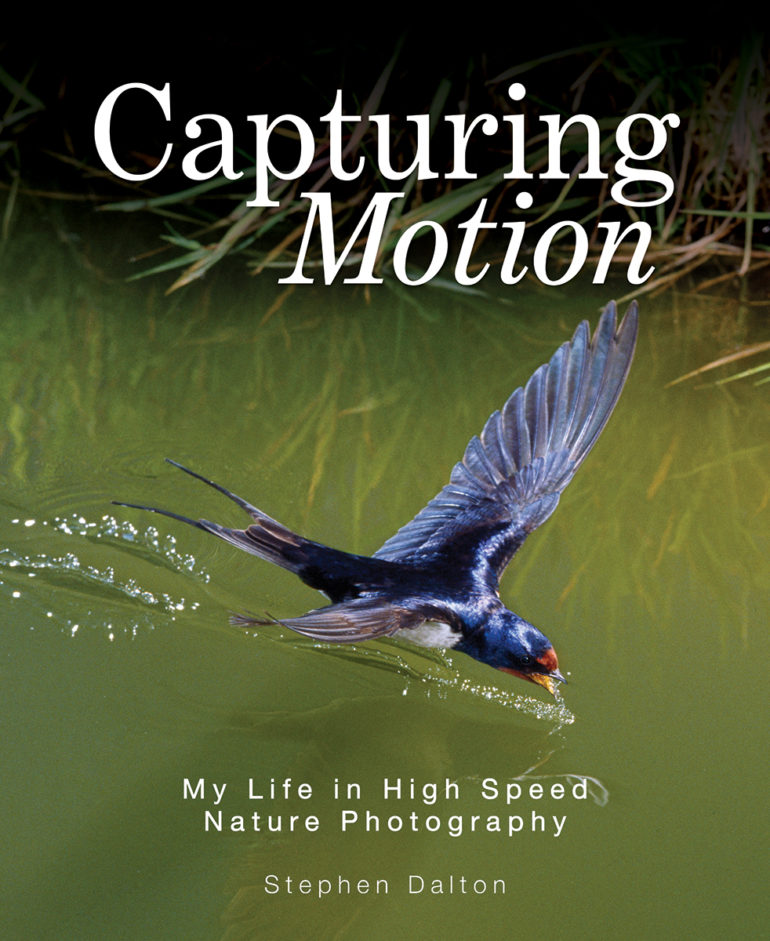

Stephen Dalton shot this mesmerizing image in 1973 in a single shot.

If you looked at the lead image today, you might think it was done in Photoshop. But you’d be wrong. Sadly, we’ve lost the art of creating in-camera. But photographer Stephen Dalton shared with us how shot this picture. In his book Capturing Motion: My Life in High-Speed Nature Photography, he shares short stories on this shot and so many more. Would you believe us if we said that this image was shot in 1973? And most importantly, it’s a single shot!

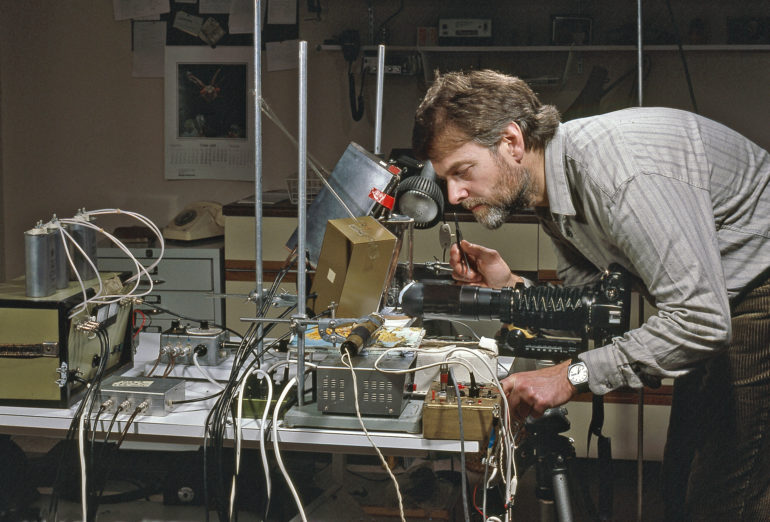

“I never took a setup image of the multiflash lacewing (or indeed for 90% of my high-speed pictures for that matter),” Stephen tells us via an email interview. “However I do have one for the setup of the leaping flea where I used three flash heads – you can see three flash heads in this picture if you can make them out through the electronic clutter. Oddly enough I never developed the facility to fire more than a single flash through one head for fear of damaging the flash tube and the length of time taken to charge the capacitors (about 10 seconds), so I had no option but to utilize separate flash heads for each flash.” He continued to state that it’s so much easier today with digital and better electronics in flashes. Personally, though, he’s not a flash of multiflash and black backgrounds. And we don’t blame him.

The Essential Gear of Stephen Dalton

- Leicaflex SL

- Leitz 100mm f/4 Bellows Macro Elmar f/11

- Kodachrome ll

How This Photo Was Shot in 1973

Lacewing flies are remarkable and underrated insects, possessing characteristics that belie their frail appearance. There are several European species, this green one being among the most common of over 20 species of brown or green lacewing flies and can be seen in gardens, parks and woodland where they help to keep aphids under control. With its large translucent lime-green net-like wings and golden eyes, it is a particularly beautiful insect but its most quirky characteristic was only discovered in the early 1970s during a photographic session.

In retrospect perhaps it is not surprising that an insect with such large floppy wings supporting a light body (low-wing loading) had an idiosyncratic mode of flight — one entirely different from bees or flies with their relatively small wings and rapid wing-beat frequencies. One of the first monochrome test images that I shot revealed that when taking off the lacewing fly did so vertically like a helicopter, with its wings bizarrely contorted (see page 22). Further photography revealed that sometimes they flew a complete loop only to land in more or less the same spot. To see how this extraordinary aerobatic maneuver was accomplished I set up three flash heads and set the flashes to fire in sequence with a predetermined delay. The photograph shown here is a typical result where the insect performed a half-loop, effectively taking off backward. This explained why it often landed facing in the opposite direction on the same spot. Whether this is a clever aerial maneuver to escape predators or is due to aerial incompetence is open to question, but knowing the direction evolution takes, I suspect the former.

A custom-made box of tricks with timer delays to fire each of the three flash heads had to be constructed to acquire this picture. Nowadays, such images can be achieved far more simply by incorporating a “simple” off-the-shelf timing chip in the circuitry.

Like other members of the order (Neuroptera), such as ant-lions, dobsonflies, and ascalaphids, lacewing flies, both in the adult and larval stages, lead highly predatory lifestyles, feeding on small insects such as aphids. The larvae are particularly crafty.

They disguise themselves by sticking the dried-up carcasses of their victims on their spiky backs, which allows them to creep about and take their prey by surprise. The larvae of some of their neuropteran cousins such as antlions behave in an even more nightmarish way. They lie concealed in the bottom of a conical loose sandy pit, which collapses when potential prey approaches the crater’s rim. Woe betide any small insect that falls over the rim of the “event horizon” and struggles to get a foothold.

The above was an excerpt from Capturing Motion: My Life in High-Speed Nature Photography. It and the photos here are used with permission from Firefly Books LTD and Stephen Dalton.