Last Updated on 05/29/2023 by StateofDigitalPublishing

This is an exclusive guest blog post from Temoor Iqbal. All images by Temoor Iqbal.

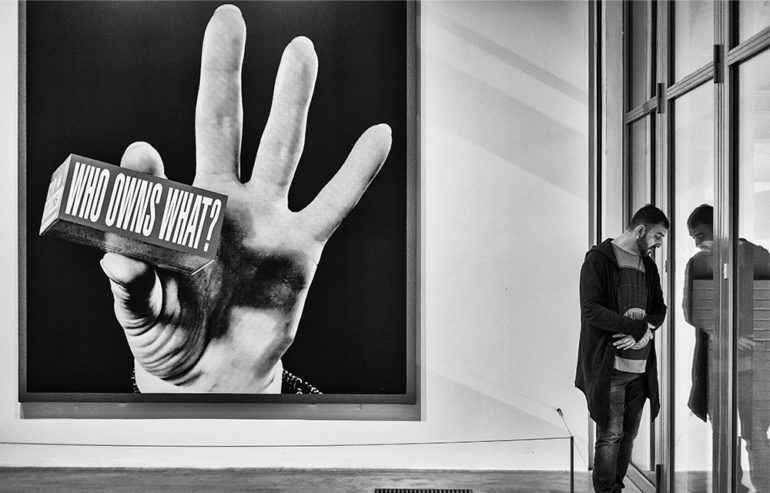

What’s wrong with street photography today? It’s a question of attitude.

The state of contemporary street photography is a common theme in the online photography community, with definitions, styles, and gear exciting great passions. Within this framework, critical evaluation and artistry take second place, as the majority of those discussing street photography are themselves aspiring practitioners, looking to take their own photography to the next level. There’s nothing wrong with this – learning from others is essential in any form of creative expression. That said, the dearth of artistic interest has changed the nature of success in the field – what we now consider to be a good or successful photographer is very different to any point in the past.

So what used to define success? Good photos have always been the key requirement, but there’s also a mindset. Street photography suits introversion – it’s a lonely pursuit, requiring the photographer to enjoy their own company and to appreciate the sensation of being alone in a crowd. The great names of the past devoted long stretches of time to single projects and worked without any thought of publication or fame. Garry Winogrand wouldn’t even see the results of his work for a year, leaving his film undeveloped for that long. Vivien Maier’s work went unpublished during her lifetime, only entering the public domain long after her death.

How does the modern street photographer differ? Nowadays, most people shoot with recognition in mind – success is measured by social media response. In a sense, that’s not a problem – widespread approval has always been a key metric for artistic success. However, there are other things at play in the online street photography community. Followers are required in order for work to be seen in the first place – posting something online actually lacks the democratic openness of, say, putting prints up in a gallery or publishing a book. How do you get followers? A critical requirement is regular posting. Occasional output is anathema to social media – photographers who post every day attract a disproportionate level of attention, as do those who enjoy networking and continuously engage with their followers.

The trouble is, nobody takes even one truly good street photo every single day. Passable, acceptable work can be produced at this rate, but not work that is truly worth sharing. In the days of film, photographers who achieved fame did so by ruthlessly editing their own work, only publicising their best shots. The problem with rewarding the loudest social media voices with our attention is that it encourages the very opposite – the sharing of middling, uninspiring work. In turn, aspiring photographers hungry for quick success see the positive response this gets and set out to produce mediocre work of their own. I won’t name any names – I’m not out to personally attack anyone – but a quick search for ‘street photography’ on Twitter, Instagram, or Flickr will yield hundreds of dull, flat shots of people walking down a pavement, from accounts with thousands of followers. Street photography has become the realm of the extrovert.

Going beyond social media, where does this end up? As with many spheres of life, it becomes an issue of money. We universally accept that the value of a strong social following is the ability to leverage it for a profit. By extension, the ability to make money from street photography has become some sort of holy grail – the mark of true achievement. If someone has made money from their photos, their photos must be the best kind – we’re all guilty of this assumption. Blog posts abound with advice on how to make street photography pay, and those who’ve managed to make money become gurus – cult figures who have transcended the mundane plane of the unremunerated. Curiously, it’s often at the point of monetising that many photographers actually seem to stop shooting altogether, instead continuously reposting old work attached to blog posts on ‘how to make your photography pay!’ and promoting their brand identity.

Live and let live, of course – there’s no value in being bitter, but it’s important to realise what we stand to lose from this mindset. Street photography is a magnificently therapeutic, democratic art form. It’s a way of identifying with the world around you, a way of documenting change and expressing your interpretation of reality. Chasing recognition and a vague goal of making money changes this into a quest to please the crowd rather than to please yourself, and this is a sad loss. Good art comes from within, and if it’s honest and executed with talent, it will be recognised in one way or another (though fame is never guaranteed). In contrast, many of the most popular online street photographers of today are destined to be forgotten – a social media following is a cheap thing that can be lost much more quickly than it is made.

So who is doing it right? The best street photographers around today are those who have, through long practice, developed a consistent style and only post high-quality work. London-based Alan Schaller has moved away from the traditional gritty, grainy street look, making a virtue of incredibly sharp, clean shots that gleam with silver highlights. He has a remarkable ability to capture a chance spotlight on an individual within a crowded scene, and it’s this that gives his work a distinctive, otherworldly feel – a vibe that quickly becomes instantly recognisable, before you’ve even seen the name on the post. The same could be said for the very different work of Schaller’s Street Photography International colleague Walter Rothwell, whose Fuji Neopan 400 film photography is brutally honest, yet at the same time poetic – the best of his travel shots capture moments of uninhibited human (and animal) emotion that stand out for their austere realism. In terms of colour street work, New York photographer Khalik Allah’s iconic street portraits are some of the most visceral, intense examples of the discipline I’ve ever seen – he’s carved out a unique identity both online and in the real world through the bright, rough energy of his photography.

Don’t get me wrong – none of these guys eschew social media, and I have no idea what their financial gains are. What they all do well, though, is choose carefully what they post, and post it for its own merits. This is the antidote to the near-ubiquitous ‘believe in yourself, take my workshops’ attitude that treats street photography as a marketing tool for charged services. Special mention needs to go out here to Eric Kim, who does do workshops, but also makes a huge number of his photos freely available to print and distribute on a creative commons licence, and he gives his articles, blogs, and e-books out for free as open-source material. If more of us had the courage to do this, the photographic world would be a very different place. In any case, this attitude can certainly serve as inspiration to the aspiring street photographer. There’s nothing wrong with sharing your work, but share it for its own sake because you are proud of it and because you believe it to be a true reflection of your abilities, not because you’re hoping to get rich or famous off the back of it. The internet will always be awash with fluff – this isn’t restricted to photography alone – but following these simple principles can only improve the amount of quality work out there, and reduce the quantity of forgettable nonsense.

Ultimately, it’s impossible to fight the tide of change. Art has always had a dichotomy between modish ways of doing things and quiet expertise, and of course it’s rarely as simple a division as I’m making it here for the sake of convenience. The lesson for street photographers is to remember that creativity is a personal thing – take photos for yourself, enjoy the process and find the results that you like. Once you feel confident enough, share only the very best of that work. Some people will like it, most people will ignore it. Accept that and carry on regardless, as you’re not doing it for anyone else’s benefit in the first place. Lose sight of this, however, and it’ll soon stop being fun. Art might become your business, but it’s cynical and sad to force it to be so.