Last Updated on 03/31/2020 by Mark Beckenbach

Living Among What’s Left Behind is a project that explores two deeply worrying narratives and combines them into one extremely important story.

“The experience of walking on the top of the floating trash in the Pasig River was shocking,” says Portuguese photojournalist, Mario Cruz. He adds, “But even more shocking was realizing that I was the only one shocked by it.” In 2018, after stepping foot onto the Pasig River in Manila, Philippines, Cruz began to tell a story that focuses on our destruction of the environment and our neglect of humanity. Heavily polluted and transformed into a waste ground, Pasig River was declared biologically dead by the 1990s. It’s no place for human existence. Yet, after being failed by their dreams, a community of settlers has had to call one of the city’s most toxic environments their home.

A World of Extreme Inequality

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, as of 2018, 17.6 million Filipinos lived below the poverty threshold. Unable to meet basic food and non-food needs, life is tough for many families throughout the country. But hardship and a poor quality of life is nothing new for many people living in South East Asia.

As is true for most countries, those searching for a better life turn to the nation’s capital for hope and prosperity. Manila, where you will find lavish malls and high-rise business towers, paints the picture of success. But with further inspection, you’ll soon uncover the gross inequality and the deep struggle for many of the capital’s inhabitants.

Pasig River was once the economic center of Manila. Now, however, it’s a sad example of an uneven society.

“…once I was in Manila I didn’t photograph the communities right away. Instead, I started by visiting the different communities, acknowledging with my own eyes the dimension of the problem. Only after I spent some days visiting them, did I begin the visual documentation.”

– Mario Cruz

After reading about the waves of trash found in homes throughout Manila, Cruz started to investigate the situation with the ambition to document the truth. “I immediately discovered the reality of the Pasig River and the dramatic lives of those who struggle on its banks.” To Cruz, the status of the river and the people that live amongst it was the perfect example of the consequences that come from ignoring basic human needs, and our impact on the environment. But what was also apparent to Cruz was the vicious circle the inhabitants were stuck in. He explains, “the problem of the river and the communities is the pollution. But for most of the families, their income comes from what they can find between the trash in the river.”

Time to Tell the Story

The story in Manila was the perfect fit for Cruz’s desire to focus on social injustice and issues relating to human rights. But to tell such a story – and to tell it well – a photojournalist cannot arrive unprepared. Instead, a story of such magnitude requires careful planning and preparation. Cruz spent four months researching and creating a platform of contacts that would allow him to gain access to the different communities living along the river. He tells The Phoblographer, “it’s important to me to understand really well what I’m about to document.”

Even upon his arrival to the Philippines, Cruz wasn’t ready to spend his time only creating photographs. “Actually, I spent less time taking photographs.” He continues, “once I was in Manila I didn’t photograph the communities right away. Instead, I started by visiting the different communities, acknowledging with my own eyes the dimension of the problem. Only after I spent some days visiting them, did I begin the visual documentation.”

Cruz was overwhelmed by the conditions the community was living in. “The smell is toxic. I had that smell on me until the end of my journey in Manila.” But despite the terrible environment, one that no person from a developed country could imagine living in, Cruz was surprised by the behavior of the people. “Everyone was living their lives so naturally. It was quite sad and disturbing to observe.” To give an idea of what normal life means to the community, Cruz explains that the families have never had a bathroom, no access to clean water, and are deprived of any form of public waste system. Their home, a river that became a waste ground, is now the sewer of the city.

Stunned by the living conditions, we were intrigued to understand the mentality of the local people. Cruz tells us, “It’s difficult to generalize their mood and mentality. I can say that the older generations tend to see the river as a curse and the younger generations are divided between the will to have a better life and the strong likelihood of remaining cloistered in that environment.”

“It’s very easy to create photographs with the purpose of shocking and that is the opposite of what I want to achieve. I want my photography to raise questions and I hope those questions turn into a debate and with some luck that debate can start a change.”

– Mario Cruz

And while it’s easy to imagine a life of constant pain and suffering, thankfully the people are able to find moments of happiness. For example, many of the children who spend their days trying to find recyclable things in the river (so the families can earn money) often play with each other and carry out their tasks smiling as the days go by. And the adults, who live with very little, seem to be able to find some joy in that, something Cruz describes as “truly remarkable.”

Still, there’s no escaping from the fact that this is no life any human should have to live. And as an outsider, a person who’s seen as having a better life, Cruz must be careful in the manner in which he approaches photographing the story. Keeping the dignity of the local people intact is up there with the most important considerations a photojournalist has to make. It’s extremely difficult to ensure you don’t make the people feel like an attraction— a shock story for the developed world to consume and forget about. “It’s very easy to create photographs with the purpose of shocking and that is the opposite of what I want to achieve. I want my photography to raise questions and I hope those questions turn into a debate and with some luck that debate can start a change.”

Moving the conversation to the response of his subjects as he photographed them, Cruz tell us:

“The families that I’ve met and in particular the families with which I spent most of my time with, understood that I could show something that has been ignored for too long. Now that the environmental issues have more space in the media agenda, we tend to see only the superficial part of the problem which in this case is pollution in the river. I wanted to go further and beyond that. I wanted to document the different layers of the problem.”

Faces of the Future

No child should have to work. Youth is a time to develop emotionally, and not have to worry about the strains life will eventually put upon us. The freedom to be young isn’t afforded to the children at Pasig River: they live amongst the garbage and makeshift houses. They have to play a crucial role in the sustainability of the community. As soon as they are old enough to understand, they quickly learn how their families rely on them. “Food is always lacking, the conditions are just terrible and the children survive with this pressure of providing for their families. Even their houses are built with what they can find in the river.”

It’s the day to day experience of the children that made Cruz put them very much at the center of his project. He was devastated to know that the parents of the children he was photographing were born into the same environment — highlighting how, throughout the generations, the problem hasn’t got any better. To Cruz, the children at the river were the unfortunate picture of the continuation of the problem.

But are the problems of pollution and poverty solvable? Is the city past a point of no return? In Cruz’s opinion, “the only solution is relocating all those communities – which is a hard task to say the least.” Although difficult, he does believe relocation of the communities is possible. Rather than moving everyone at once, he feels doing it incrementally is the best way of giving these people a better life. Aside from moving completely, actions can be taken that will improve, if only fractionally, the current living conditions at the river. “Simple measures can be taken. Like for example, installing waste bins in the communities and portable bathrooms managed by the local government.”

Despite what can be done, it’s easy to understand why some of the older generations have given up hope of receiving any upport. They have lived in devastating conditions, raised children in them, and now see their grandchildren growing up in them. What reason do they have to hope? But for the young generation, Cruz tells us, “the students of these communities have goals that are achievable. But from the talks I had with them, I felt that they just wanted to leave their esteros and move to other countries. They don’t seem interested in solving the problem.”

Working in Difficult Conditions

Despite all the preparation that went into the project, because of the pollution and waste, executing it wasn’t easy. “It was a challenge getting into some of the estuaries of the river, called esteros. It’s like walking into mazes,” explains Cruz, adding, “every time you take a turn you never know what you’ll find.” The esteros were initially put in place to stop floods occurring in the city of Manila. However, due to their location, they would become home to thousands of families. “The esteros are no more than piles of unsafe structures carved in extremely polluted waters. Those structures are the homes of many.”

Because he was unable to walk across most of the area, Cruz had to adapt his shooting perspective. He traveled a lot by boat with the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC). This allowed him to photograph the communities from the river’s perspective.

“…photography has an important role in terms of bringing awareness and capturing the evidence that could trigger change.”

– Mario Cruz

But to really grasp the emotion of the story, Cruz had to get closer to the communities. In order to do that, he first had to build trust and become accepted. He had to demonstrate that he did not want to be intrusive, but rather an honorary member of the community, there to tell the world their story. That’s why, to complete this project, he opted to use his Fujifilm X-Pro 2. “For me, the X-Pro series became synonymous with being discreet.”

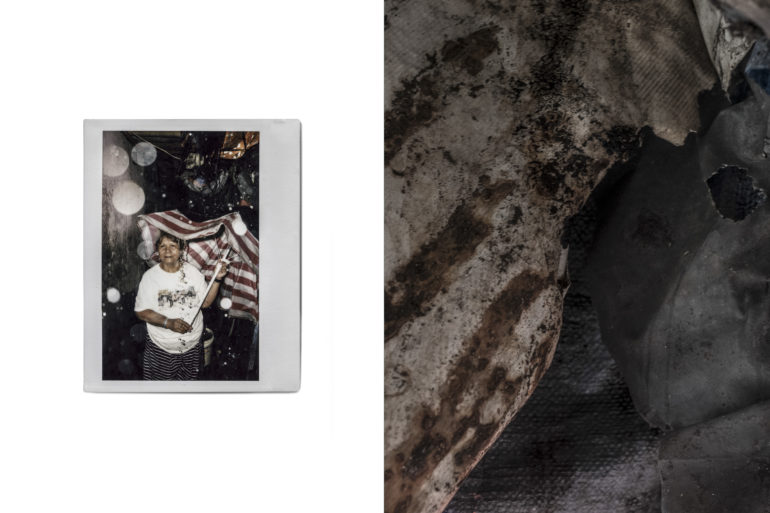

To add an extra layer of diversity to the project, Cruz also carried his Fujifilm Instax Wide Camera. He explains his motivation:

“I decided to use the Fujifilm Instax format to create a series of portraits of the people living in these communities. By doing that, my intention was to highlight them and separate them from the river since most of the time they are almost camouflaged between its pollution.”

With such a vast amount of material to photograph, Cruz has to be prepared to shoot from different angles and viewpoints. Such a task requires the right set up to help him complete his project to the best of his ability. Having multiple perspectives is a core component of good storytelling. That’s why, in Living Among What’s Left Behind, we see a mixture of wide angles, tight frames, and portraits coming together to send one clear message.

As well as having a reliable camera, you need a range of lenses that match the technical ability of the photographer. For Cruz, it’s all about using the prime lenses. He prefers them over a zoom lens, as they encourage him to move and help him create the flow of his narrative. For the project, Cruz paired his X-Pro 2 with the Fujifilm XF 18mm f2 R, the Fujifilm XF 23mm f2 R, and the Fujifilm XF 35mm f2 R.

“I use different lenses because for me it’s important to have a dynamic in the story otherwise it can get very repetitive and in terms of photography I like to explore different aspects of the same subject so in a way it’s always an exercise of processing each part of the story and the different approaches I take is part of that process.”

The Life of a Photojournalist

From the moment he was born, Cruz was no stranger to photography. His father was also a photographer, so for as long as he can remember, he had always been around cameras and creativity. At first, however, it seemed as though he did not share the same interest as his father. Sure he took notice, but he showed no signs of following the same career path. By the time he reached his mid-teens, his attention started to change and photography became a way of expressing himself.

When he was 18, he decided to study photojournalism: a path he was sure he wanted to follow. Photographers like James Nachtwey were his inspiration. By studying the masters, he understood the power behind photography. In his words, “photography has an important role in terms of bringing awareness and capturing the evidence that could trigger change.”

Years later, it’s clear Cruz still has the same passion and desire to show the world its most important stories. He sees photography as a unique power. It’s a medium that has the ability to bring awareness to a situation and focus attention on a subject that has otherwise been ignored. “In every project my goal is the same: scream through photography. It’s like an alert. Sometimes it works.”

Taking Care of Mental Health

An often overlooked aspect of being a photojournalist is the impact it has on mental health. In the case of Living Among What’s Left Behind, seeing communities in such extreme poverty isn’t something you just go home and forget about. He opens up, “while I was in Manila it wasn’t easy to manage all that I was witnessing, especially because I was seeing so many children struggling in those conditions. It really puts everything in perspective.”

“It was extremely painful to witness the conditions in which they live, the way they are isolated from the world. It was like experiencing something that should not exist.

– Mario Cruz

But when you find yourself far away from both your home and your family, it’s the little things that help you get through. “I shared some very emotional moments with different families (in Manila).” Cruz recalls one of the more emotional moments that stuck with him from his time in Manila:

“The Fontalba family lives in Magdalena, the worst example of what’s happening in Manila. A member of that family is Jose Fontalba, who has cerebral paralysis. Due to his condition, he gets a lot of diseases from his relatives who go into the water of Pasig River. But unlike them, it is extremely hard for him to get immune or even healed too many of the serious health episodes that run inside the family.”

“It was extremely painful to witness the conditions in which they live, the way they are isolated from the world. It was like experiencing something that should not exist. I want to believe that my work is in a way a resemblance of that, an unpleasant journey but a very necessary one. That family opened their lives to me and I’m thankful for that.”

A Young Man Struggling to Survive

Now back home, able to see the Tagus River from his home in Portugal, Cruz is in a better position to reflect. “I often remember the Pasig River and those who are trapped in its pollution. Every project helps me to evolve in different ways: the Pasig River was an alert that I wanted to create but naturally became an alert to myself.”

It is at the point of reflection that Cruz shares one encounter that will always stay with him. While in Baseco, the port area of Manila, he was introduced to a young man named Nolito. At the time of meeting, Nolito was 19 years old. He had been living and working in the Pasig River since he was three. After years of working in a polluted environment, Nolito’s lungs have become obstructed. Cruz opens up:

“He needed to receive oxygen 24-hours a day for at least a year and the cost of that treatment was $300 per month. We talked a lot about his life and how he ended in that situation. I asked his parents how they could afford that treatment and they told me that they had to sell everything they had including the floor of their improvised home, loan money from neighbors but it was still not enough.”

“When I asked Nolito what he expected for his future he just said that he was counting the days to get back to the river because he knew his parents were facing serious problems to the point of not having enough food for all of them”

Cruz quickly notified the PRRC about Nolito’s situation. Thankfully they were able to support him with paying for his treatment. But sadly it was only a matter of time before Nolito would have to return to Pasig River and continue living and working there.

The Importance of Visual Storytelling

Without hardworking photojournalists like Cruz, many of the stories the world sees may never be told. But spreading the message is only one part of the solution. There are things we, the viewer, can do to fight for the causes that matter. When his work is seen worldwide, there’s one thing Cruz would like the audience to be aware of. “You are not directly responsible for the pollution in the Pasig River but you are now responsible for sharing what you just saw.”

As individuals, it’s extremely difficult to drive change, but as a group we can ensure that those who need to act start to listen. That’s why photojournalism is so important. It can reach a mass audience and encourage us to shout louder about the inequality we see amongst society.

The photographs from Living Among What’s Left Behind speak for themselves. There’s no denying the seriousness of the situation. But in closing, we asked Cruz to put the message he would like the world to see into words:

“What I photographed is often described as a dark projection for our future environment but in fact, what I photographed is the present and the past for millions in Manila. The Pasig River contributes with 63,700 tons of plastic deposited into the ocean each year. It’s not a local problem. It’s global. It’s not in a distant future, it’s happening now. The communities and the river can no longer be ignored. Use the evidence in the best way possible.”

About Mario Cruz

See more from Mario at his website

1987, IN LISBON, PORTUGAL.

MARIO CRUZ IS AN INDEPENDENT PHOTOGRAPHER FOCUSED ON SOCIAL INJUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES.

HIS PROJECTS HAVE BEEN RECOGNIZED WORLDWIDE.

“RECENT BLINDNESS” – ESTACAO IMAGEM 2014 AWARD

“ROOF” – MAGNUM 30 UNDER 30 AWARD

“TALIBES: MODERN DAY SLAVES” – WORLD PRESS PHOTO 2016, PICTURE OF THE YEAR 2016, MAGNUM PHOTOGRAPHY AWARDS 2016, ESTACAO IMAGEM AWARD 2016.

“LIVING AMONG WHAT’S LEFT BEHIND” – WORLD PRESS PHOTO 2019.

HIS WORK HAS BEEN PUBLISHED IN NEWSWEEK, INTERNATIONAL NEW YORK TIMES, WASHINGTON POST, CNN, EL PAIS, CTXT AND NEUE ZURCHER ZEITUNG.

HE’S THE AUTHOR OF TWO BOOKS:

TALIBES MODERN DAY SLAVES, FOTOEVIDENCE, 2016

Editor’s Note: This is a sponsored blog post from Fujifilm.

About FUJIFILM North America Corporation (Fujifilm)

FUJIFILM North America Corporation (Fujifilm) is empowering photographers and filmmakers everywhere to build their legacies through sharing their stories. Grounded in its 85-year history of manufacturing photographic and cinema film, pioneering technologies in lenses and coatings, and driving innovation in developing mirrorless digital camera technologies, Fujifilm continues to be at the center of every storyteller’s creative vision.

Pushing boundaries in digital photography and filmmaking innovations, Fujifilm’s X Series and GFX family of mirrorless digital cameras and FUJINON lenses yield exceptional image quality for creators of all levels. Offering image clarity, advanced color reproduction technologies and a wide range of film simulations, Fujifilm’s family of mirrorless digital cameras delivers on fulfilling their intrinsic mission of capturing and preserving moments for generations to come.

With a Fujifilm digital camera at your fingertips, you can seize the moment, share your story and build your legacy. Learn more on our website.

Like us on follow us on subscribe on and join the conversation on Facebook, like us on Instagram, subscribe on YouTube and join the conversation on Twitter.

What momentum do you want to start?

It’s amazing how a single thought, action or personal passion can ignite something that can make a difference. As a fellow photographer, we invite you to share what drives you… what do you want to get started, build momentum to? It starts with you. Share your visual social stories with #visualmomentum.