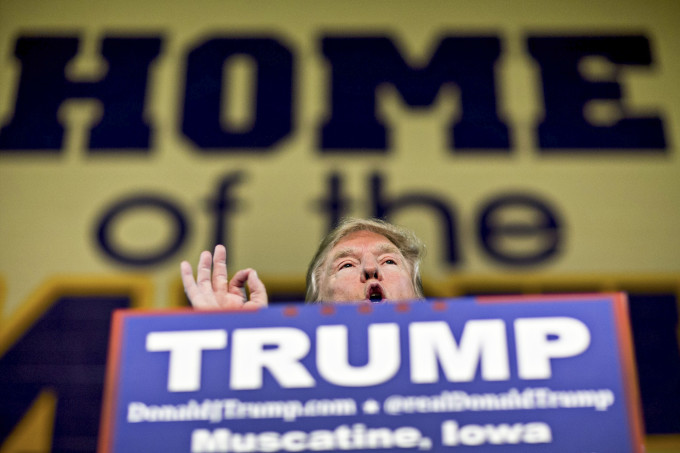

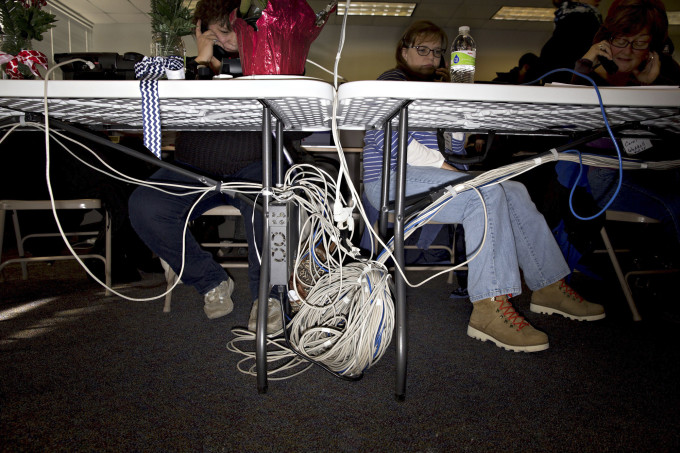

All images by Daniel Acker/Bloomberg. Used with permission.

Daniel Acker is a freelance photographer based in rural Illinois outside of Chicago. He’s been shooting for many years now, and the evolution in the way that news is transmitted in that time has been a remarkable one. As a contract photojournalist for Bloomberg, he also works for the New York Times and the Wall St Journal. So far, he’s been on the current presidential campaigns in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Florida.

“After a few conversations with some photographer friends I decided I would post some professional imagery alongside my personal stuff on IG.” says Daniel. “Within a few weeks of posting images from political events I was featured by Instagram, and I went from 600 followers to nearly 25,000. It was wild.

We talked to Dan about what it’s like covering the election season.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

Daniel: Like many people, my interest was sparked by my Dad rockin’ around with his Canon AE-1 Program. He had the Cokin filter set where you could shoot through keyhole and heart shapes. It was awesome. I never got much into the filters, but I did start photographing my friends and I playing basketball in my front yard, doing our best Michael Jordan imitations. During one of those sessions I dropped the camera, and shattered the front element of my dad’s 50mm lens. I thought I was dead meat. When he got home he unscrewed the broken UV filter and handed the camera back to me. My mind was blown, and I was a dedicated user of the UV filter from that day forward. Never leave home without it.

From there I took a high school class, went on to take as many classes as I could during three years at a community college, and then finished up by earning a BFA in Visual Journalism from the Rochester Institute of Photography (RIT) in 2000.

Phoblographer: What made you want to get into documentary/photojournalism work?

Daniel: When I graduated from RIT I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I had worked for a commercial photographer for a few years during community college, and I knew that wasn’t what I wanted. We did quite a bit of still life and heavy industrial work. It was interesting, but schlepping lights into a factory to photograph the latest giant boxy metal machine that XY company had designed wasn’t for me.

I was fortunate to land a job at Bloomberg News in NYC straight out of college, and I started there in June of 2000. The photo department was in its infancy and I was the first external hire. I signed-up to be an editor, thinking that’s what I wanted to pursue. Over the first year or so I began to photograph guests during in-house editorial board meetings, shooting random product illustrations for news stories etc.. I realized I enjoyed that much more than editing and slowly made the transition that direction. It was a wonderful place to work, and I was offered many opportunities by my boss, Claudia DiMartino, that I wouldn’t have otherwise had on a larger staff. She threw me into situations I probably didn’t deserve to be in, and I learned alongside some of the best in the business along the way.

There is one example of this I can point to which truly changed my professional career path. I was assigned to go on a trip with Vice President Cheney to the Middle East in March of 2002. I didn’t have a passport, and the trip was less than a week away when it fell in my lap. The White House Travel Office hooked me up and I went to DC and got a passport in just a few hours. My mind was blown.

When I arrived for the trip I found out I was one of only two photographers going, the second being J. Scott Applewhite, senior AP photographer in Washington. Scotty had been photographing professionally for basically the entire time I had been alive, and could have brushed me aside and visually annihilated me the entire trip, but he didn’t. He had been on many trips like this before, and he helped me every chance he could get. The trip was full of “ok, when we run into this room this is what you’re going to see…we’ll be there for 30 seconds, and if I were you, I’d consider changing out that wide zoom for a slightly longer lens.” Now, he did annihilate me visually, don’t get me wrong, but the things I learned from him during that 10-days went on to inform me for years. This was also my first foray into national politics, and I think my interest in the campaign trail spawned in some way from that trip.

Phoblographer: You’re a photojournalist that’s been following the US Presidential campaign trail partially by using Instagram. Years ago, we didn’t really have that opportunity but now we do. How do you think the platform has changed the way that we can control the message and get news out there faster?

Daniel: I began working in Iowa on the campaigns early in 2015, and I didn’t post any of my “professional” work until Jan 24, 2016. I was using IG as a platform for all of the images I would take along the way, but previously would gather dust on my hard drive. I’m not that good at keeping up my website, I don’t have a blog. I just never found a solution that was simple enough for me to actually take the time to follow through on a regular basis. When I found IG, of course, all of that changed,

After a few conversations with some photographer friends I decided I would post some professional imagery alongside my personal stuff on IG. It was partially so that friends/family would better understand what it was that I did. The general public doesn’t have a clear understanding of what photojournalists do, and most people who knew I was a photographer assumed I did weddings and senior portraits for a living. So I thought I’d give it a shot and see what happened. I figured I could always pull back from it if there was a followers revolt.

Within a few weeks of posting images from political events I was featured by Instagram, and I went from 600 followers to nearly 25,000. It was wild. Now, I have questions about what percentage of those followers are actual people vs. spam accounts, but even if 50% of those are fake it’s still an amazing jump in eyeballs seeing my work.

I don’t like to think of a photojournalists work as “controlling the message.” I try to make the most interesting image possible regardless of the subject in front of me. With assignment work I typically have very little say over who I’m photographing on any given day. This isn’t to say I don’t have opinions or preferences, or that I don’t consider the larger news context surrounding an individual/event when I’m on an assignment. If I let my personal preferences creep into my work in a way that makes my imagery biased, I feel like I’m letting the public down. I try very hard to stay above the fray in that regard.

In the larger context, however, IG and other social media platforms have pushed the ability for self-branding to an entirely new level. Candidates can push out their message directly to the public in an unfiltered manner at any time of the day or night. The traditional news cycle is out the window. 24-hour cable news started that change, but social media has expedited the process dramatically. Everything happens in real time, and ultimately the public should benefit from that, but I’m not sure that’s always the outcome. People get drowned in content through these platforms, and at times I think its difficult to parse.

From a photographic perspective it is the same. We can push images directly to the public. There is no delay, it’s all real-time and coming directly from the creator in many cases.

Looking through my feed as an example, you’ll see images of candidates from both sides of the aisle. If a follower of mine see’s an image, and that makes them pursue more information about an individual, or raises their awareness of the presidential race in general, I think that’s a good thing. Before they had to actively look up my website, which, as I mentioned earlier, is never as up-to-date as it could be. My IG feed has images I made 5 seconds ago, and that dynamic shouldn’t be discounted.

I think professional images also stand in stark contrast to other images on Instagram taken by the general public. Despite everyone having a camera in their pocket these days, the need for professional, high-quality imagery, hasn’t diminished.

Many have coined this election as the “selfie election,” and it’s true. Folks literally climb over each other in their quest for a selfie with a candidate. I’ve watched the dynamic unfold countless times where a person has their back to the candidate the entire time, holding their phone in the air trying to get the perfect angle. If they only turned around they could have met this individual, shook their hand, looked them in the eye, perhaps exchanged a few words about an issue important to them. Platforms like IG make the selfie quest legitimate, and the smart campaigns quickly realized how important this aspect of campaign marketing has become.

From a journalistic perspective, it’s a bummer. No one is interacting, they’re just taking pictures of themselves to post on social media, and the “moments” of emotion that come with human interaction, and can make for the most interesting photographs, are largely gone. This is unfortunate, and although they still exist, it’s more and more difficult to find and capture them.

Phoblographer: Of course, Instagram is an excellent platform for journalists to be able to get the news out there. But besides getting the information out there, how do you think photojournalists can use the platform to ensure that they can keep paying their bills?

Daniel: This is the ultimate question. The sheer quantity of imagery available to publications is overwhelming. I think the roll of photojournalists in the larger public conversation has not changed. Providing high-quality unbiased imagery is my motivation, and these platforms have simply increased my ability to get photographs in front of as many people as possible. I have had a couple of publications contact me about using political images they saw on IG, and these are connections I likely wouldn’t have made otherwise. In the same way the candidates can use these tools as a marketing platform, I believe this to be the largest benefit to the professional photographer as well. It’s simply another channel to bring your work to editors and publications you wouldn’t have otherwise reached.

Phoblographer: You’re a photographer that uses his DSLR to shoot and then shares on Instagram. What gear do you typically use?

Daniel: I’m currently using Canon equipment, a 5D MK III and a 1DX. I try to keep my gear to a minimum, and typically carry a 24-70 f/2.8, a 70-200 f/2.8, a 85 f/1.2 and a 300 f/2.8. I have other lenses, but those are the one’s I use the majority of the time. Prime lenses are great, and if I were to change anything I would likely add a 24, 50 and 135 to my kit and ditch the zooms.

Phoblographer: For you, what determines the images that you share?

Daniel: I try to post the images that are the most interesting to me, without being repetitive and exhausting. I tire quickly of the feeds which contain 15 similar images from a single event, and I try to keep that in mind when I’m posting. It’s so easy to push images out that the temptation to over-post is one that I have to actively fight. I may file 25-30 images to my editors, and post 2-3 to my IG account. Each photographer has a unique way of seeing the same scene, and I try to highlight the images that are representative of my personal style. I like lens flare, I like images that are nuanced and not always the obvious candidate at a podium type shots. These are necessary evils from an assignment perspective and certainly have their place, but aren’t usually the one’s I choose to highlight on my IG feed.

Phoblographer: A number of people have told me about how intense it can get for journalists at a political rally. What’s the experience been like for you?

Daniel: The actual act of making pictures is such a small portion of what we do on the campaign trail. The logistics of security and access occupy most of my time before and during an event. These can be difficult to navigate, particularly when you feel like there is a picture to be made in an area you’re simply denied access to.

There is definitely a theme from some of the candidates that the media is the enemy. That we’re a biased group of people who should not be trusted. This isn’t without merit in some cases, but on the whole I don’t believe that to be the case with the majority of the photojournalists I work alongside.

Keeping your cool, being respectful of people who don’t automatically extend that same respect to you, and making the best imagery possible with restricted access is where I try to put my attention. I have never felt personally singled-out, but the larger assault on the media is something that’s difficult to escape most of the time.

That said, my experience has been largely positive throughout the 14 months I’ve been working on the campaign trail. If you don’t treat people fairly, you can’t expect anything else in return. My goal is never to put myself in a position where it’s my personal actions which limit my ability to cover an event. I’ll lobby to get better access any chance I get, but at some point I have to accept the situation for what it is and make the best photographs I can. You can get lost in the world of “if I could only get over there…” to the point where you no longer see what is right in front of you.

Phoblographer: I feel like everyone who wants to get into photojournalism has a romanticized outlook on it and that they don’t necessarily think about all the danger and hardships that photojournalists sometimes go through. How has your outlook on the industry changed over the years?

Daniel: Life on the road is difficult. Time away from family, travel and event logistics, equipment management, and horrible food are hallmarks of the campaign trail for me. It’s extremely demanding physically, emotionally, and professionally. I tend to crash hard when I return home from a stint on the road. You don’t realize how much adrenaline your running on after working 18 hours a day for weeks on end. It’s both the thrill and the sacrifice of this sort of work. It’s addicting in many ways.

I have many photojournalist friends who have spent months and years of their lives covering conflict and social unrest. I’ve had friends and acquaintances lose their lives documenting these situations around the world. This should not be taken lightly by anyone thinking of pursuing this as a career. If you walk around the world with a camera, people question your motivations. It’s that simple. The benefit of the doubt that you’re not up to something nefarious is simply not extended in the way I believe it once was. Skepticism rules, and you need to be able to do your work despite that. This can be a challenge at times.

The biggest change I’ve seen over my career is the blanket use of one word to justify any action by an individual or an organization to limit access to a situation: security. It has become the default answer to any inquiry which questions the logic of a pre-conceived narrative someone is seeking to establish. This could be something as simple as a particular spot in a room you’d like to photograph from during a political rally, or the complete denial of access to a facility or breaking news scene.

I’m not suggesting their aren’t legitimate security concerns, but the word is used so flippantly it’s becoming meaningless. I think this dynamic will only increase moving forward, and for a profession which relies on access, it’s disheartening.