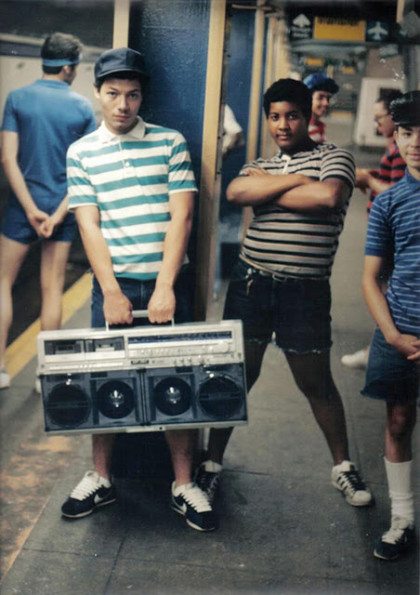

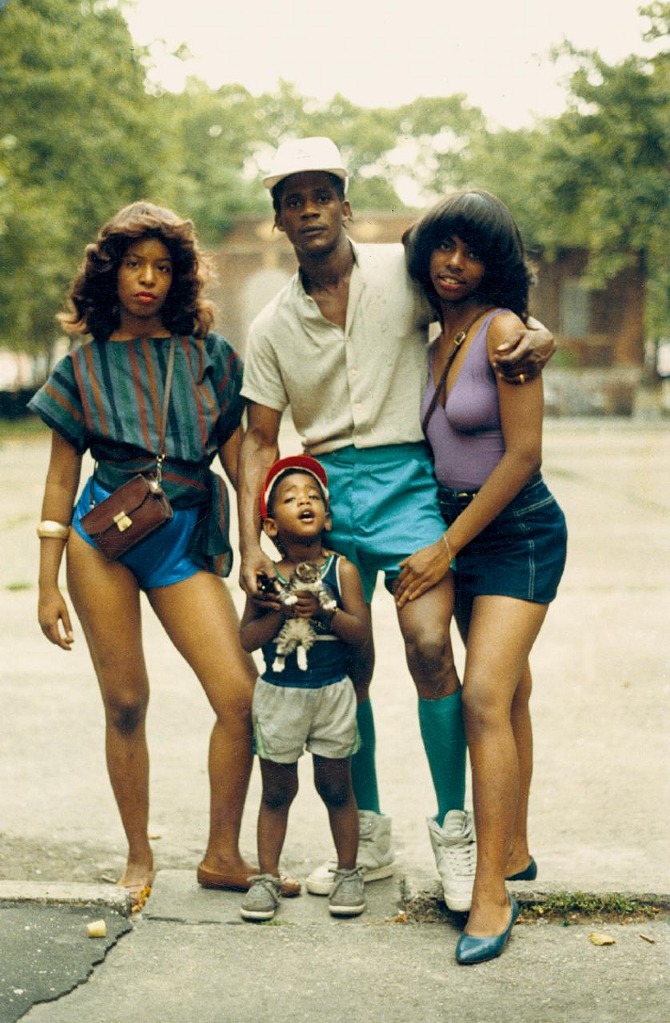

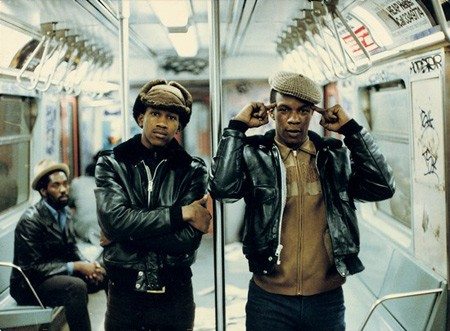

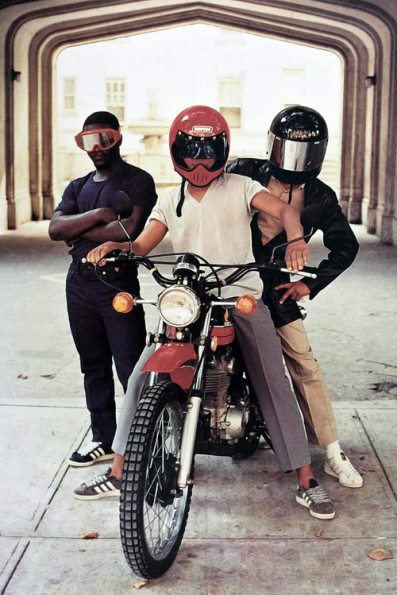

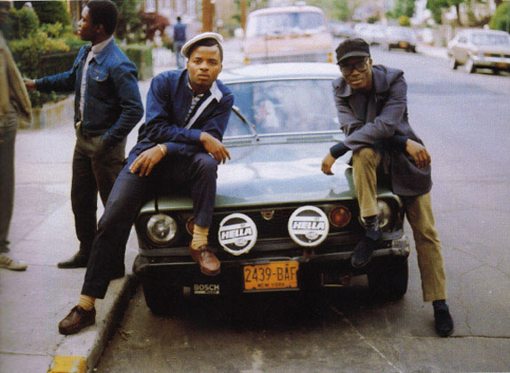

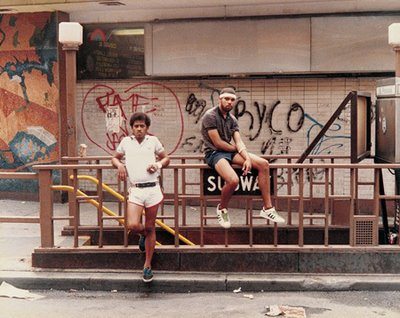

All images shot by Jamel Shabazz. Used with permission.

Jamel Shabazz is one of New York’s most prolific street photographers. Characterized as a fashion shooter, street shooter, portrait shooter, and documentarian, Jamel has been published in galleries, books, magazines, and more all around the world. Growing up in Brooklyn, NY his work in the area earned him a notable spot in the recent documentary, Everybody Street. He even has a documentary about him. Currently, he is putting together a traditional coffee table book of his unpublished black and white images from 1980 to 2010.

We had some time to chat with the street legend about tips, NY life, and developing relationships with your subjects.

Phoblographer: Tell us about how you first fell in love with photography.

Jamel: I first fell in love with photography as a very young child still in my single digits. I think the infatuation came when I picked up my father’s Navy tour books featuring hundreds of beautiful black and white images chronicling his six years aboard the USS Aircraft Carrier Intrepid. He was assigned as one of the ship’s photographers and the photos composed of single portraits and group shots of the various units and personnel stationed aboard the ship. These included high ranking commanding officers, pilots, their support crews, and hundreds of sailors and marines that inhabited this great vessel. In addition to being intrigued with those images, I was equally impressed with the photographs taken during the numerous cities stops that the ship made during its expeditions. I recall seeing scenic and candid photographs from Portugal, Spain, Germany, France, Sweden, and The Netherlands. Viewing these images allowed me to experience my father’s world and bear witness to the power of photography.

Phoblographer: There is a brand new documentary out about you now, did you ever think after all these years of photographing and taking pictures that something like that would happen?

Jamel: To be honest with you, I was not ready for a documentary and in retrospect, I would have declined the offer to participate. Despite my large body of work, I am still a student of the craft, constantly in search of knowledge. I have never been one for the limelight, nor the red carpet. What brings me joy is having my work featured in photography books and exhibited in museums. I am grateful that Charlie Ahearn saw the value in my work and vision to want to document me. The ones who I think are more deserving, in my humble opinion, are the war photographers who put themselves in harms way to show us, who sit comfortably at home, the horrors of war. At this present moment I am still taking it all in and I just hope that my presence in the film reflects a degree of integrity.

Phoblographer: You used to be a correctional officer at Riker’s Island, and that is how you gained the trust of so many troubled youth. For street and documentary photographers that are still trying to break into the business, what are some tips that you can give to relating to your subjects and gaining their trust?

Jamel: It was more about respect than trust, as under those extreme conditions in which I shot, one has to constantly be mindful of manipulation. In conjunction to having a mutual respect, empathy was vital as well. My advice to aspiring documentary photographers is be sincere in your intention, place yourself in your subjects’ position, and for me as a regular practice, I would always carry a small portfolio of my work along with a business card to present, so that they would see that I was sincere.

Phoblographer: As a New York native myself, I believe that we can both agree that many changes have happened over the years as both gentrification happened and the government started to clean up the boroughs. Do you feel that this has thinned out the subject matter that you’ve typically photographed over the years?

Jamel: Sadly, with the crack endemic of the 1980’s many of the communities I documented became war zones. Countless people fell victim to crack addiction from various social and economic positions, the prison industrial complex became big business, and thousands upon thousands were sentenced under the Rockefeller Laws, that gave out mandatory and stiff sentences for crack possession.

With that heavy price to pay, people lost their homes and families were uprooted, as communities that once flourished were under siege. Once the smoke cleared, there were numerous vacant homes and apartment complexes in places like Harlem, Fort Greene, and Bedford Stuyvesant. Realtors seized the opportunity as crime went down in New York and people who were looking to escape the high rents and mortgages in Manhattan and on Long Island, began to inhabit what was once crack infested neighborhoods as ideal places to move to. Today, the average person who once lived in those communities are not able to afford housing in those areas and many are now finding themselves in shelters or living on the streets. The change is very evident to me, because when I travel to those areas today I no longer see people I know and all too often feel like an outsider.

Phoblographer: Tell us about a moment where you were most scared in your photographic career.

Jamel: On September 11, 2001 while standing two blocks north from the World Trade Center minutes after the first plane struck, I stood in awe with my NIKON M90 watching helpless people dangle from windows and many jumping to their deaths. Just when I decided to compose an image of tower one, the second plane hit from the south and I was able to record the impact of the blast as flames and debris engulfed the sky of that once beautiful fall morning. I vividly remember a police officer screaming to bystanders around me, saying” You all better get out of here before you all die.” That is when the reality of the moment hit me and a feeling of uncertainty filled my mind.

Phoblographer: What or what influenced you to be the photographer that you are today?

Jamel: I have to give props to my father for passing on the craft to me at a very young age. It was his great knowledge of the craft and instructions that enhanced my appreciation for photography. In addition, it was the countless photography books that he had in his treasured library that exposed me to the work of Leonard Freed, Edward S Curtis, Gordon Parks, and Eve Arnold. Documentary photographer Joseph Rodriguez also provided me with great insight on how to not only document a community, but also how to tell stories. His prolific book ‘Spanish Harlem’ allowed me to see the power of documentary photography and gave me the notion that my work could also be included in books. I am forever thankful to all of these teachers for helping me to build the foundation on which I stand today.

Phoblographer: Many say that you’ve documented the soul of hip hop culture. Was it ever tough for you to do so and did you ever want to start doing other things at one point or another?

Jamel: I am honored to have been one of the many photographers who have documented the early days of Hip Hop. It was not my intention as I was just looking to communicate with young people on the street and engage them about life, and at the same time learn about them. The photographs were initially intended to be a part of my visual diary as a record of my encounters. Overall my subject matter is vast; youth culture was one only aspect of it, but I have also documented, poverty, homelessness, both active and military veterans, and even ventured into creating a series of fine art images of natural landscapes.

Phoblographer: Tell us about a time where you felt that a subject was really off limits and how you overcame any barriers that were put up to prevent you from photographing that subject.

Jamel: During the early 1980’s, when I was not photographing the local youth in my community, I would venture out during the late night and attempt to document prostitution both in midtown and the Lower East Side of the city. This was far from an easy task, but I was confident I could do it despite the danger. One summer day while walking in an area known for prostitution, I came upon a situation where a prostitute was orally pleasuring a religious figure in his car (I knew him to be such by his traditional clothing and head wear.) Having my camera out and already preset, I raised it and caught them in action. The young lady happened to raise her head up at the very moment I pressed the shutter button and started screaming at me.

The John hit the gas without paying and she was pissed! I proceeded to leave, but was met by approximately five males that were older than I, who came out of nowhere. They surrounded me, each taking on a fighting stance, as I would in response. Shocked by this whole encounter, I had no choice but to try to reason with the one who appeared to be the leader and to my surprise the pimp of the woman who I just photographed. I stated to him in a calm manner that I was documenting prostitution as a project to educate young high school girls of its dangers.

To my amazement he felt my sincerity as his whole facial expression and body language changed. He then said ” I like you! Anytime you want to come out here and shoot, it’s no problem; just mention my name.” I thanked him, and later on I would return to that very same park and document him as well as his women. I would continue to document that particular life for about 10 years, building a very interesting body of images and I was very thankful for having read Dale Carnegie’s book, ” HOW TO WIN FRIENDS AND INFLUENCE PEOPLE”.

Phoblographer: Most of your known work is here in New York, but do you feel that there is somewhere else calling your name?

Jamel: Having grown up during the Vietnam War, I was feed daily images of the war in the evening news. Those faces have never left me, so Vietnam has always been my calling. Since 1980, I have been photographing Vietnam Veterans in New York as well as other cities I have traveled to, so in order to complete my series I feel an urgent need to travel to there to document their veterans from that conflict.

Please Support The Phoblographer

We love to bring you guys the latest and greatest news and gear related stuff. However, we can’t keep doing that unless we have your continued support. If you would like to purchase any of the items mentioned, please do so by clicking our links first and then purchasing the items as we then get a small portion of the sale to help run the website.