Have you ever been asked by friends and family to, “Come to our party, and bring your camera!” when you’re invited to an event? Sure, you may be the photographer amongst friends and family, but sometimes you’re tasked with things that you don’t want to shoot. Knowing what I was getting into beforehand, I chose to document the final breaths my grandfather breathed and his final goodbye to my family. But along the way, I learned a heck of a lot as a photographer: about shooting, self-composure, and getting the most out of your gear.

First off, consider this: I’ve been a wedding photographer and photojournalist for a couple of years and I am currently a highly active street photographer. Getting the shot is no problem for me at this point in my progression. I’ve shot in big churches, city hall, backyards, wedding halls, mosques, you name it I’ve probably done it. But a funeral is different. During the ceremonies, everyone is silent. Everyone. And that means that the sound of the quietest camera will be heard and echo through the hall like the sound of a baby crying at your favorite Broadway musical.

This was the first time I’ve even attempted funeral photography.

I decided to take my 5D Mk II, 35mm f1.4 L and 85mm f1.8 with me: and nothing else. Why no flashes? I wanted to stay incognito and fast primes will do the job well. Why not the 24-105mm f4 L IS? F4 is too slow in this case; and even f2.8 was too slow in most situations as well. The 5D Mk II was chosen because it i the quietest of my DSLR cameras while giving me the absolute best image quality I can get.

Or so I thought.

The 5D Mk II should probably never be used to photograph events that are extremely quiet. In fact, I wouldn’t even recommend a DSLR. The entire time that I was shooting, I kept thinking to myself, “Man, the Fuji X100 would come in handy right about now.” The leaf shutter on that camera is super quiet and the camera is also very unobtrusive. It would indeed have been a much better choice in a situation like this.

And no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get around the loud sound of the shutter (which I’ve always thought to be super quiet). Even when shooting with my 85mm lens to give me some extra distance, it was still loud and people would hear me despite being further away than with the 35mm. What was worse was that it was always family that looked at me or said that the shutter was too loud. However, they were thankful that my camera didn’t have a flash.

Later on in the project, it came down to having to move as slow as an army sniper combined with reading the body language of the subject. For clarification, snipers move agonizingly slow to avoid detection. As a photographer, you need to perfectly coordinate your movement speed, reading body language, and capturing a photogenic moment. That’s much tougher than it sounds. Imagine losing that perfect moment because you couldn’t move fast enough or get your settings right quick enough.

While the Fuji X100 would have been a very quiet choice, silence isn’t everything. In fact, my 5D Mk II’s images blows nearly anything I’ve shot with away. The reason for this is because of my special custom settings on the camera combined with my editing style. With this said, the camera and I celebrate a long relationship of use: which has also helped me to figure out how to meter with the camera to get the best shots I can.

Metering and the post-production process is extremely important. One of the reasons why many of the top professionals say that you need to try to, “Get it right in camera” is because of the fact that they shoot lots of images. When you shoot that many (and I shot at least 700) you’ll need to narrow the images down to the ones you want to use and then carefully edit each of them. If the settings are right the first time around, you’ll have less work to do later on in the editing process.

Like a wedding though, I learned that funerals have their own processes. Sure, I knew this beforehand, but then come the logistics of trying to actually photograph one and doing a good job of it. There are tons of little details that you may miss. Additionally, this project hit close to home.

So how did I force myself to do it? I’d like to thank my mentor for that: who photographed families and people for years as they died slowly of Alzheimer’s Disease. I learned a lot from him. More than that though, it takes intense concentration and a tremendous amount of faith in yourself.

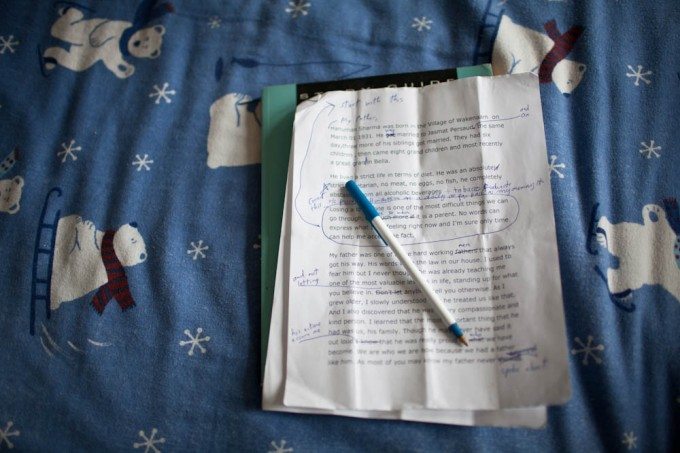

Like any good photojournalistic story too, you should include the small details and never overlook them. Beyond gear though, it’s about capturing moments: the emotional, the intimate, and unusual. Those will make for the most interesting photos. But while shooting, you’ll need to try to find unifying factors to tie the photo into the entire story.

This particular story was the hardest story to ever tell because it hit so close to home with the death of my grandfather. Even worse is when people ask you to take photos of certain things. This happens all the time at weddings, but after a while you tell the subjects that you need to get back to photographing for the Bride and Groom. But at a funeral, and one that involves family, they track you and it’s much harder to explain to them about the subject matter. Indeed, many people want to forget. But also, some want to remember.

And in the end, you also need to realize that the most important thing is family. Whether you’re photographing the project for yourself or for a client, the story of family is always the uniting factor at a funeral, wedding, or other similar events.