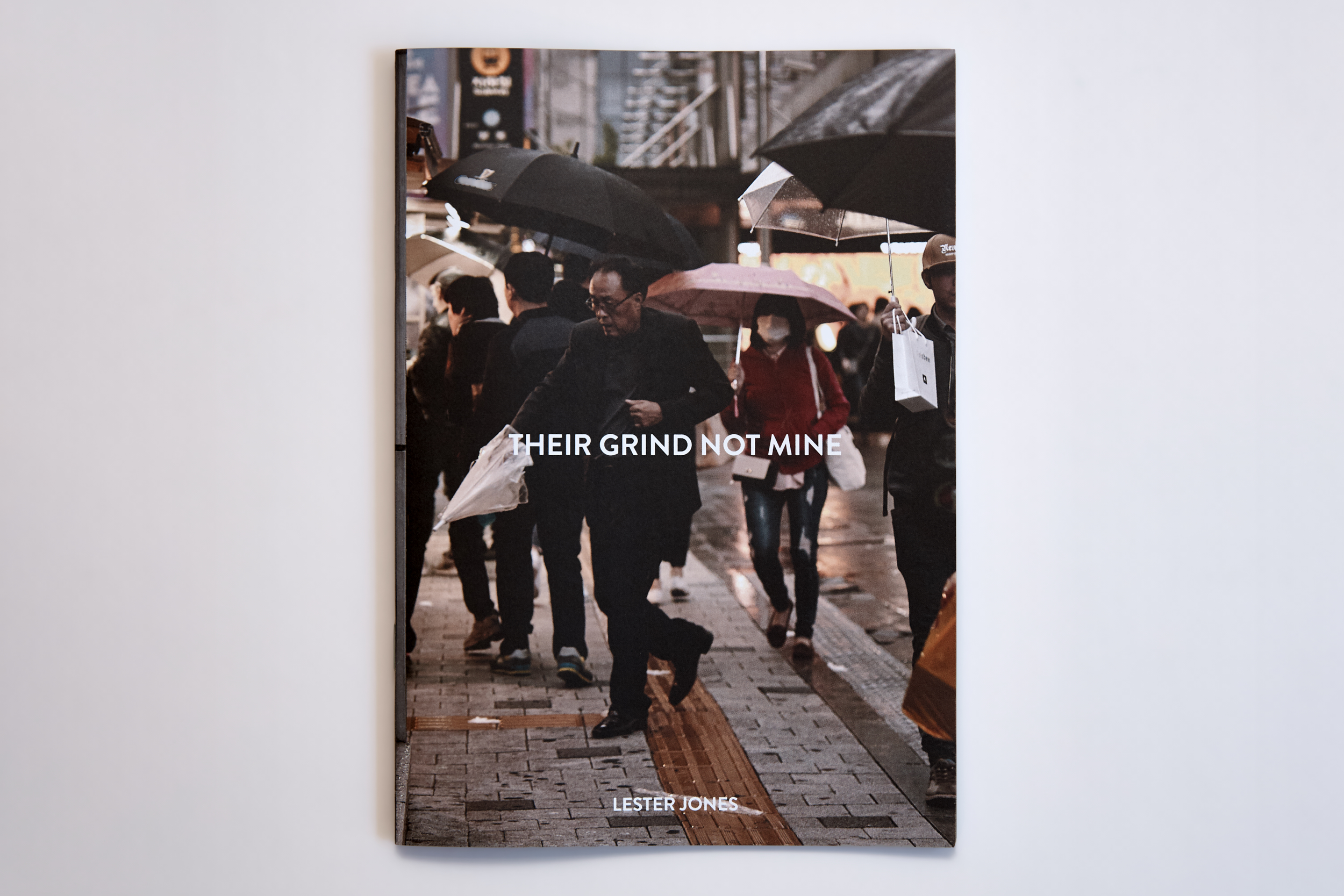

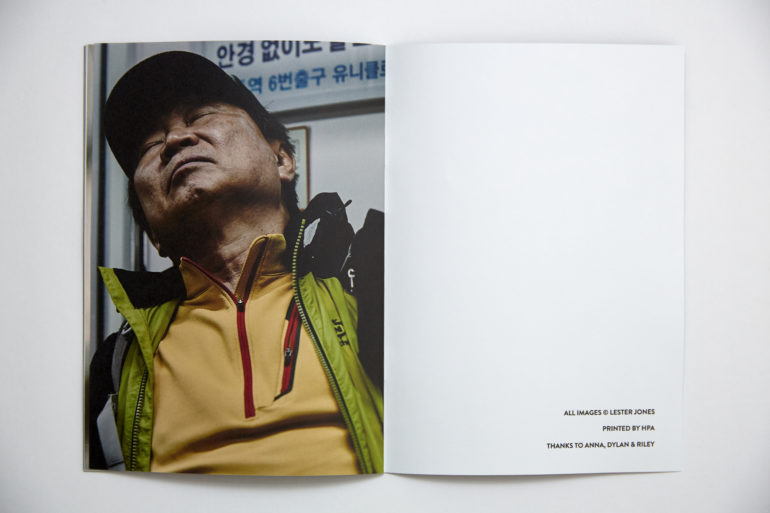

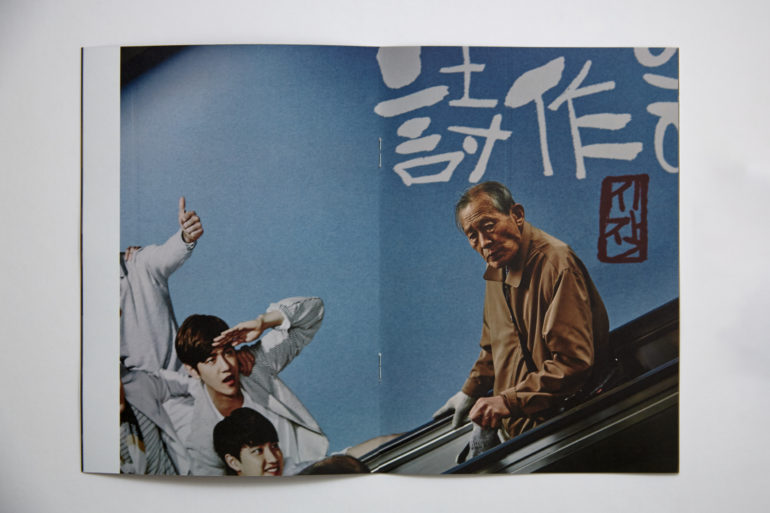

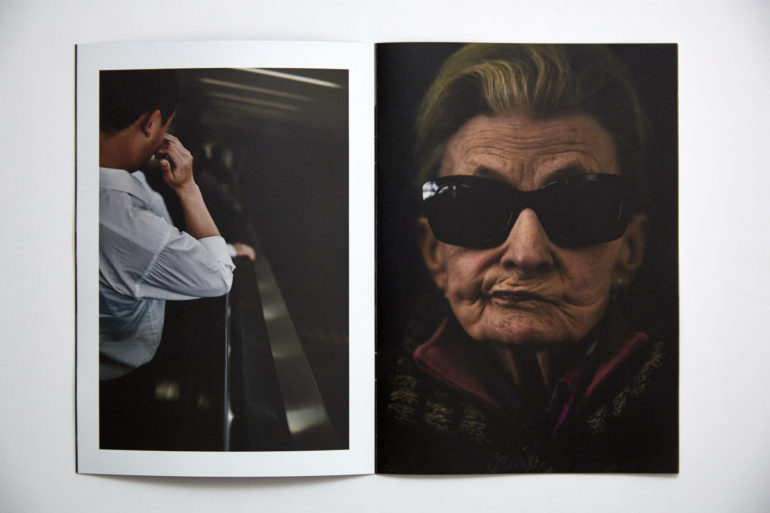

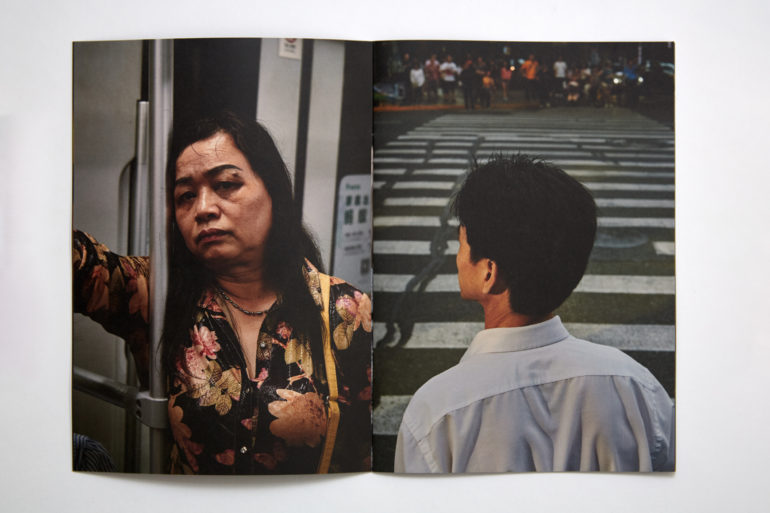

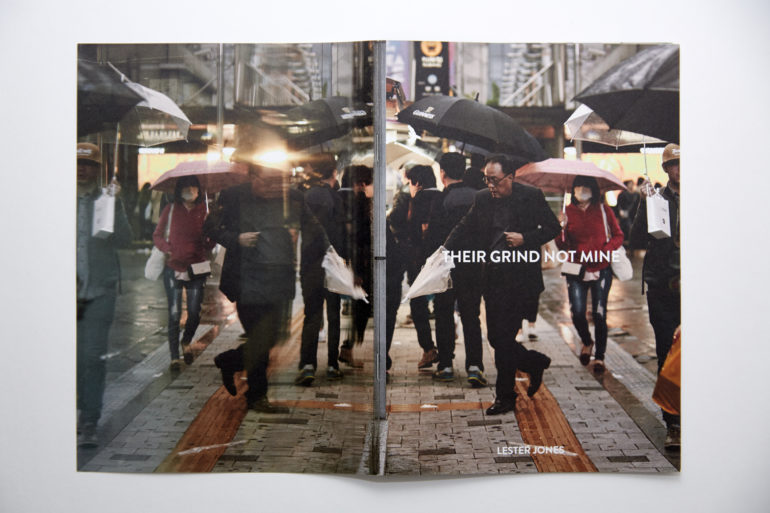

All images of the zine by Lester Jones. Used with permission.

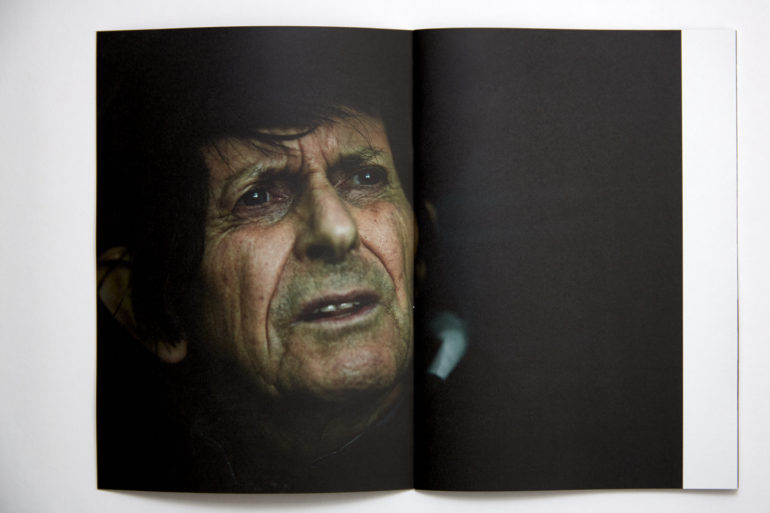

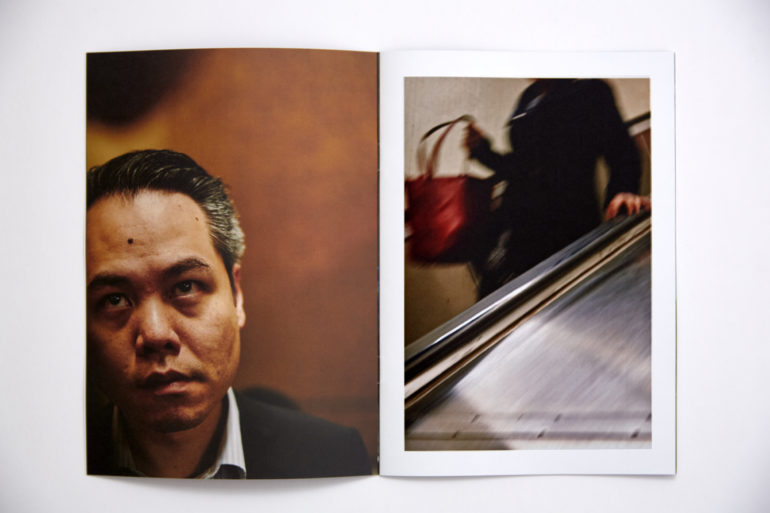

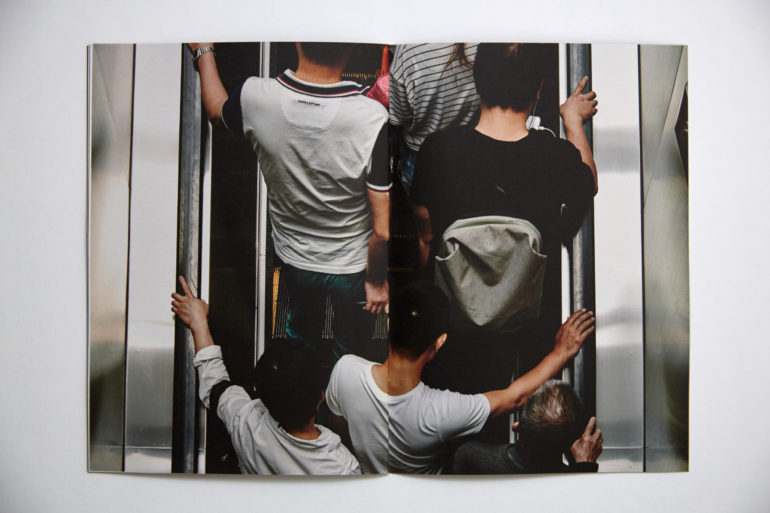

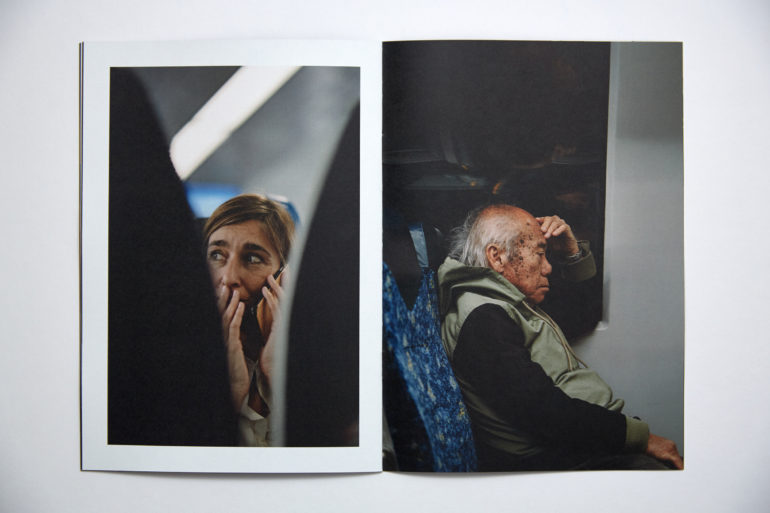

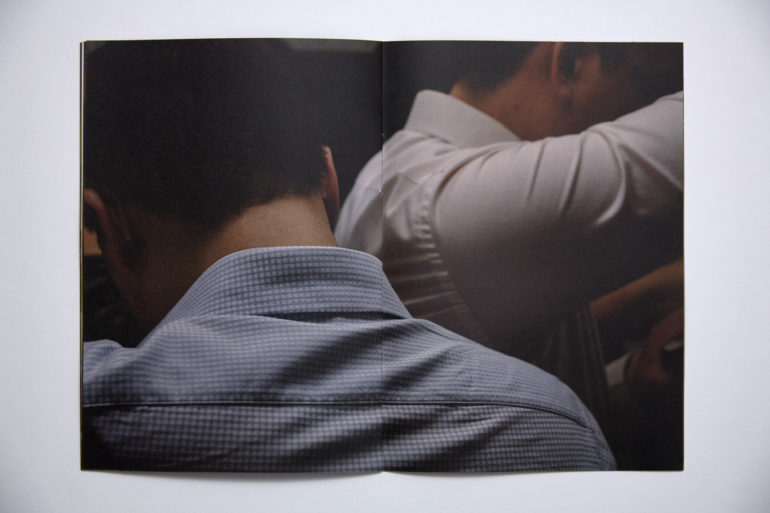

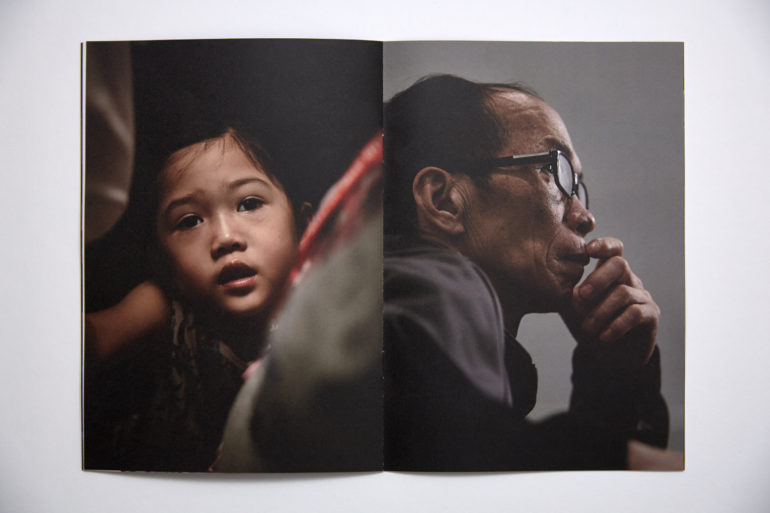

“I shot quick candid portraits and my obsession with documenting this further was born,” said Lester Jones. a photographer who connects to the daily life of the people he lives amongst. His project – and now zine – Their Grind Not Mine, takes a candid look at the mundane, difficult routines people endure. Shot in several major cities around the world, the work looks at the cultures and behaviors of the human form. In this collection of street portraits and street photography, Lester has turned every day, monotonous normalities into something interesting and compelling.

Not only were we interested in the work, but we were keen to find out his approach to his self-published zine. Lester spent some time with us to share his motivations and how he had to be more than a photographer in order to get the published work out there.

Phoblographer: Hey Lester! So how did the idea for the series “Their Grind Not Mine” first come about?

LJ: I am originally from London and grew up with public transport being a necessity within my life there. In fact every morning and night the London tubes, buses and trains are most people’s bookends to their working days as they commute to and from work. That said, while many people need it, there is seemingly a visual level of apathy and malaise from large waves of people you see commuting alongside you. The thought of going to work doesn’t fill too many of us with excitement, and then at the end of the day, tired, drained and fatigued, we often limp aboard to get home again.

“…I don’t want to look or feel like that so can I choose to be empowered and different?”

I moved to Sydney in 2008, and although the beaches and sunshine are a far cry from my life in London, the experience of commuting hit some very similar visual notes with the commuting masses often displaying the same physical signs of dread, fatigue and angst. Then as I traveled to other cities I noticed that this continued.

It was in Sydney about three and a half years ago that I took the first photo for the project though. Standing next to Hyde Park in the heart of Sydney one evening, a bus pulled up and inside were an array of people all displaying signs of stress and exhaustion. I was very close to them as I stood on the pavement looking in, but it wasn’t like I was just looking into the bus, it was like I was somehow looking into those people as well. I saw this as a chance to reflect. This ‘grind’ these people were on, was that the grind I wanted to be on? The answer instantly was no – I don’t want to look or feel like that so can I choose to be empowered and different?

Phoblographer: You describe the project as a “photographic study of the human condition”. Personally, what did you learn from this project?

LJ: I guess we are all susceptible to stress and a desire to escape, and from this project, I try to not get sucked into the vortex of gloom and escaping on my phone. It’s not always easy, but I try and enjoy the journey.

Phoblographer: This was a worldwide project, as you visited many cities around the world. Which cities did you have the most success with the project and which were the most challenging?

LJ: For this project it wasn’t just a case of finding busy train carriages or hectic station vestibules which is something I had seen before, my intention has always been to find intimate moments that showcase something human we can all relate to. I can’t say I found any cities challenging, but in terms of where I went, I was quite selective. The idea of going to New York and Tokyo seemed kind of obvious so I purposely went to low key places to explore the trends more, and within this while Seoul, Shanghai and Hong Kong presented me with some great subjects, London was also a personal favorite.

“…I feel lucky to have stepped out of it slightly to observe…”

Phoblographer: When you document society and the cultures from around the world, thinking about humanity…are we happy?

LJ: I think only we know that. The answer is within us all…right?

Phoblographer: As a photographer, did you feel an observer of the grind, or are you part of it?

LJ: I am of course a part of it, but I feel lucky to have stepped out of it slightly to observe. I would recommend it to anyone, it offers a sense of reflection and I’m not the only one who felt this.

I had an email a while ago from someone who had seen some of the early images and they too saw it as an opportunity to reflect. She was inspired to give up the job she hated as going to work every day filled her with the sense of dread, misery and anxiety seen in the shots. Inspired, she pursued her dream job and became a journalist at a UK paper and since then she hasn’t looked back. Regardless of what the project has done for me, hearing this was incredible.

“…finding restraint and focus was very hard at first…”

Phoblographer: Was the intention to always turn this project into a Zine, or did you have a pivotal moment where you knew you had to turn the work into print?

LJ: From the start this project was just something I was passionate about shooting, and shooting, and shooting. At one point, I was just shooting it for the love of it with no real masterplan. Then late in 2018 after going through the TGNM archives I started thinking about a Zine, and the juxtaposition of creating something physical and visceral that people could hold and read. With so many people immersed on phones and devices on their commute, this idea then grew – maybe people could look at the work in a physical form while commuting! From there the UK photographer, Neil Bedford introduced to the amazing Rachael at HPA Print in the UK and it all happened from there.

Phoblographer: What was the biggest challenge when turning a selection of digital images into a zine?

LJ: Across digital and film I have amassed over 4500 images for this project so finding restraint and focus was very hard at first as I decided on a small publication which would only feature 15 images. The ones that made the cut worked together collectively and individually giving a good variation in locations, sexes, ages, and displays while all having visual intrigue through mood, tone, and composition.

“…it feels great to have created something I have really enjoyed shooting.”

Phoblographer: Are we right in saying you handled all aspects of the zine; from shooting to publishing?

LJ: The project is self-published so in addition to shooting it and making the image selects I also designed the layout, wrote the text, chose fonts etc. In some ways, these other areas were the hardest. I did show a few people initial mockups and sought feedback, and then went from there.

Phoblographer: The zine is finished, it goes out for sale…did you have any moments of “I wish I did this differently,” and how did you manage those thoughts?

LJ: I don’t think it’s healthy to think like that to be honest. I put this out for myself really, as a chance to showcase a passion project that’s far removed from the work I do commercially and editorially, and it feels great to have created something I have really enjoyed shooting.

Phoblographer: Asking you to put your camera down and put your best salesmen suit on…why should people buy this zine?

LJ: Well I could start by saying that I have two kids that I need to feed, you know, really lay on the guilt trip, but I won’t haha. Simply put, I think the project has the potential to communicate something to anyone who looks at it. The feedback on the project and the zine have been incredible with people in the US, Europe and across Asia Pacific getting in touch with amazingly positive compliments.

The zine is really inexpensive, and could help you see your daily commute in a different way, so what have you got to lose?

You can see more details about There Grind Not Mine by visiting Lester’s website.