Last Updated on 03/23/2016 by Chris Gampat

All images by Ed Hanley. Used with permission.

Ed Hanley is a Toronto-based multi-dimensional artist–of which includes his affinity for photography. In fact, he loves doing documentary work.

On a visit to India, he ran across a Leprosy Ward. Leprosy is a very ancient disease that dates back to before the days of Jesus. folks with Leprosy would be forced out of town and into a cave so that their diseases didn’t spread.

But how do you go about approaching a project with such a touchy subject? We talked to Ed to see how he did it.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography.

Ed: I took a few photography courses in my last year of high school in Toronto, Canada, and continued to engage in photography as a hobby until a few years ago, when I decided to take it more seriously and start to use it as a medium to tell stories. Late last year I took a short documentary photography course at Ryerson University in Toronto, and then set off for 2 months on my 10th trip to India to tell stories with my camera. I should mention that I’m a professional musician, and play tabla, the principal percussion instrument of north Indian classical music, so I’ve spent a lot of time in India over the past 25 years and am very comfortable living and working there.

Phoblographer: What made you want to get into documentary photography?

Ed: I’m interested in telling stories, particularly to give voice to people on the fringes of society…photographing people affected by the 1984 Union Carbide Gas Tragedy in Bhopal, India is an ongoing project for example. I was particularly struck by the power of the photograph last year when Nilufer Demir’s devastating image of young Syrian refugee Alyan Kurdi on the beach in Turkey rocked the world, and, at home, actually changed the course of the Canadian federal election.

Phoblographer: So what made you want to photograph the residents at the Leprosy ward?

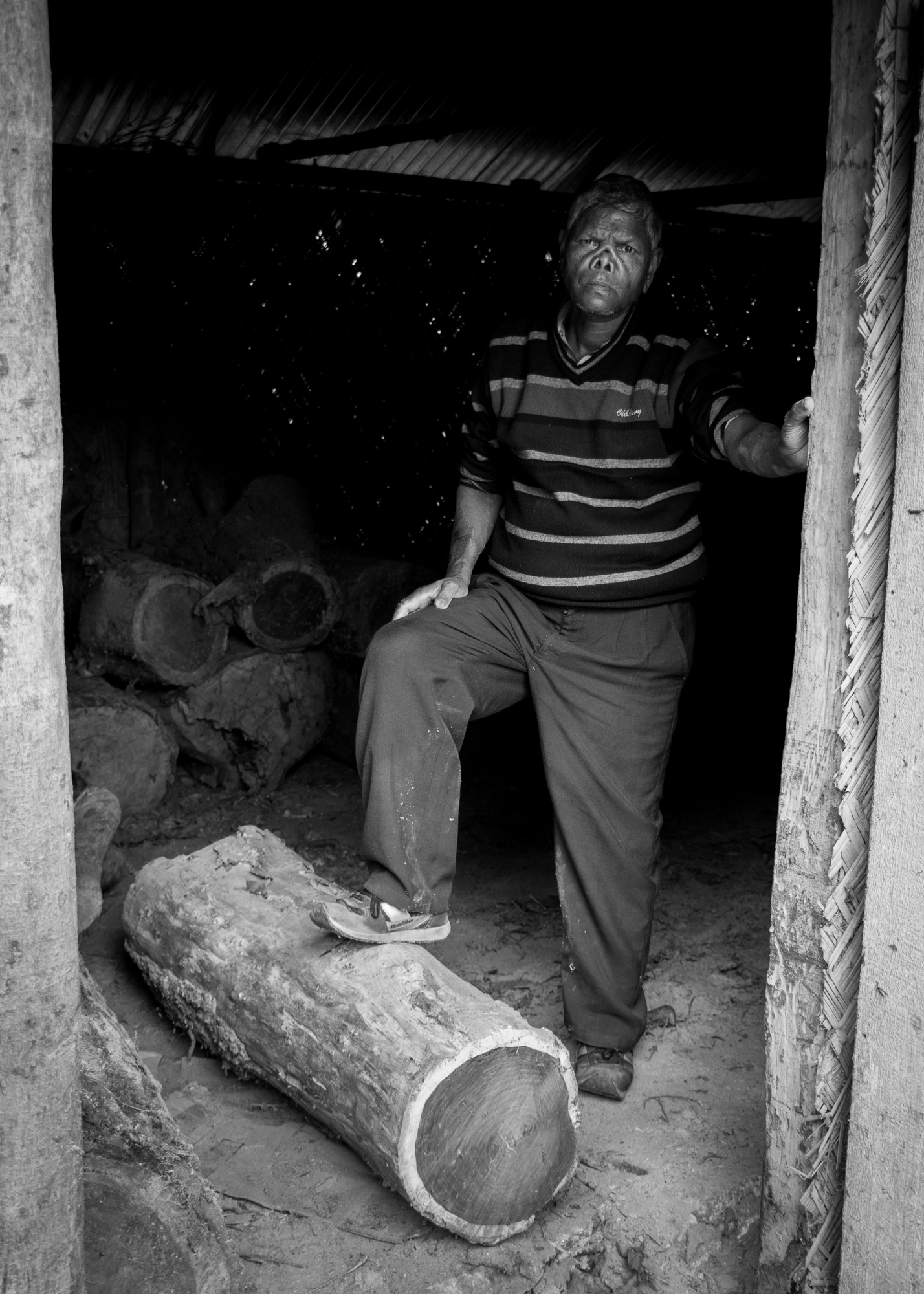

Ed: My first visit to a leprosy ward was unintentional. I was performing with students of a music and dance school in Siliguri, West Bengal when one of the teachers suggested a visit to the hospital next door. Part way through the tour of the grounds, we began to encounter leprosy patients, and the hospital director began sharing their stories. The stories were heartbreaking…myths and misconceptions around leprosy result in sufferers being rejected by their families and cast out of their communities, unable to find work or accommodation, ostracized and stigmatized in every possible way. We continued to the leprosy ward itself and I began photographing the patients and writing down their stories. I made a second visit a few days later with an audio recorder and my portrait lens for more detailed work. I knew nothing about leprosy at the outset, and the more I learned, the more it became clear that these voices needed to be heard.

I self-published a photoessay on Atavist, which found its way to the World Health Organization head office in Geneva, then to the head office of the WHO’s Global Leprosy Programme in Delhi. Through those connections I was introduced to the director of a leprosy hospital in Sanawad, MP, about 5 hours by car from where I was working in Bhopal, and I travelled there to make another set of photographs and record another set of stories. This led to an invitation to the WHO leprosy office in Delhi, where I worked with chief medical officer Dr Laura Gillini, visiting two leprosy colonies to capture images, video and stories to illustrate and promote the WHO’s 2016-2020 Global Leprosy Strategy.

Phoblographer: How did you go about approaching this project? Of course, you needed permission but what about planning and gaining the trust of the people?

Ed: Initially there was no plan, and the first visit was very much improvised…I captured anything that might be pertinent… the hands, feet and faces of the patients; ulcers and bandages; the staff, equipment, grounds and the hospital kitchen, everything. On subsequent visits I narrowed the view a bit and looked for images that would tell the story of the social impact of leprosy, as well as the hope of rehabilitation. Due to the stigma, it was very important to ask each patient for permission to capture and publish their photographs. No one declined, and many were eager for an opportunity to tell their stories. I had a guide in each location, either the hospital directors or patients themselves, who acted as translators when necessary.

The simple act of listening is remarkably powerful, and I always listened first, then asked if I could take photographs. I think if people know their story will be told in their own words, they are more comfortable when the camera comes out.

Phoblographer: What health precautions did you take when doing this project?

Ed: Nothing special, other than hand sanitizer before entering and leaving, as you would at any hospital. Leprosy is not highly contagious, completely curable, and patients are no longer infectious after 2 weeks of treatment, so it’s not a dangerous environment by any means.

Phoblographer: When you went into the project, did you have a full creative vision involving what you wanted? Do you feel like you got what you wanted or the project evolved into something else?

Ed: I didn’t have a vision initially…I’d only ever made 2 photo essays before, so once I had the first set of images I started to find my way through edits, research and writing. It was clear that stigma was the focus, but I realized that some background info on the disease was necessary, so I learned as much about it as I could, and started to try to find a flow. Editing down to a final set of images is always challenging…it was important to show that leprosy affects men and women of all ages, the debilitating physical effects, but also somehow the social effects of stigma, which are not easy to capture in a static image. Once a draft was in place, I reached out to some friends… a journalist suggested a text edit, a photojournalist suggested a stronger title image, and my university professor made suggestions that tweaked the emotional rhythm… all of which improved the piece.

Phoblographer: Whose story did you feel stood out at you the most? Why?

Ed: “I was beautiful before, but now society has rejected me” Rekha, age 30, at St Joseph’s Leprosy Centre in Sanawad, Madhya Pradesh.

Of all the stories, Rekha’s touched me the most. After leprosy caused her nasal cartilage to collapse -an uncommon but devastating facial disfigurement- her husband left with their three children. She now lives with her mother, can’t find work, can’t attend community events like weddings or celebrations, and people laugh and shout at her in the streets, so she stays inside most of the time. I triple checked that she was ok having her photo taken. She said “please show people my photo so they will understand”. She heard a photographer was coming to the centre, and was waiting in the lobby, with her portrait, when I arrived. After she told her story, we started the shoot, but her instinct was to turn away from the camera and hide her face, and it took incredible strength and bravery for her to overcome that…to look straight into the camera and have her photo taken. That is something I will never forget. It was very difficult to watch.

There is reconstructive surgery available for Rekha’s disfigurement, but the centre is struggling to raise the necessary funds.

Phoblographer: So what’s your intent with this project?

Ed: I’d like to try to raise awareness about leprosy, and particularly leprosy stigma. The Indian government declared leprosy ‘eliminated’ in the year 2005 (defined as less than 1 new case per 10,000 people) and as a result, much of the research and education money has dried up. India has remarkably robust and powerful public health campaigns against tobacco and alcohol use, so the know-how to launch a campaign aimed at educating people to reduce leprosy stigma is definitely there, it’s just a matter of resources and political will. Both governmental and non-governmental centres are constantly short of funds: one hospital I visited has a surgical suite on loan, ready to begin reconstructive hand surgeries, but no surgeon to carry out the procedures. I’d like to continue this work on future trips to India.