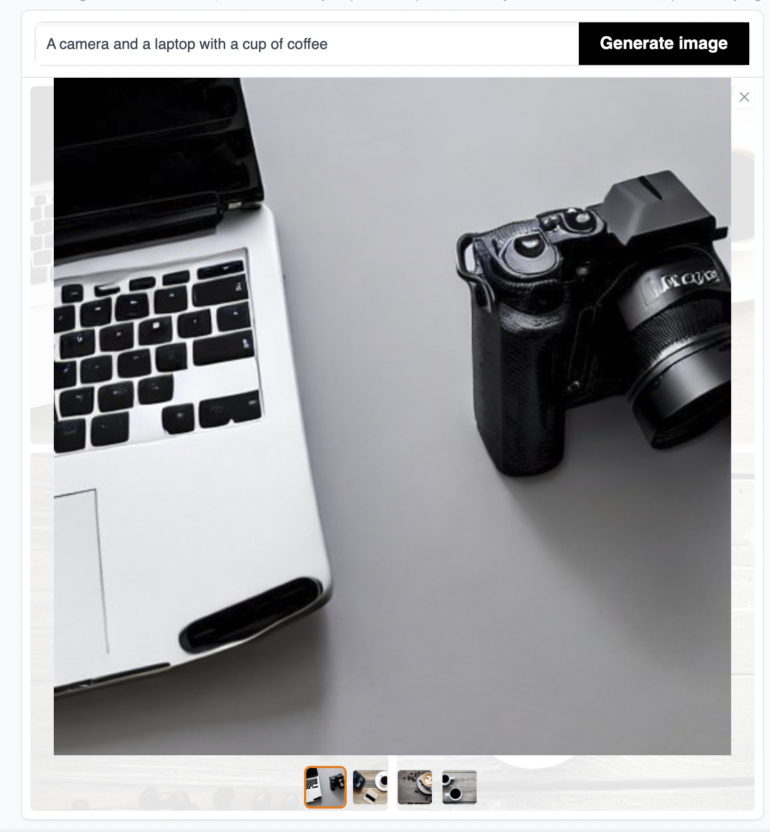

Before I had even started, I wasn’t too worried about replacing portraits with generative AI because wedding and portrait photography is about capturing a specific person at a specific moment. As it turns out, Stable Diffusion still isn’t very good at creating anatomically correct people. I had just photographed a few flat lays of coffee cups with cameras and keyboards for my website — could generative AI replace that hour I spent shooting a few props? After all, generic stock photos would seem to be more easily generated than a photograph of a specific person.

These are the cameras of my nightmares. Maybe if I keep it simple and just ask for a cup of coffee?

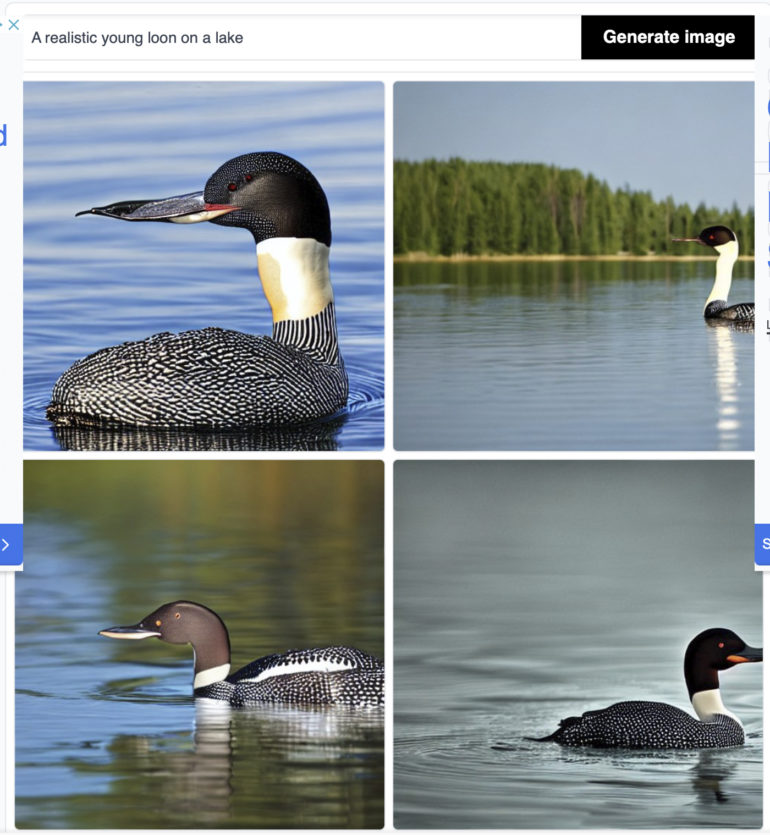

I then tried to recreate a few of the wildlife photos that I’d taken. The AI seemed to have a bit easier time creating a photograph of a loon than a human, though it generated an extra eyeball.

Proof that AI Doesn’t Understand Things

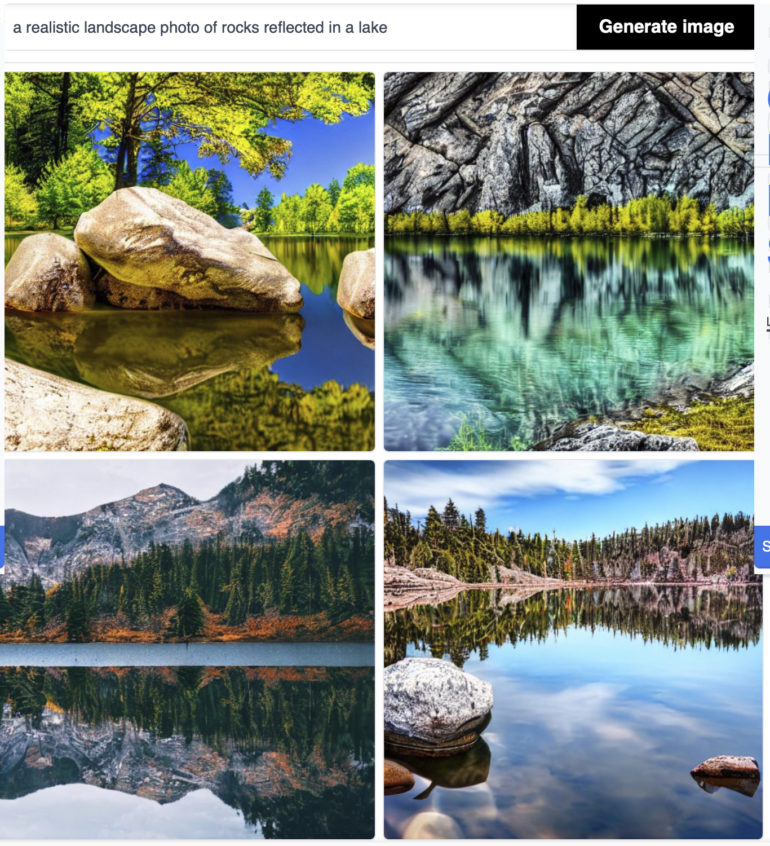

I then moved to photographs that require no understanding of a human’s or animal’s basic anatomy: landscapes. These look realistic if you’re quickly scrolling past one on Instagram, but they don’t hold up very well to close scrutiny.

Finally, after spending about an hour fluctuating between hysterical laughter and sick nausea, I could recreate a photo that looked sort of like a quick iPhone snapshot that I took on a road trip a few years back, which wasn’t even the photograph that I was attempting to recreate.

Excluding other art forms such as painting, the photographs that AI seems closest to replicating are photorealistic landscapes. Yet, these images don’t make me feel like I’m standing right there, as the real photographs do. Generative AI creates an average of the random assortment of web images that it was trained on — and, based on the results, the system was trained on entirely too many bad HDR attempts. Photographers in other genres should feel even more confident. A computer cannot replicate a memory exactly how it unfolded.

So Where are We?

The coming months are critical to how the legal system treats generative AI works — and how artists will be affected by such technology. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against all artificial technology in artwork—I use eye AF on my camera, for example. The photo of the couple in front of the church above was actually finished with Lightroom’s AI-based sky masking. But, it’s incorrect to call generative AI made from a quick text prompt creative, as the software is simply taking the average of a large number of real creative works and attempting to piece something new together. Generative AI images have more in common with a math book than a fine art album.

Generative A.I. has pushed art to the cusp of another era — the question to ask now is, what happens next? Will generative A.I. create another major change in the same way that Photoshop’s introduction did? Will it, like Photoshop, both be mistreated to fake images and create a new inspiring genre of digital artists?

Much of the answer will ride on ongoing debates in the courts as Getty sues the software trained on its images without a license and a software engineer tries to copyright a randomly created photo. The U.S. Copyright Office has already reverted an earlier decision, clarifying that a copyright issued to an AI-generated graphic novel was for the author’s original text, not the computer-generated images.

But, I think much of the answer also lies with artists. Will generative AI artists using a computer to create the vision in their mind and hours of Photoshop to finish the look properly label themselves as digital artists rather than photographers? Will generative AI be appropriately labeled as such? Will software engineers acknowledge that these AI programs would be impossible without human artwork? Will artists ever receive compensation for the work used to train such systems?

The results that artificial intelligence programs emit—at least from my tests—would take hours of Photoshop to create something passable. While spending hours working in Photoshop isn’t photography, it could conceivably be described as graphic design. Art can be AI-assisted, but it cannot be AI-generated. Art is intangible emotion in a physical form—without human input in some part of the process, it is just a random assortment of pixels.