Last Updated on 05/09/2019 by Mark Beckenbach

All images by Alyssa Meadows. Used with permission.

”…very rarely are the brave women who speak out doing so with any expectation of reparations – we know the odds are against us.” These are the worrying words of Alyssa Meadows as she opens up about victims of sexual violence. After almost a decade working as a photographer, all whilst being deeply concerned about women’s issues, Alyssa has been able to bring the two elements together. Her project, Every Woman I Know, takes a brave and honest look at the range of examples of sexual violence women have experienced. In this portrait series are women Alyssa knows personally. And whilst they share their story, she also shares hers. Through public and anonymous portraits, and with the use of the written word, she has created a photography project that aims to educate and give a safe space for others who may wish to come forward and discuss their experience. Two years after starting it, we spoke to Alyssa to learn more about this ongoing series.

Phoblographer: This is your most recent project. Where did the idea come from and why is now the right time to do it?

AM: Well, I actually conceptualized the project probably two and half years ago and solidified the concept right after the results of the 2016 Presidential Election. I had already been an advocate for women’s issues for almost a decade, and been working as a photographer for just as long, but had never found the right way to fuse the two passions together in an artistic endeavor. After the campaign, it was like the two circles of this Venn diagram magnetically smashed together to almost completely overlap, and this is now just the first of three projects focused on the topic, with more ideas constantly developing. The #MeToo movement (which is actually a resurgence, if we’d more widely recognize Tarana Burke as the original founder of the movement back in 2006) actually blew up about 9 months into developing the project, and I realized the world was more ready for the project than I had previously given it credit for. Since then, I’ve been moving as full steam ahead on the project as I can.

Phoblographer: In the images is a self-portrait. If comfortable, please can you share your own experience with sexual violence?

AM: Unfortunately, I have recently felt the need to be careful about how much I share regarding my own experience due to veiled threats made by my attacker through social media. I do not want to allow someone who already violated me so deeply another opportunity to do the same in a different way (as we saw with Christine Blasey Ford, the chances are our attackers will face no repercussions while we undergo self-inflicted character assassination). I’ve recently been made aware that my own attacker is now trying to spin the events of that night entirely and claim I attacked him. This just speaks to how we as women are not ever really done with the fear and anxiety of our experience once it’s physically and chronologically over.

We continue to live under the threat of additional attack and violation; that we’ll be blamed for our own victimization, that the police won’t believe us (as was actually the case with one of the women in the project), or that coming forward will bring with it retaliation (the burning down of Roy Moore’s accuser’s home or the suspicious burning of one of the victim’s homes in the Netflix documentary Audrey and Daisy echoes terrifyingly real when you know your own attacker knows where you live) in a myriad of potential ways. On top of that, there’s also the very real threat of the police actually charging you with a false allegation, which I’ve seen happen firsthand in my hometown. My experience was now almost eight years ago – the ramifications of it are ongoing and never-ending, and that’s what makes it such a heinous violation of another human. We as a society all too often fail to recognize that.

“So much of our society puts the responsibility on the person who’s been violated, for their own failures to protect themselves…”

When these are the risks we face in the mere act of coming forward and speaking our truths, it’s hard to say how much is too much, and what amount puts us at risk. That’s why I’ll never exhibit the public portraits of the participants next to their stories – while I’m comfortable sharing my story in the handwritten nature of the project, I recognize myself how uneasy I feel at the thought of my story next to my public-facing portrait, and know many of the participants I’ve photographed so far feel the same way.

Phoblographer: If at all, how do you feel that experience shaped your direction as a photographer?

AM: I think my knowledge base about the topic has shaped my direction more than my own personal experience has. Running a fairly popular blog on intersectional feminism has deeply educated me on how to address, handle, and educate people on sexual assault. I’ve written posts about how to speak to survivors, how to avoid victim blaming and slut shaming, how to remind them they did nothing to deserve it, that it wasn’t their fault. So much of our society puts the responsibility on the person who’s been violated, for their own failures to protect themselves, like they’ve somehow done something to deserve what someone else has done to them in such a horrible way. Understanding that reality, the need for the project, the statistics that this body of work can highlight in a real-world application? That all comes from being a passionate advocate for women’s rights, not from being a victim myself.

“That being said, I also know that my experience helps fuel my activism so if we look at it from that lens, I think we can say it contributes.”

Honestly, though, I think a past relationship that was emotionally abusive was just as much, if not more so a factor than my past experiences with sexual assault, and we often forget how serious of an issue that is as well.

Phoblographer: You describe yourself as “being the sponge,” having to soak in all these stories. That must be mentally taxing; how do you handle that and what do you do if it gets too much?

AM: I go hike. I hide in nature, I detox and wring myself out in the woods, squeezing out all the hurt, all the emotion, all the heartache and pain I feel for the women in my life who’ve unfortunately shared in this all too common experience. I’m actually pretty mentally resilient, and I’ve been an advocate for the injustice regarding this so long, I’m always half-prepared for what I’m hearing, as painful as it might be to absorb. I love being able to be the open arms and ears, the safe space that allows them to speak their stories out loud, some of whom are doing so for the first time, and I will always happily embrace the opportunity to be that for the women in my world around me. The cost of that openness is I often need to isolate and escape from humanity entirely so that I can let it all go, drain it all out, and then come back to start soaking up these stories all over again. I’m not sure if that makes sense, but it’s the best way I know how to describe the process, and the ebb and flow of the project. I’ll often dedicate a month or two to shooting, then step away again for a few weeks to a month to let it all out again.

“The statistic is one in three to one in five (depending on the year, this number fluctuates) women will experience sexual assault in their lifetimes.”

Phoblographer: The project includes visible portraits and portraits where the subject’s identity is protected. How do you think the impact of a personal story differs depending on which kind of portrait they choose to have?

AM: I don’t think it does. Each participant’s story is their story, regardless of whether or not you see their face, and their story is never shown with their face. The impact is in their experience, which is shared through their words alone, and in your taking the time to read them, or by seeing the look in their eyes with the public portraits. The silhouettes were intended to provide a safe way to participate anonymously (as I knew many women would want the security of that option), and also make you question “is that someone I know?” because we so easily forget to extrapolate the statistics to our own personal bubbles. The statistic is one in three to one in five (depending on the year, this number fluctuates) women will experience sexual assault in their lifetimes. We all easily know 300, 500 women, but fail to really recognize that means we all statistically know at least 100 women who have been violated, experienced sexual violence, and that we really need to recognize the ugly, undeniable severity of this issue. We as a culture are quick to dismiss the pervasiveness of this pandemic, and I hope my project can help highlight that.

Phoblographer: Are you able to share the reasons why some women choose to remain anonymous?

AM: Most boiled down in one way or another to fear of retaliation. One family member lamented to me an intense fear of being unable to ever return to her hometown due to the powerful positions held by her attackers there should she come forward. Another friend wanted to participate, but her own husband is still unaware of her past experience and she does not want to share that yet. One woman’s whole community knows and she speaks about her experience very openly, but to her, that’s still not the same thing as telling ‘the whole wide world.” Other women have said they are fine with their public portraits being shown in print exhibitions, but not on the web. It’s really a case by case basis. I provide every woman the opportunity to take a public facing portrait that I let sit in the archive if they’re on the fence about whether or not to stay anonymous – some women have decided to have me lock it away in my archive, while others have opted to come forward as circumstances in their own lives shift and change. I’ve also had participants withdraw from the project entirely – my biggest priority is respecting the wishes and feelings of the participants that have trusted me with their stories for this project.

Phoblographer: What was your thought process in terms of the aesthetic of the public portraits? The style you chose; how do you feel that fits in with the topic of your project?

AM: The thought process I had was to show these women as the brave, bold beautiful badasses I see them to be. I wanted to have the portraits lit in a way that would show them the way I see them (glorious goddesses) that would also be an easy shift to change from the silhouette lighting to the public portrait lighting. Absolutely nothing changes except the addition of a front-facing octa and a reflector, and that choice was both for ease of shooting without an assistant as well as creating powerful, flattering lighting.

Phoblographer: Moving to shoots. How did you build trust with your subjects and get them in a comfortable mindset in order to take their portraits?

AM: I think this project would be manifesting very differently if it were not focused on women I personally know. Most of these women have known me for years, if not decades – they’ve been reading my angry facebook rants, seen the dozens of articles I’ve shared about rapists that faced little or no repercussions, the stands I’ve taken for advocating for women’s issues. I believe a large part of my community associates me with this kind of activity, and subsequently know I am also their advocate, that I will listen without judgement and hear their story objectively, that I will not blame or shame them for their experience. I think essentially I’ve already established a sense of safety and security before they even step foot in the studio – they know me and what I’m about, and that my first priority is always to take on what’s wrong with our world as proactively and productively as I can.

I also make everything about the project opt-in besides the anonymous portrait and handwritten personal account. When I give participants the questionnaire, I tell them they don’t have to answer any questions they aren’t comfortable answering, and I ask all the participants if they opt in to behind-the-scenes, recording audio, and the public portrait. Knowing that every component is something they have the freedom to either take on or reject I think is very empowering and comfort-inducing.

Phoblographer: At this point in the project there are 29 portraits. Without linking them to the subject (unless you’re able to), are you able to give us a range of the types of sexual violence they experienced?

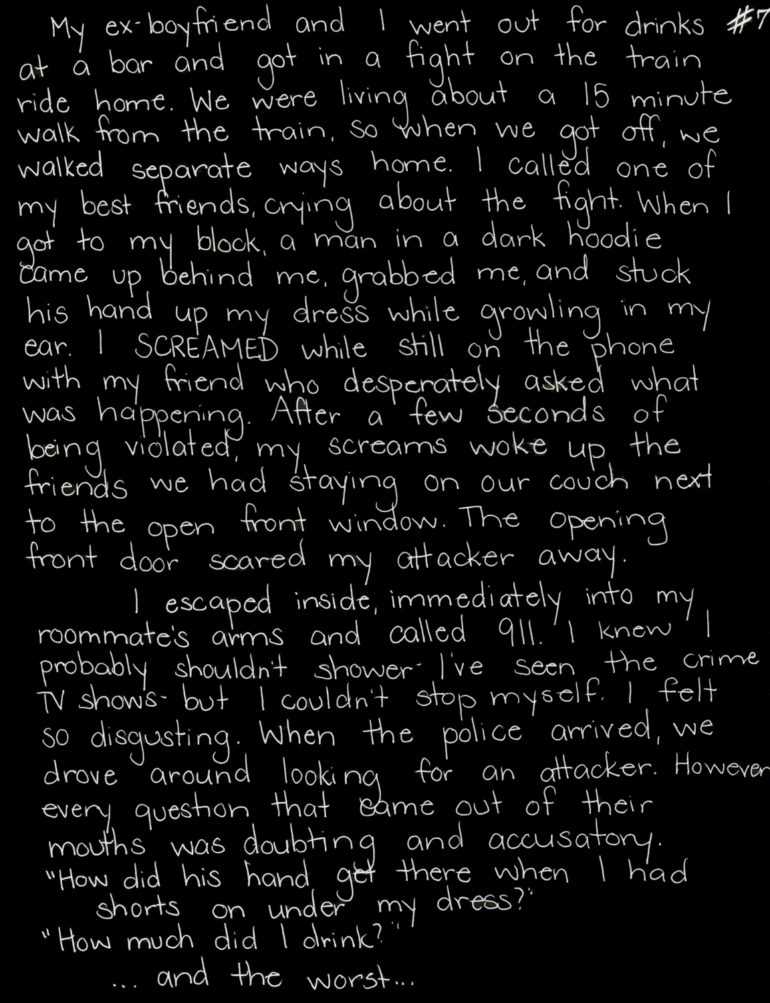

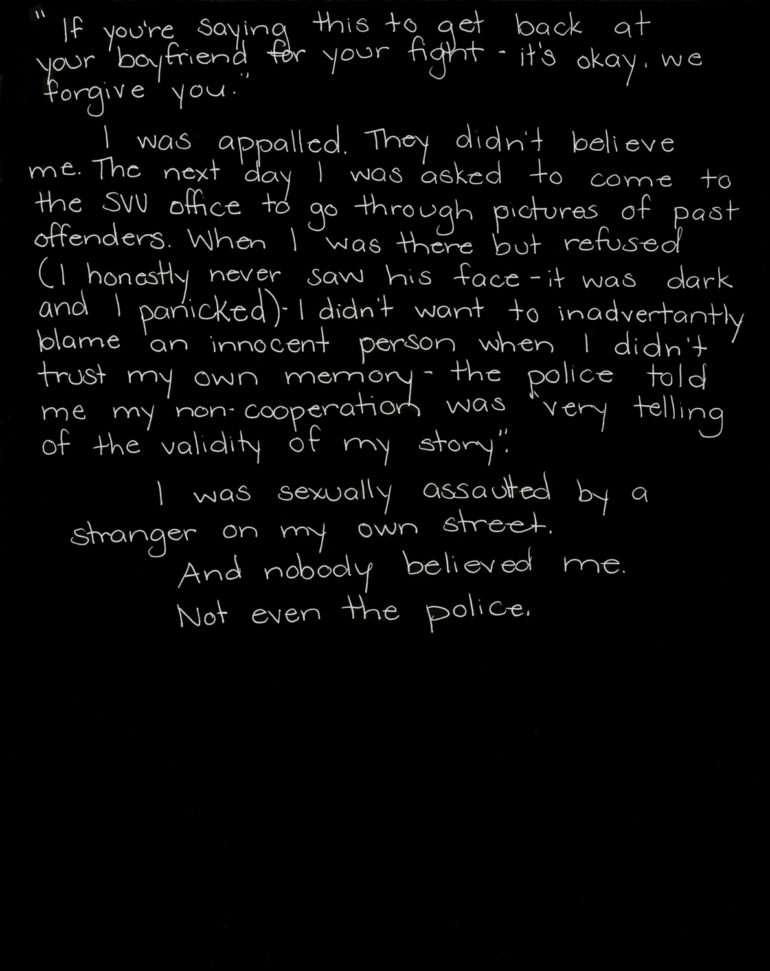

AM: Every kind of experience is represented by the women photographed for the project already. Two different participants have been victims of their fathers, and two cousins have been perpetrators – both of rape and sexual assault (groping). One woman experienced the standard ‘stranger-danger’ kind of attack on her walk home from the train (who manually violated and upskirted her). Several have been victims of their romantic partners, from threats of violence to rape. Mine was someone I thought was a friend, and was rape. With another participant, it was a childhood friend who always made her uncomfortable as they were growing up – she warned the family member he ultimately raped for years about the signs she saw (predominantly romantic advances she rejected), but didn’t know how to communicate the threat she kept picking up on. One woman’s attacker was her boss; another’s was her coworker. For a family member of mine, it was date-rape where she was targeted, intoxicated, and her two attackers took advantage of the situation together. One friends’ was a romantic interest who she told in advance that sex was not on the table (and he decided to take that from her anyway) before he even got there.

Every type and kind is represented, just due to the sheer numbers, and it will continue to grow as the pool of participants does as well.

Phoblographer: How do you hope to use the project? Is there a strategy in terms of using it to help drive change and awareness?

AM: The primary goal of this project is to provide its participants a way to come forward confidently and safely, and to break silences on an issue we as a society keep failing to take seriously (Brock Turner is still out of prison, Kavanaugh was still voted to the Supreme Court, and just a few days ago a bus driver who plead guilty to raping a 14 yr old student on his route was given no prison time – the judge’s reasoning was cited as because he had no prior arrests and only raped one victim. As if the number of victims somehow lessens the crime – would a judge rule the same way for someone murdering ‘only one’ person?

Without fail, the majority of our country responds to trying to bring attention to this issue dismissively, discrediting and disbelieving the women who are brave enough to come forward, attacking their character and blaming them for their own attacks.

This project protects the participants from that risk while still allowing them to speak loud and proud, and that’s always been the motivating, driving force behind it.

You can keep up with the project and follow the rest of Alyssa’s work by visiting her website.