All images by Jonathan Hodder. Used with permission.

Photographer Jonathan Hodder is a British-Filipino national currently working for the United Nations in Southeast Asia. He tells us that he is “designing and managing projects on democracy and human rights.” His job takes him around to many places in the world, and so he manages to photograph many people in various walks of life.

“Previously, I only used the streets to hurriedly get from A to B, but a camera has this remarkable ability to make time slow down and appreciate the way people interact with each other, consciously or unconsciously.” he tells the Phoblographer. “These moments can often be aesthetically beautiful, emotionally very strong, or a combination of both. This is why I fell in love with street photography.”

He’s been into seriously shooting since 2014 and

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

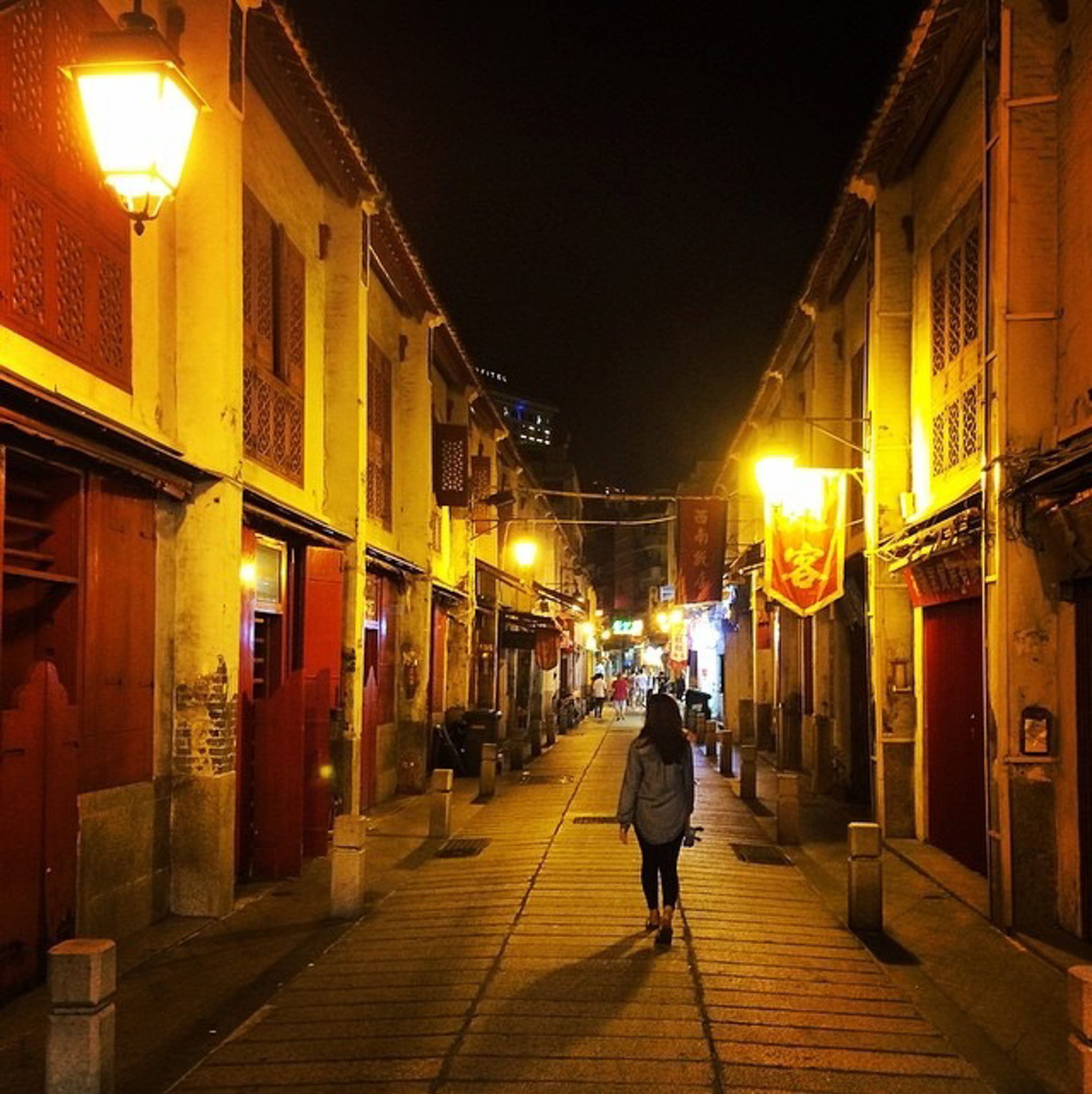

Jon: While growing up in the 90s, my parents had a number of film cameras which I would borrow from time to time, taking snaps of friends and family. I did not get into photography properly until 2014 while in Macau for the first time with my girlfriend. We arrived in the late afternoon and checked into a small hotel found in the old colonial part of the city. I woke up in the evening after a brief nap and decided to go out exploring a little, and I was immediately taken back by how alive the streets still were. The narrow cobbled roads had been lit up by low hanging lamps, and on either side were small stores, each one selling its own unique handmade food or product.

I returned to the hotel room, woke up my girlfriend, and dragged her outside and through the streets, taking photos along the way which came out much better than expected. The photo entitled “explore” is of my girlfriend sleepily walking back to the hotel on this very night. It’s the photo that really ignited my passion for photography.

Phoblographer: What made you want to get into street and documentary work?

Jon: Previously, I only used the streets to hurriedly get from A to B. While walking, I would notice certain moments which I found interesting or important, usually human expressions or actions, though they were few and far between. However, since getting into photography, I found that a camera has a remarkable ability to slow down time and focus your attention. I realised very quickly that these fleeting moments were actually happen all the time – photography simply opens your eyes to them, and is kind enough to provide you with a keepsake.

Phoblographer: These days, you work for the United Nations; does photography play a part of that?

Jon: I work for a UN agency based in the Philippines, helping the governance team design and manage projects on democracy and human rights. Our primary focus is on improving the condition of those who live in poverty and conflict, and the job itself has taken me to the more colourful places in the Philippines and wider Asia-Pacific region.

Photography is something I do in my spare time and, while I’m still getting to grips with it, I am ashamed to say that the relationship between my job and my photography is presently very one-sided. While the UN has positively influenced my photography, I have given very little back in the form of photos to be used for publication and advocacy. Some colleagues that are aware of my photos have been critical of this, and I will be changing things around before the end of the year.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about your approach to photographing people in public. Does anyone ever give you a hard time? How do you respond?

Jon: Everyone has different techniques to capturing candid photos of people in public. Some photographers that I know talk to their subject before or during the shoot, and they get excellent results. Others steal quick shots of people while they walk quickly past them. I’m good at neither, and to get shots that I’m happy with, I find that I need a decent amount of time to compose my shots; to be at very close proximity; and to top it off, for them not to notice me while I take their photo.

In busy locations this is actually quite easy, and you can raise your camera up to your eye and compose without alerting the subject. In situations where this is not possible, I will try to make the subject feel comfortable with my presence so that I do not interrupt whatever it was that attracted me to them in the first place.

To do this, you can try hanging around the area for a few minutes, buying something from a street vendor, or if you’re with someone, engage in a brief conversation. Eventually the subject gets used to you, loses interest, and goes back to their routine. At this very point, I find that your subject’s guard drops momentarily, and you now have a few seconds to compose 3-4 good shots – sometimes right in their face – before they start to notice you again.

The approach is not perfect, however, and there will be times when you get caught out. Most people usually react with surprise, shyness, or will even enjoy the attention and strike a pose. But I have had two bad encounters. The first was with a woman who was washing her laundry by a creek. I was being too obvious with my camera and, well, she was washing her laundry, and she angrily and rather understandably waved me away. The second occasion was in a dockyard while I was trying to take a picture of off-duty marines playing basketball with the sun setting behind them. However, two heavily armed soldiers stood in front of me, blocked my view, and firmly denied me that opportunity. In these situations you just have to look the person in the eye, apologetically raise up your hand (or in the case of armed soldiers, two hands) and walk away.

Phoblographer: What do you really try to get across in your images? A lot of it seems like documenting every day life in the streets.

Jon: This is a very difficult question for me to answer, mainly because I’ve never tried to articulate this into words before. My job requires me to be very methodical and rational, while photography is a release from this. When I am out shooting I try to do very little thinking and instead allow myself to be drawn to whatever I find interesting, which tends to be two things which, I am sure, is common to many other photographers.

The first is an action or scene that provides an interesting glimpse into someone’s life, such as commuters catching a quick dinner with strangers at a roadside vendor, or a store owner getting jealous with his wife who was chatting too long with a male customer.

The second is an action or expression that conveys a particular emotion, at least to myself. Sometimes this can be very obvious, but my favourites are when it is more subtle. One example is the photo taken in a very loud and busy market, with a little girl sleeping in her grandmother’s lap. In spite of the intense heat, noise, and her incredibly award sleeping position, the girl was at complete peace, because she was in the safest place on earth.

Phoblographer: What do you feel are some of the toughest things about photographing people in the streets?

Jon: The biggest difficulty is probably location. If I was still living in the UK suburbs (or even some of the cities) there is a very high chance that I would never have taken up photography in the first place. Of course, there are British photographers which can and have taken great photos of architecture and landscapes, often using light and geometry to breathtaking effect. However, my interest has always been in the human condition, and I have found it very difficult to capture that in the UK, most probably because people generally prefer to express themselves privately indoors and not publically on the street.

This is why I feel so lucky as a photographer to be based in the Asia-Pacific. Here, the climate is often warmer, society is less regulated and more spontaneous, and as a result of all this, people really live their lives on the street. Street life over here is so dynamic, so vibrant, so captivating, that wherever you point your camera there’s a good chance you’ll be shooting something interesting.

Phoblographer: What gear are you using these days? How does it help you to get the shots that you want?

Jon: Currently I’m using the Leica X (113). It suits me well because it is incredibly simple to operate manually – to the extent that you can adjust the manual settings even before you switch it on. It’s relatively small, so it doesn’t attract a lot of attention, and it has a warm, sharp rendering quality of which I am very fond. The autofocus isn’t the quickest but I picked a new model up in Hong Kong at a huge discount so I couldn’t say no.

In the near future I am looking to buy a second hand film camera with my eye on a Canon III/IV or a Leica M2. There are days when I want to take more time and patience with my photography, hang around in a spot of great lighting and waiting for a moment to happen, and I feel that a rangefinder would be perfect for this. I know there are digital rangefinders nowadays but they’re very expensive, and I really want to get back into film, partly because I want that nostalgic experience of opening the envelope at the developers and viewing the photos for the first time, and partly because these mechanical cameras are built like tanks. The thought of having a film camera that would last me for the rest of my life, and passing it on to someone afterwards, is one which I hold with great regard.

Phoblographer: Tell us the story behind your favorite image.

Jon: The black and white photo of the young woman selling “malongs” (Filipino word for a cloth you can wrap around your body or use as a blanket to sleep in) is very important to me. It was taken in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao in the Philippines, an area which has long been the poorest, most desperate part of the country torn by conflict. The rebels, who have been fighting for greater autonomy, and the national government have been engaged in peace talks which had been making very good progress until last year, when security personnel ventured into a rebel camp looking for a wanted man. Shooting broke out, lives were lost on both sides, as well as civilian bystanders, and the peace process took a major setback. I travelled to the region shortly after this incident, and the young woman’s face in the photo is a clear expression of the despair felt amongst so many people. There is now a need to protect and strengthen the youth’s desire for peace, so that they themselves continue to demand for and be a driving force behind the peace process in the coming years.