Relegated to hard disks, USB drives, and the lately often unseen CD ROMs, digital photos aren’t as lovingly stored as their predecessors. This wasn’t the case with negatives and photo prints, which had a tactile experience when viewed. Honestly, there’s no other experience like holding a photo print or a 35mm negative strip in your hands. If you’re like me, your collection of these precious negatives won’t lie in drawers or collect dust somewhere. They would be carefully stowed away, well protected inside photo wallets. And if they could talk, those envelopes of desire could each tell some lovely stories of their own.

Images of photo wallets used in this article obtained from Dr. Pollen’s book have been labeled as such. The other pictures are from the author’s personal collection.

Dr. Annebella Pollen is a professor of Visual and Material Culture at the University of Brighton. We’ve featured her before when we discussed her book Nudism in a Cold Climate. Her latest book, More Than a Snapshot, showcases a century’s collection of photo wallets from the UK. “These humble items might seem to be of lesser importance than the photographs they hold,” writes Dr. Pollen. She rightfully adds that the messages they showcased and the visual styles they promoted are missing in today’s fast-paced digital world. Over a century of various changes in photography, print wallets evolved in style and scale. This reflects both the growth of camera ownership and the gradual decline of commercial film processing.

All the wallets in this book are from my own collection of many hundreds of examples, built up over more than a decade of rummaging at bric-a-brac stalls and car boot sales. I rarely spend more than a pound or two and many wallets I have received free from dealers employed in end- of-life house clearances. They are battered and bruised examples rather than pristine specimens.

Dr. Annebella Pollen

Table of Contents

It Started With Kodak

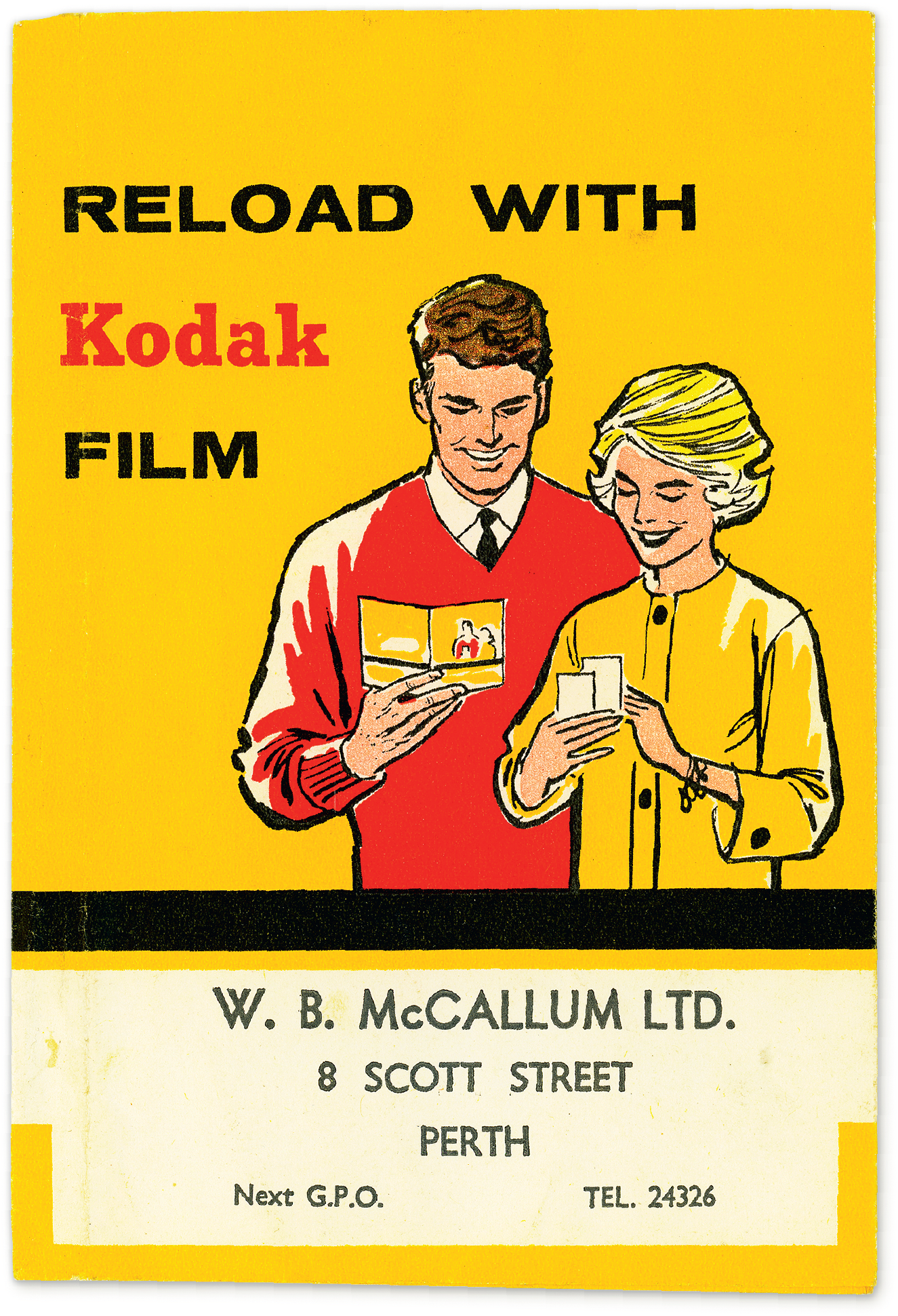

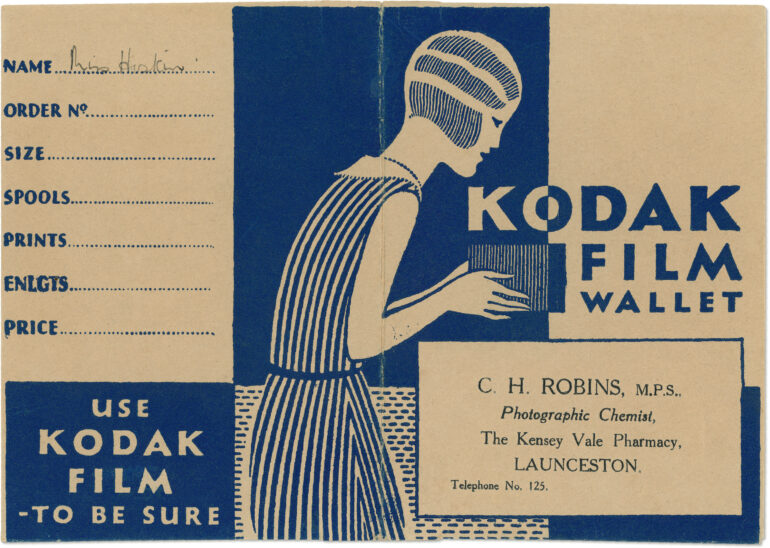

The book starts off with a look at the history of photo wallets. Launched as ‘print wallets’ by Kodak in 1908, these simple envelopes were designed with dual compartments to hold prints on one side and negatives on the other. These wallets feature designs sourced from competitions and commissioned illustrations. They aligned with Kodak’s advertising campaigns and promoted snapshot photography as an accessible and enjoyable activity. The primary target audience for these campaigns appeared to be women and children.

Photo wallets significantly shaped photographic ideals, promoted products, and communicated social norms to photographers and their near and dear ones. They also showcased Kodak’s other products and services, fostering a connection between processing and the broader Kodak universe. Kodak strategically positioned snapshot photography as a feminine pastime, featuring female subjects in white attire to symbolize photography as a clean past-time. The iconic Kodak Girl character was depicted by renowned British illustrators in various settings and fashion trends. These designs also helped spread the carefree image associated with snapshot photography.

Her hemlines and hairstyles changed over time, but whether her camera was a Box Brownie in the 1920s

or an Instamatic in the 1960s, the smiling Kodak Girl was an aspirational model in line drawings and photographs for over fifty years.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

I Enjoy The Flashbacks They Provide

If there’s one photography brand that always takes me back to my childhood experiences with 35mm, it’s Kodak. Their “Express” branding was all over town in the numerous studios and developing centers owned by the Rose Studio and Stores company in Dubai. Countless trips to their branches for passport photos and developing negatives gave me a strong association with the red and yellow colors of the brand. The once-annual trips there to have a family photo taken amidst colorful backdrops were a treat. And there’s nothing like opening up a photo wallet from the past and finding forgotten pictures of a time gone by.

Remember Boots the Chemist?

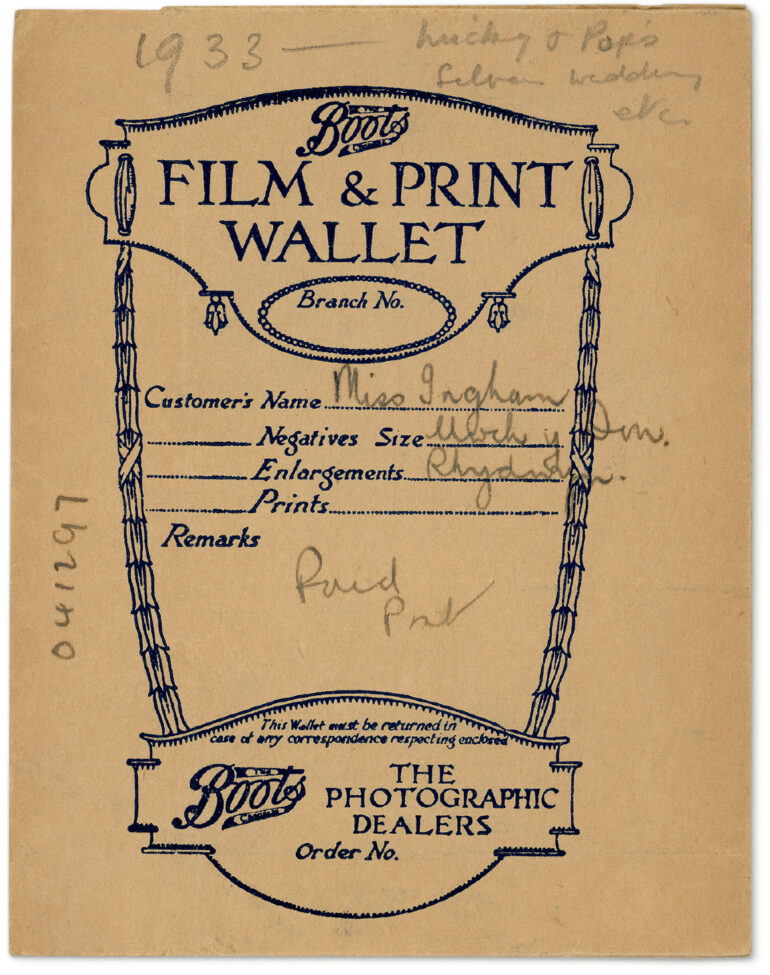

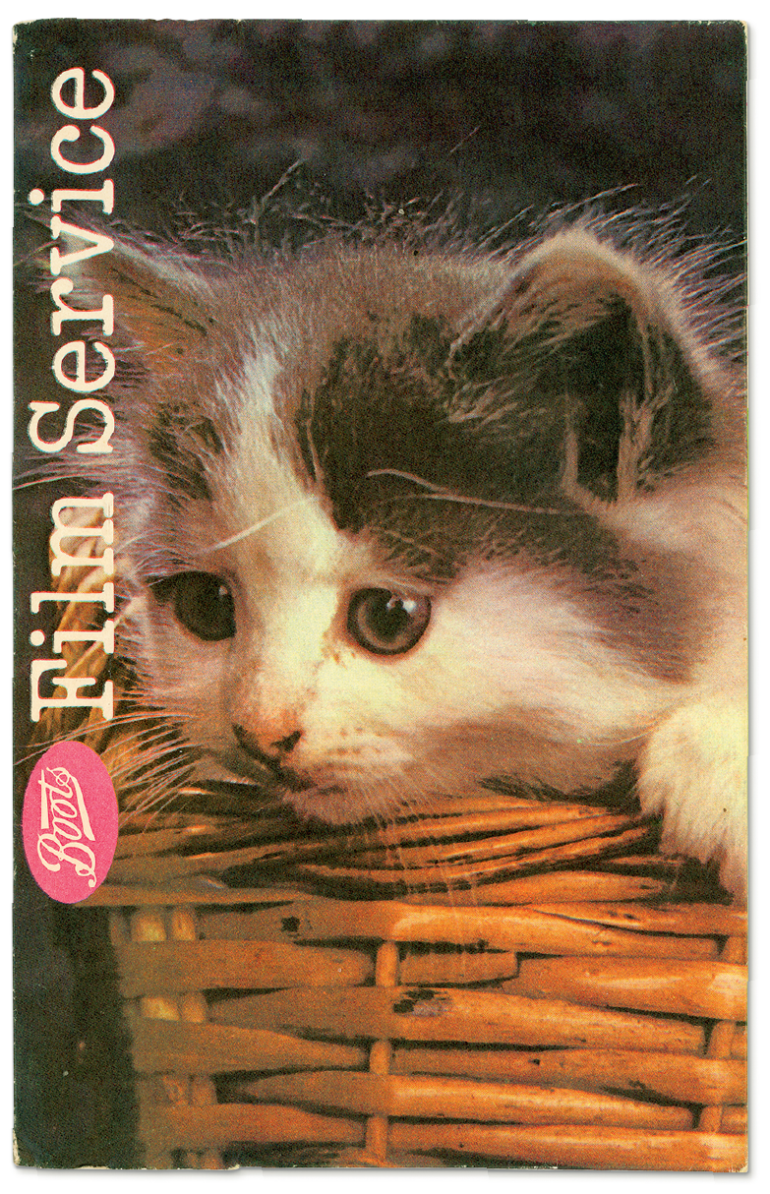

Known for its expansion in the pharmaceutical market, Boots The Chemist began promoting processing prominently during the First World War. They positioned themselves as a reliable and efficient provider of developing and printing services. Unsurprisingly their photo wallets resembled dispensing envelopes and created a symbolic connection between the medical and photographic fields.

Above and following spreads: Boots the Chemist described themselves from the early twentieth century as ‘The Photographer’s Chemist’. As a leading British provider of high street developing and printing, they dispensed photographic guidance as well as film services.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

They targeted the “Happy Snapper” sections of the UK, predominantly comprising women interested in capturing family moments. This strategy worked out to their advantage as they tapped into the large customer base of occasional film users and encouraged repeat purchases. Their wallets evolved in style, and their dedication to effective packaging was recognized with awards for design excellence.

At the start of the 1970s, Boots refreshed their photographic wallets with new typefaces and colour schemes, but enduring subject matter – families, animals, leisure – remained.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

A Patriotic Approach Between Competitors

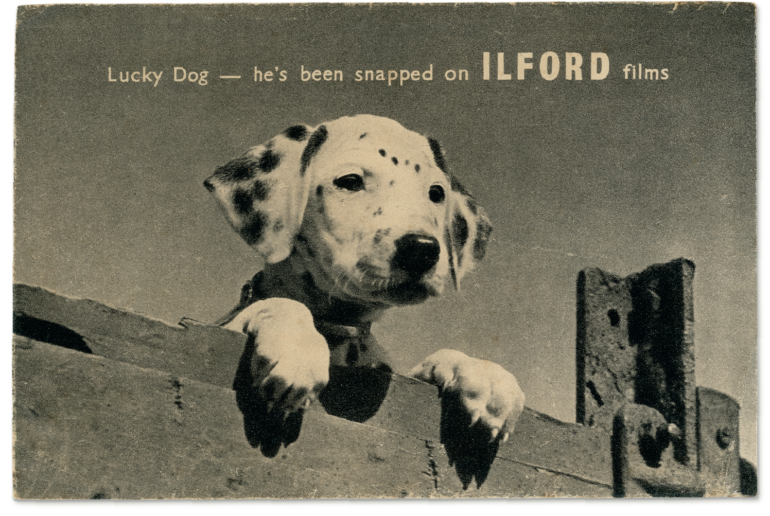

Ilford, known for its film and cameras, marketed its Selo brand as “British-made to suit the British climate.” The Selo brand featured a mascot in a soldier uniform and patriotic advertising materials, emphasizing its British identity. Not to be left out, Ensign film also adopted a national narrative, promoting itself as a “British Film for British People.” Its print wallets featured an energetic design with a character waving a red and blue Ensign banner. German as they were, Agfa would feature English seaside locations on its wallets while advertising in Britain. This highlighted the appeal of British beaches and rural sites as holiday destinations.

A Dalmatian, from the 1950s, is similarly blessed by Ilford film.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

Dr. Pollen’s writing style vividly depicts the rife competition as various brands tried to outdo one another in appealing to photographers. But on the downside, she says that such aggressive rivalry wasn’t without controversy. Print wallets would sometimes depict black figures with stereotypical attributes. This imagery perpetuated imperialist brand names and portrayed cultural superiority. Racialized imagery in print wallets and photographic material perpetuated power relations and reinforced social hierarchies.

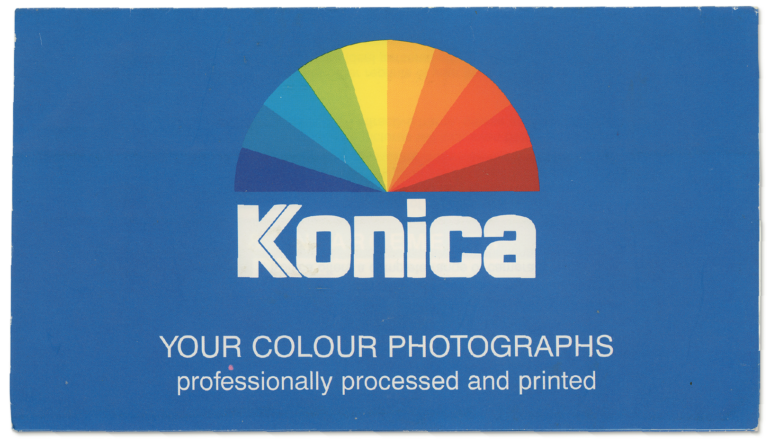

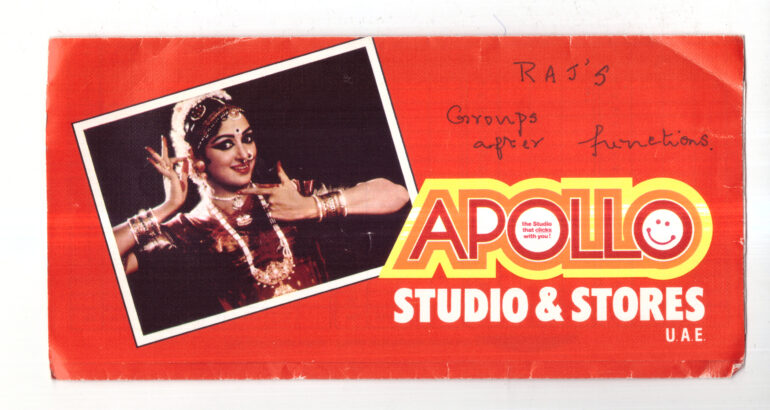

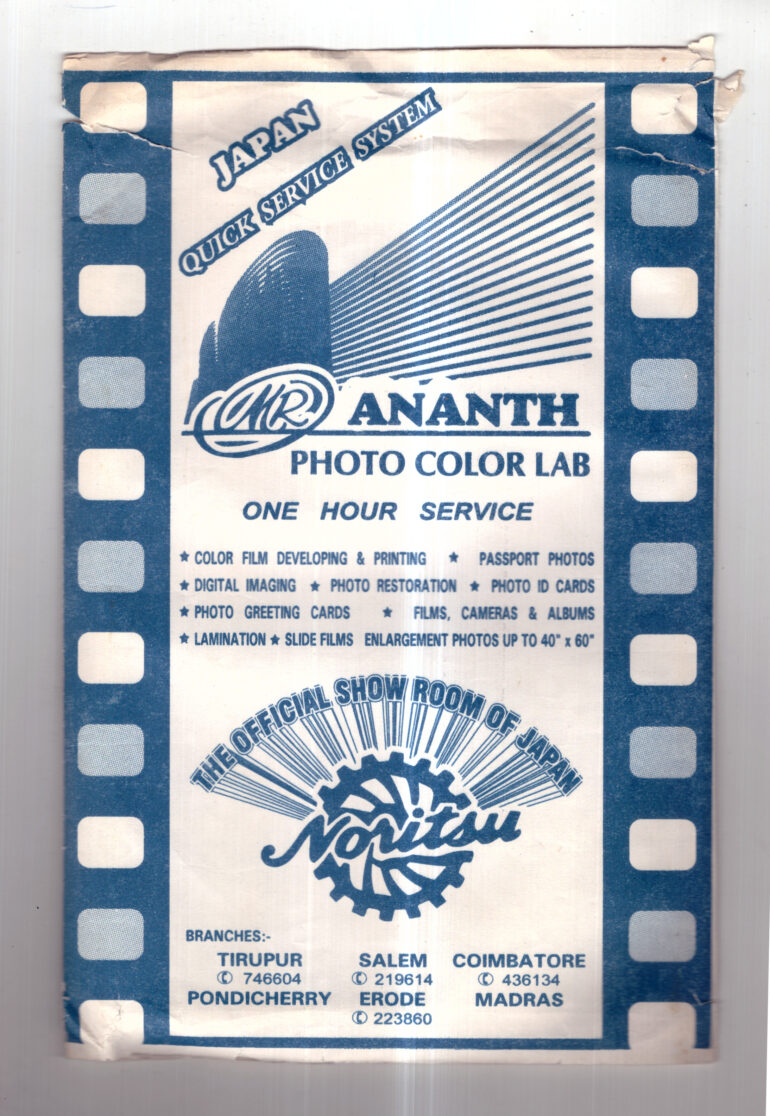

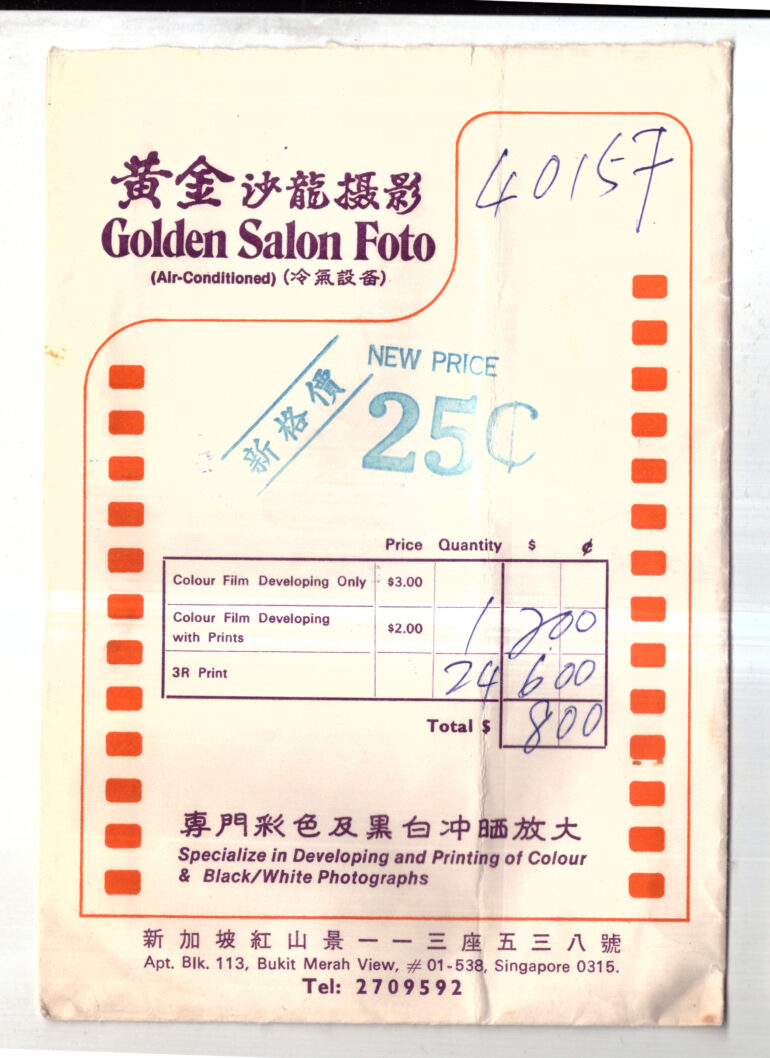

Having grown up with photography in the 80s here in Dubai, we were shielded from such unacceptable imagery. Studios would dispense mostly heavily branded photo wallets while returning your precious negatives. I recall that some places would charge extra for you to get your negatives back. This was a protectionism move to prevent you from going elsewhere for your print needs. Not that Granddad ever left his negatives at any of those places. Thanks to his choice, we now have countless photo wallets at home to open up and digitize for the future.

Photo Wallets Offered Photo Tips Too

Print wallets often provided instructions and guidance to novice photographers, says Dr. Annebella Pollen. Advising against missing opportunities, they sometimes cautioned against including the sky in the frame for good composition and even suggested not breathing to avoid blur. The limitations of box cameras and the limited number of exposures per roll of film often made capturing correctly framed, exposed, and focused photographs challenging. This a far cry from today’s digital era, where it’s often joked that Gen Z snaps more selfies during a visit to the toilet than the astronauts in the Apollo 11 mission took on the moon as a whole.

To keep customers loyal, some photo processing studios offered services that could be considered the predecessors to modern Photoshop tools. Their “finishing” services provide solutions to enhance photographs at a cost, such as adding cloud effects to blank skies.

Ilford wallets from c.1960 show how reviewing prints with partners could be romantic.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

Technical Advancements Led To Shifts In Dynamics

With the increasing popularity of photography and the rise of amateur photographers in the mid-twentieth century, production line development became the norm. To meet the demands of an expanding market, photo-processors recognized the need for convenient services. Mail order and free film offerings became areas for expansion. Companies like Gratispool capitalized on this by offering free films and processing services through distinctive print wallets. By using unique-sized negatives, they created a locked consumer circuit, processing only the films they supplied. This led to strong opposition from traders, and photo-dealers’ associations began to be established.

As print size expanded in the 1980s and 1990s, so too did print wallets. Quality, reliability, speed and care were spelled out through prominent brand names and splashy colour.

Featured in ‘More Than A Snapshot’

The Grunwick strikes in the 1970s brought photo-processing labor issues to light. The strikes involved migrant workers from East Africa who faced long hours, low pay, and poor treatment. The strikes also affected photo-processing operations, with postal boycotts impacting the handling of films and print wallets. Migration also brought new leaders to the British photo-processing industry. Entrepreneurs like Nareshbhai Patel and his brothers founded Colorama, offering next-day processing services. SupaSnaps, launched in 1978, rapidly expanded its high street presence, offering one-hour processing services and incentivizing customers with guarantees and free cameras.

Photo wallets presented a charming and idealized representation of photography. But this tumultuous period in British history shows that there were complex dynamics behind the scenes, including labor disputes and the quick rise of new players. I remember just a handful of places in my childhood where Granddad would develop his film rolls. But by the late 80s or so, film processing technology here in Dubai was about as advanced as anywhere else in the world.

Fading Into Obscurity

As you approach the book’s last few pages, you’ll be reminded of a harsh truth. The advent of digital photography meant that photo wallets started to lose importance. During the late 90s, there were still more than a handful of reputed photo-processing studios in major cities. Back then, film photography, while slowly declining, was still the primary medium to be used. As the shift to digital became more prominent, traditional processing companies struggled to compete with new digital-focused companies that offered printing services from digital uploads or provided online storage and sharing platforms. Dr. Pollen notes that wallets did remain in common use for organizing and storing printed photographs. She highlights the emotional attachment people had to the experience of depositing a film for processing and eagerly anticipating the prints. “Lab coats gave way to laptops,” she notes, and I feel her pain in those words as I read them.

Before we had 24-hour processing or the famed “one-hour photo” development, labs usually took a handful of days to get your prints done. Not because the technology was too slow but often because of how many pending jobs they had. The excitement of opening up those wallets to see the finished prints is something I still haven’t experienced since going fully digital. It’s not that we had goldfish-like memory power back then, that in those few days, we’d forget what we shot. Often it was the anticipation of seeing what the results were like. They were a validation of our photographic skills if they turned out well. If most images turned out wrong, they meant we needed to be more careful with our frames. So that the next time we opened a photo wallet, the percentage of keepers would be a lot more.

Photo Wallets Are Treasures To Me

The shift to digital photography brought convenience and instant gratification. People improve their photography skills much faster these days (and also end up firing unnecessary frames due to this accelerated learning curve). But let’s not forget the loss of the anticipation and emotional connection associated with receiving physical prints. The majority of you reading this article probably don’t print anymore. While digital technology has largely replaced the need for physical images, the nostalgia and appreciation for the rituals and emotions associated with photo wallets remain.

The collection of photo wallets in my household could easily fill a large storage chest. Seeing granddad’s notes on those wallets reminds me of a time when photography was more challenging but also more fun. He wouldn’t just add notes about where the negatives stored inside were tn at. Technical notes would sometimes be scribbled on the outside. I like browsing through them and seeing the names of photo studios from my younger years, where the waft of developing chemicals would hit me as I entered them.

Save Your Photo Wallets, Please

Dr. Annebella Pollen’s book spans a century’s worth of photo wallets that have been painstakingly collected. Her dedication to uncovering the stories behind some of these has to be commended. Whether you grew up with analog photography or not, if you love photographic history, then More Than a Snapshot has many pages for you to lovingly pore over. It brought back many memories for me as I sat with Mom and Aunt to go over some photo wallets from the last 4 decades or so.

USB disks and CD ROMs are effective but visually boring storage media for digital photos. Unlike what we did when we burnt music on CDs, no one really gets creative with CD markers when storing pictures on them. And at best, you’d stick a decal on your hard disk or SSD to decorate it. Photo wallets were both appealing to your eyes and to your soul. And no matter how worn out they get over the years, there’s always a childlike thrill to going through them.