All images by John Dykstra. Used with permission.

“When I finally picked up photography, I knew well my intentions to be an artist, and that if I were to ever get into photography, I would never be doing commercial or documentary work: the aim was to develop the craft into my own artistic ambitions.” says photographer John Dykstra about his photography. “What I didn’t know was how quickly my love for photography would develop.” Earlier on this year, I found John’s work on Reddit and talked to him about the series that you see here. It isn’t complete, but he’s been working on it and it’s developed into one that touches on how people see the world around them.

John started out in the creative world drawing and then got into photography. And as he explains, it’s not a simple art form to master.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

John: From a young age I wanted to be an artist, and it was during the process of exploring different media that I sparked a passion for photography. I was in high school when I received my first camera as a birthday gift from my father. I had expressed an interest to him and found that, once I had begun practicing the craft, I could not set it down. Before I got into photography, I had taught myself how to draw proficiently having invested several hundred hours into practice, and even took a few painting classes. By the time I was out of high school I was doing drawing commissions for a local company that needed product concepts imagined and rendered realistically. For my 16th birthday, my father purchased me a membership to the Detroit Institute of Art on my behalf.

When I finally picked up photography, I knew well my intentions to be an artist, and that if I were to ever get into photography, I would never be doing commercial or documentary work: the aim was to develop the craft into my own artistic ambitions. What I didn’t know was how quickly my love for photography would develop.

You see, at that point, I had reached a level of technical proficiency in rendering images with a pencil where I could create appealing images, but I had no vision. I was what I would call a talented craftsman, but definitely not an artist. In fact, I did not really have a working understanding of ‘art’ or what the artist’s role in society was, all I knew was that I could draw anything, and I was growing bored of that. At the same time, when I picked up a camera, it rendered everything immediately. I think it was mainly this attribute – the ability to render quickly – that appealed to me the most when I first began, because I could focus on other areas of experimentation with much more efficiency.

I learned a huge deal about composition with the camera just because of the ability to quickly compose and review fully rendered images and compose again. On the same note, however, what kept me hooked was the challenges that are innate with the photographic craft. With drawing, I could draw anything anywhere on the canvas. After many years of practice as well as study with photography, I knew that any conceivable image that I could come up with in my mind was perfectly capable of reproducing in a photograph, but it took a lot more thinking on how to make it happen since you’re using light – something you can see, control to an extent, but not touch – instead of paint, a medium far easier to get what you want out of it.

Photography may be the easiest craft to master, but it is the hardest art form to master, because of the inherent challenge of separating one’s work and imagery from completely representational of the real world, and learning to express oneself through control of the medium.

Phoblographer: What made you want to get into surreal fine art portraiture?

John: I fell in love with fine art portraiture when I took a few classes in college on studio lighting. For the longest time I thought I would be creating only landscapes, eventually moving into Andy Goldsworthy type of work. Then I took one studio class and it was all over – I loved shooting portraits! That’s not to say I won’t shoot landscapes or still lives again, but the process of shooting people totally transformed my work.

As far as surrealism, I think that’s a really loose term. I did have a period last year where I shot emulative work much in the line with all the typical dreamy portraits of people floating in the air of abandoned houses or floating in the water in some tranquil landscape, but that was really just trying to figure out what my style was. It wasn’t until I sat down to ask myself what it means to be an artist, and what an artistic vision is, that I started creating work that actually meant something to me and expressed some truth about the way I see my world.

“Photography may be the easiest craft to master, but it is the hardest art form to master, because of the inherent challenge of separating one’s work and imagery from completely representational of the real world, and learning to express oneself through control of the medium.”

Phoblographer: A lot of your work is about the balance between black and white with the exception of your color stuff; how does this help you to express yourself creatively?

John: I never saw it as a balance of black and white, but that’s an interesting observation. I’m very comfortable with black and white photography, and I find it very beautiful. Some of my favorite artists create their work in black and white – Michael Kenna and Noell Oszvald – and it’s something that more or less resonates better with me.

Phoblographer: When you go about creating these images, is there storyboarding happening? How do you communicate the ideas to your models?

John: My older work, the ‘Dream State’ series, there was some storyboarding involving a loose narrative about the protagonist waking up within an alternate reality. I would write out some scenes that illustrated a linear timeline, and shot it in that order. I figured out during this project that this process is totally not my style. I much prefer that each piece works on its own, each expressing something different.

Phoblographer: Where do you typically draw your inspiration from? A lot of it looks very American Horror Story influenced?

John: I have not actually seen American Horror Story! I don’t watch a lot of films or television. The inspiration comes from all around, however; philosophy, theology, artwork, music, literature, etc. I do a lot of thinking, and over the past year that thinking has been focused on developing a creative vision. Figuring out my world view, continually learning about life, and expanding my awareness has been fundamental for my work, and learning to disseminate what I know, believe in, or recently learned into my artwork challenges and motivates me to keep creating.

As far as my visual style? I think I’ve always been a little bit comfortable with darker feeling imagery, and I may need to bring in a bit of optimism to weigh it out.

“I think photographers need to know that they can create any image they can imagine from directly within the camera, it just takes much more forethought and ingenuity to make happen.”

Phoblographer: How do you want your photography and creativity to evolve and how do you plan on making that happen?

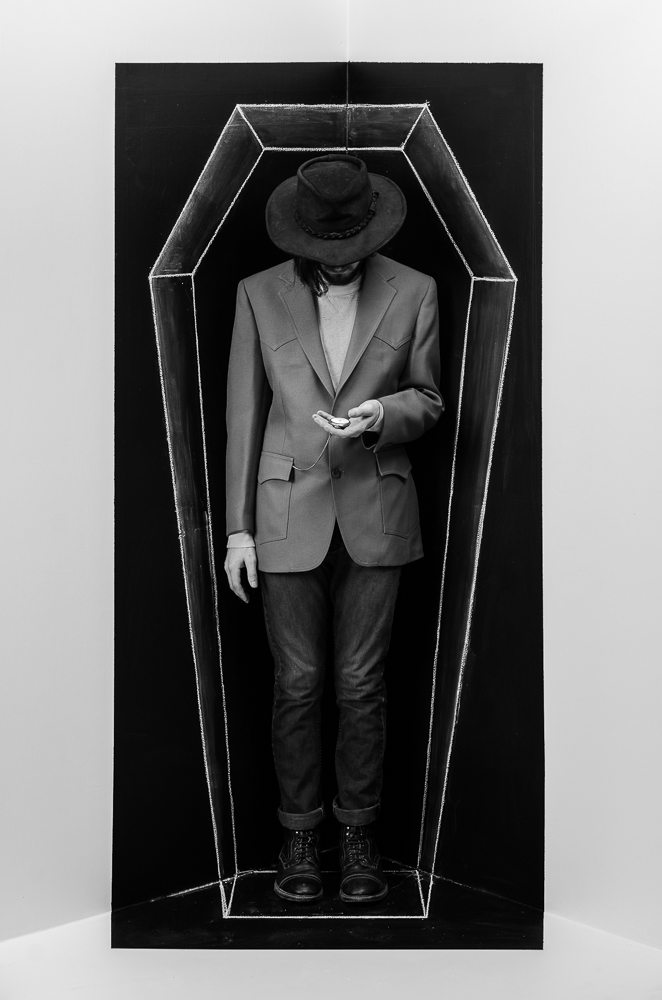

John: I want to continue working with perspective illusions while simultaneously using less and less post-processing work. I have absolutely nothing against post-processing, I’m all about it, but right now my work is playing the devil’s advocate against two schools of thought. First, I think most of the popular surrealistic photography spread across the Internet is very shallow, and Photoshop composites of floating people are becoming nauseatingly boring. Some of the best advice I had from an instructor was that if I was going to shoot surrealistic photography, make sure that it still remains believable. It’s a sort of post-modern approach: finding the unreal within reality.

I think photographers need to know that they can create any image they can imagine from directly within the camera, it just takes much more forethought and ingenuity to make happen. Second, I also dislike purists’ attitudes that there should be no post-processing. It irks me when people assume that the photograph is a carbon copy of reality. The very lens you put in front of a camera can warp the light coming in and shift the way the visual world around in a way that we could never see with our eyes. My perspective illusions are sort of my way of saying that not everything you see is as it at first seems to be.

Ultimately, however, I want to go to greater depths in expressing my ideals and outlook on the world. The main intent of my newest project is to simply show the importance of perspective, not just visual or artistic perspective, but mental perspective. The self-portrait I shot where I’m ‘boxing’ myself in, if you were to take a step to the side or move the camera, that box would break – it’s just an illusion – and that’s my way of saying that many of our boundaries in life are not only self-imposed, but imaginary, and that it just takes a bit of difference in perspective to set yourself free. It’s ideas like this that I want to explore. In the end, I want to both broaden and deepen my world view, and gain more perspective on life, and that’s where I want my work to head as well.