Last Updated on 02/08/2017 by Chris Gampat

All images by Ty Madey. Used with permission.

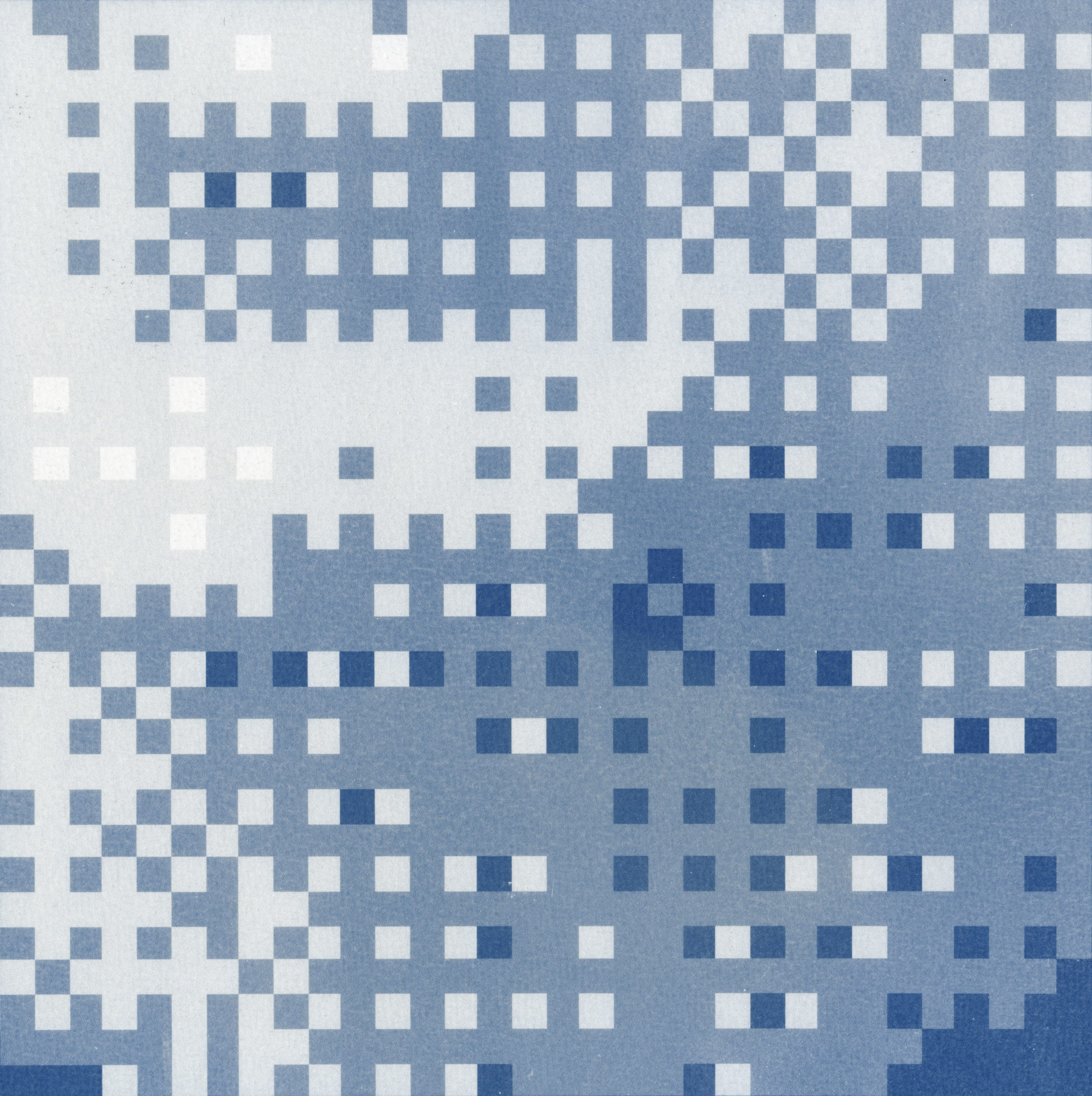

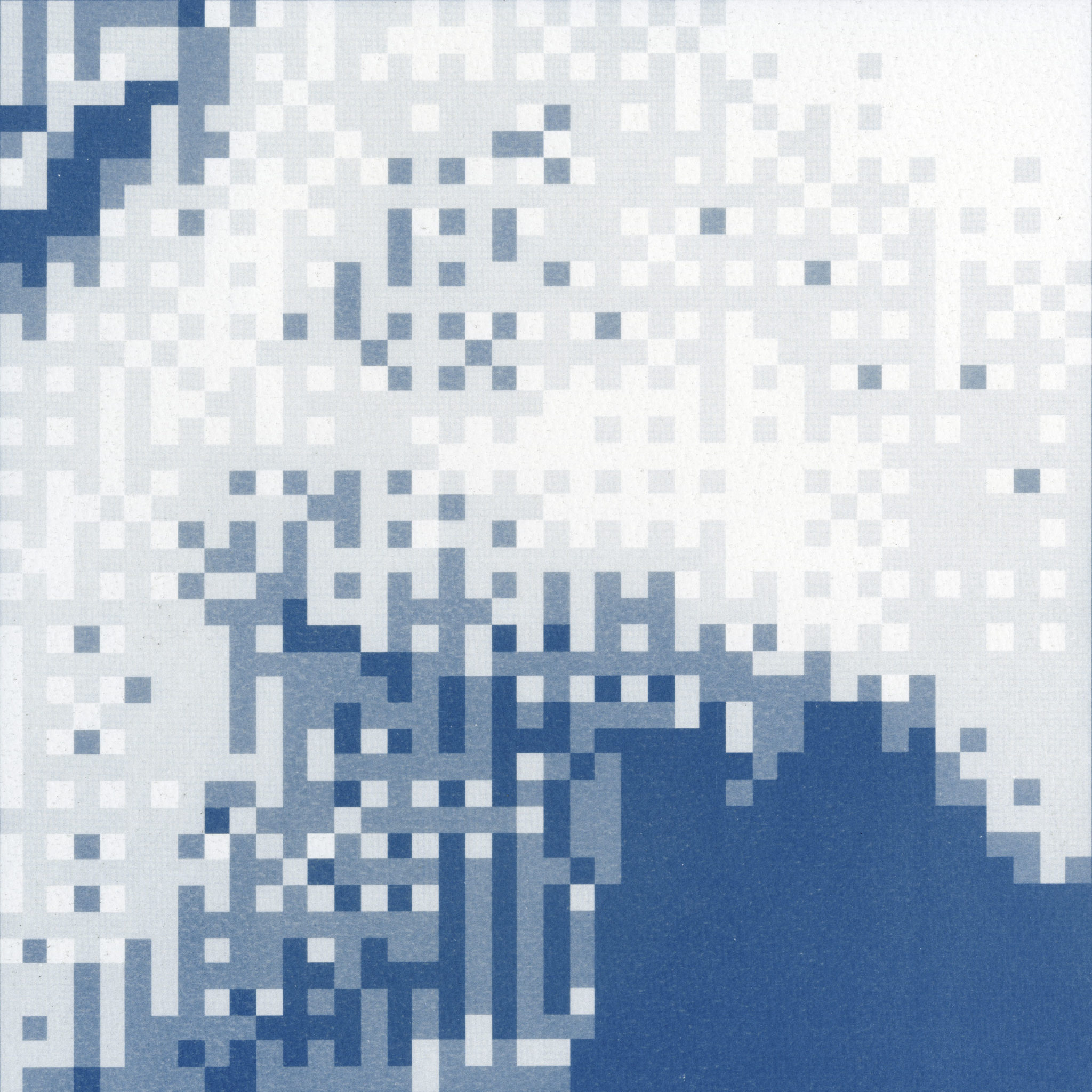

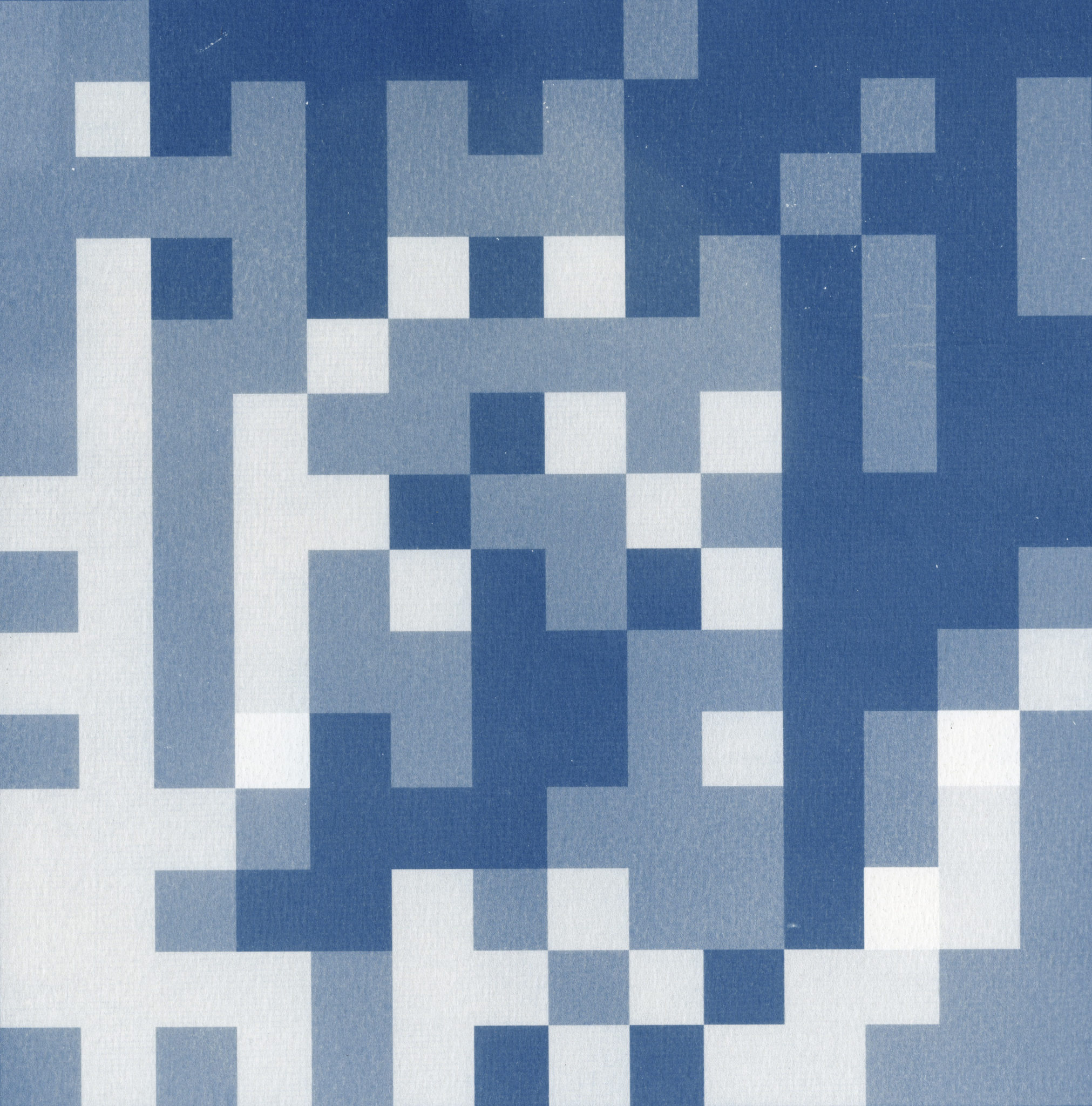

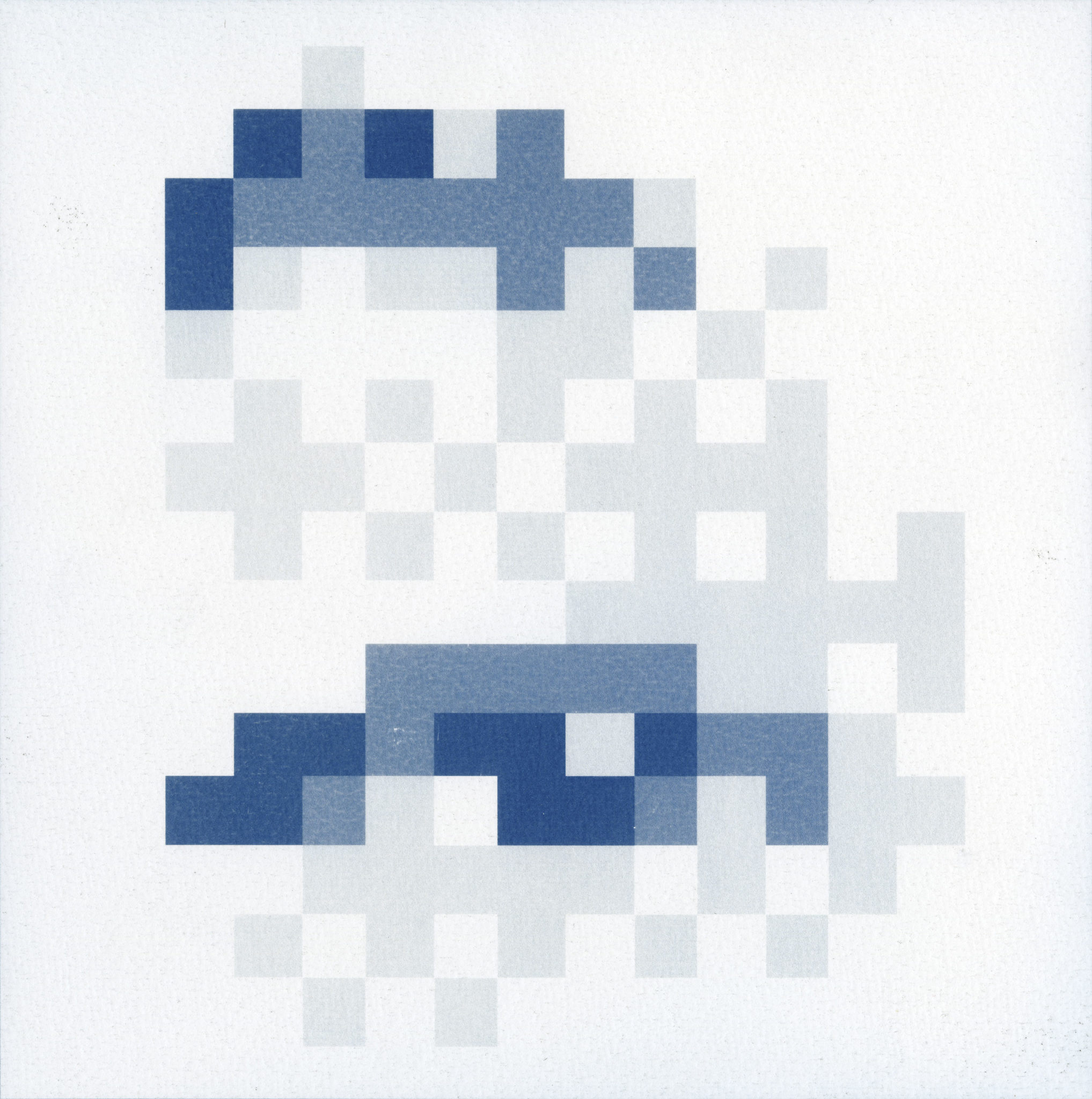

“Pixel Types is a cross section of childhood nostalgia and novelty. I combine my love for the Nintendo Game Boy with one of my current, neophilic passions: Photography.” says Ty Madey in his artist statement for this fascinating project. In a nutshell, the series uses a Game Boy Camera to take photo, enlarge them and ultimately turn them into cyanotype photographs.

Ty Madey is graduating from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in May 2016 with a B.A. in Communication Arts and certificates in Studio Art and Digital Studies. To him, this project was a combination of his love of the stuff from his childhood with his own exploration of art and photography through his studies in college.

“The Game Boy Camera renders extremely pixelated and monotonous images thanks to its 0.1-mexapixel sensor that only has 4 color channels (black, white, and two shades of grey).” the artist statement continues to say. “The result is a deconstruction of each image into a more pure aesthetic form with the individual pixels being highlighted. By combining this look with the cyanotype process, the final product is an examination of the building blocks of the photograph instead of its subject.”

For Ty, the process has been all about portraiture so far.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

Ty: I got into photography in 2012 when I was a freshman in college. I came across a book about film photography and the plastic camera lo-fi movement (lomography) and was instantly intrigued. At the time I didn’t interact with photography beyond basic cell phone snapshots, and the unique aesthetic provided by this type of photography got me hooked. I then got my first camera, a Diana Mini, and ever since have been like a sponge trying to absorb as much information about photography as possible, whether it’s digital, film, or alternative processes.

Phoblographer: What made you want to experiment with alternative processes like using the Game Boy Camera?

Ty: As I previously mentioned, my intrigue for alternative processes and using the Game Boy Camera has its roots in my early interest in the lo-fi movement. While I quickly moved on to shooting with DSLRs, I still hold an appreciation for alternative processes and film. When I was in my film photography class a few semesters back, a graduate student introduced me and my classmates to the cyanotype process.

I was really taken aback by its history and its organic process, introducing chemicals to UV light. After making my first cyanotype print, I felt like I could stare into that Prussian Blue forever; it just had so much depth. And so when I happened upon my old Game Boy Camera that I still had from when I was a kid, I thought that its simplistic 4-color pixelated aesthetic would pair really well with the cyanotype process.

Phoblographer: So what you did here was shot the images with the Game Boy Camera, transferred them to the SD card using BitBoy, put them into Photoshop, intelligently upsized the resolution, and then what did you do? What was the process like and why did you choose to do it?

Ty: I started by taking portraits of my model using the Game Boy Camera. This was a pretty simple one light set-up against a white wall. I knew I wanted the white background to be able to isolate the figure in the image. Then I used the BitBoy to transfer the images to an SD card (which, by the way, has been a true hero in this process).

I then crop out the included Nintendo Game Boy black border that comes attached to the images and enlarge the files using Nearest Neighbor as the resample method. Nearest Neighbor is completely vital in order to preserve the sharp pixelated aesthetic of the Game Boy Camera images. Once I have resized the images, I then invert the colors, flip them horizontally, and print them out on transparent paper in order to create the digital negatives.

The digital negatives are then placed on coated paper (I use Canson Montval watercolor paper) and exposed to UV light. Luckily I have access to a UV exposure unit which has been a real time saver, especially given how weak the winter sun is. As far as why I chose this process, I guess I simply had an idea and wanted to execute it. Before doing this series I had been shooting digital for a while and wanted to experiment with an alternative process to get out of the creative rut I was in.

Phoblographer: How do you think the process added to the final outcome that you have?

Ty: This process has been straightforward and streamlined and has resulted in a lot of predictability in the results. When I get an undesired result, this kind of consistency in the process has made it easy to identify where in the process I made an error in order to easily correct it.

Phoblographer: Using a GameBoy Camera is a bit like combining the Lo-fi way of thinking with the digital world. So what’s that like vs shooting film or shooting digital for you?

Ty: The combination of analogue and digital has really been ideal for me. I have a strong background in both film and digital, and I appreciate both for what they are, but I struggle with preferring one to the other. Combining the digital camera with the cyanotype process has really given me the opportunity to get “hands-on” with the analogue printing process that I adore while being able to take advantage of the cheapness, speed, and ease-of-use of the digital process. I love shooting film, but it is expensive and I think that since I grew up in the digital age I’m often impatient with the time it takes to get the results. So the process in this series was a way for me to try to bridge the gap between my appreciation for both film and digital photography.

Phoblographer: What made you want to shoot just standard portraits like this vs doing street photography, cityscapes, landscapes, etc?

Ty: At my core I am a street photography fanboy, obsessing over Henri Cartier-Bresson and the like, and always dreaming of the day I could afford a Leica. But I learned quickly that getting the kind of results I wanted from street photography wasn’t easy when one doesn’t live in a highly populated metropolitan area.

So I have since turned my focus to portraiture and wanted to experiment with how the highly pixelated results from the Game Boy Camera interact with something so organic in form as the face. Over the course of the series, however, I have moved on from standard portraiture and have instead been using the portraits to crop in and create interesting compositions made from facial features.