Last Updated on 05/25/2023 by StateofDigitalPublishing

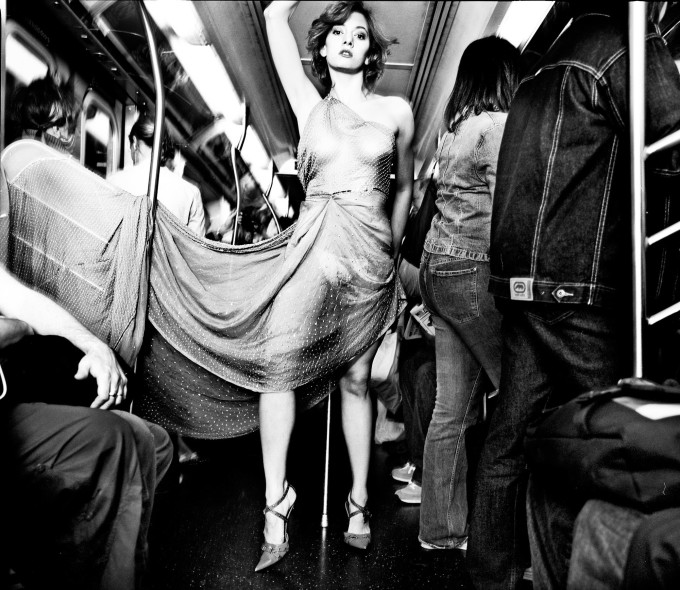

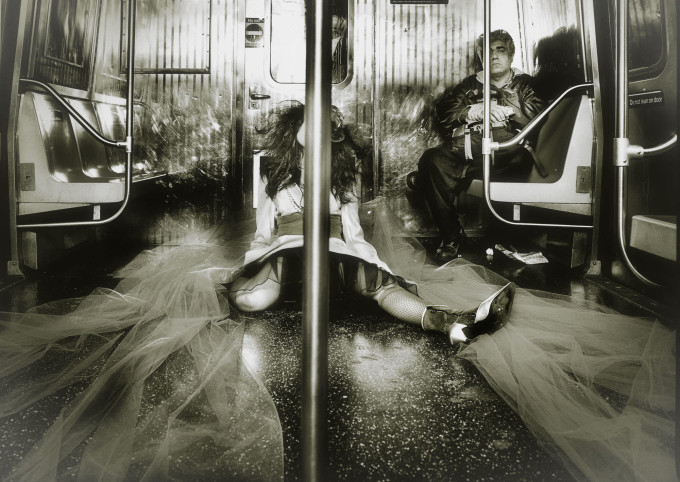

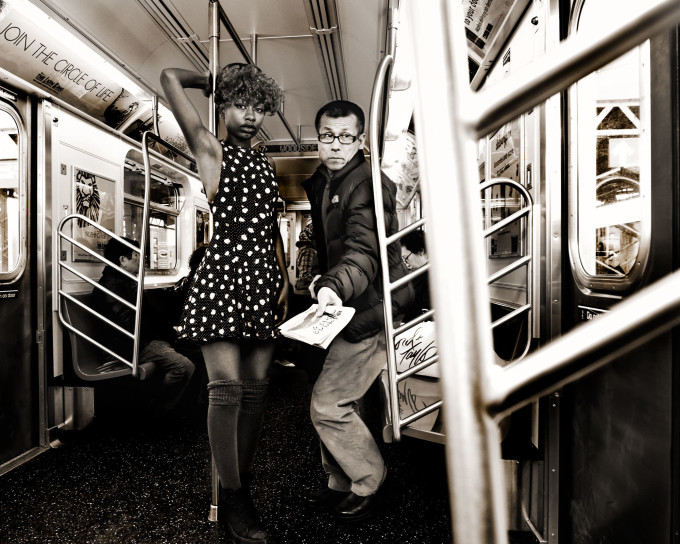

All images by C. Stephen Hurst. Used with permission.

“The real turning point though was when I was diagnosed with cancer.” says C. Stephen Hurst about how he got into photography. I accepted the possibility that the lymphoma would kill me but I couldn’t accept that my work as photographer, and not a painter, would end.” Indeed, when you’re on a deadline like this, you try to do as much as you can in the time that you have left.

C. Stephen Hurst is a photographer based in Brooklyn, NY and instructs at ICP. Luckily, he’s a cancer survivor and can go about creating some of the most inspiring work that I’ve seen so far this year. Part of this stems from the fact that he’s a former painter. While he shoots weddings, some of this work includes his fashion shoots on the NYC subways.

“Usually I’ll time the ride several times and then base my calculations of setting up, shooting, and breaking down on the average time between those stops.” says Stephen. “It evolved out of a desire to shoot during winter in a free ‘non studio’ space. NYC at any time has a wonderful abundance of models to collaborate with but none of them are as unique, unpredictable, or iconic as the streets/subways/random people (and animals) of our great Metropolis.”

This specific body of his work is about documenting worlds as they collide.

Phoblographer: Talk to us about how you got into photography?

Stephen: My father was an avid hobbyist portrait photographer and I inherited that love of the medium to document and create though in practice I started out as a self taught painter. German expressionism and Futurism were my idols but over time I felt the pull from that visual world to the immediacy and interactivity of Photography. The real turning point though was when I was diagnosed with cancer. I accepted the possibility that the lymphoma would kill me but I couldn’t accept that my work as photographer, and not a painter, would end. I guess you can say this is when I transitioned from being a hobbyist to being a more focused practitioner of the craft.

Phoblographer: What made you want to get into portraiture?

Stephen: The human face. It is more complex and striking than any landscape I have come across. I started out shooting street photography but became frustrated with how many ‘decisive moments’ I missed. I couldn’t go up to the stranger on the street and ask them for a redo. ‘Sir, could you walk around the corner just like you did fifteen seconds ago, chewing veraciously on that toothpick, but this time turn your face toward the refracted light beam coming from the building across the street. Let me shoot three to six frames of you as you catch me, disapprovingly, out of the corner of your eye.’

That didn’t, couldn’t, or wouldn’t happen so I began to yearn for a slower processes where I could direct and play on technical or aesthetic variations more freely.

Phoblographer: This project is pretty unique! Where did you draw the inspiration from and what influenced its creative direction?

Stephen: Overall, two photographers have been huge in my development as a photographer. Weege, and, Thierry le Goues. Wegee for his dedication and sacrifice to the craft. His portraits seem as if they were to explode off the printed page. And there was the discovery of Thierry’s with his 2nd book, Popular, which brought it together for me. I became very emotional perusing though that extended essay of Cuba. I was or rather, still am mystified by how the genres of Fine Art, Portraiture, Photo Journalism, and Travel Diary blended seamlessly into a body of work that is both fashionable, rugged, and yet timeless. For me, It was a revelation.

More specifically with this project I wanted to shoot in a space where New York itself has equal billing to the model and I wanted to do it cheaply. In addition I am heavily influenced by the Futurist painting movement (turn of the 20th Century). They advocated for an art that was intertwined with speed, conflict, and mechanics. I wanted to challenge myself to see if it were possible, to convert the main arteries of our subway system into an urban and mobile studio space that is part photo shoot and part performance piece with rider participation (or not).

Phoblographer: So talk about your specific creative vision? How did you go about getting folks to stay in place, the performers to be there and how did you just go about doing this project?

Stephen: I tried to prep as much as possible about model placement and interaction but not everything can be predicted. I wanted to have a sense of magic realism. Something that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Jorge Louis Borges short story. I had a general sense that the performers would be on that train at that time but my ability to communicate in Spanish is very limited. Luckily my Make Up artist was fluent and as they boarded our train we went straight into action. I essentially had 2:52 seconds to shoot so to grease the wheels and avoid the small talk I gave them twenty dollars. I set them up how I thought appropriate and told the model to be my mirror. Whatever motions I made she took and made a thousand times better. My assistant set up the kit and we already worked out the light intensity based upon a piece of 12 foot string: from assistant to model, distance of the strong, and at setting of 5.3 on the power pack we are at f/5.6. I asked my assistant to be aware if had to move closer or further away let me know I would so I could adjust the f-stop accordingly.

Phoblographer: Talk logistics to us. How did you avoid cops? Lots of this looks like direct flash, so was it just a flash in the hot shoe? Were you very specific about the times that you’d go onto the train?

Stephen: Ah logistics. For a shoot like this I scouted the train lines, measured times between stops, metered ambient light in various areas of the train (i.e. center w/ pole versus the far corners of the train line or door openings.). Subways ridership at certain times is also important in order to figure out how camera angles and light placement will be effected. Some train lines are quite loud so to maximize efficiency I rehearse with the model 15 to 30 min prior to being on the subway. In this limited time I try to develop a sort of shorthand sign language so we (me and model) can be as efficient as possible moving through the train car. In addition I calculated estimates of how long after the doors close would it take for me communicate to the people on the train what we are about to do, place the model, setup, shoot, and then pack it up and keep moving. To avoid conflict from either police or riders I prefer to shoot between two stops maximum and then get off or transfer to another line. Similar to shooting Fashion on the streets I fear being stationary for too long.

Lighting is simple but cumbersome. An old Hensel Porty with a beauty Dish that has a center grid so the middle is hotter than the otter rim. This is hand held by an assistant approximently 12 feet in front of model with me moving in between the two.

Phoblographer: So when you were in the editing process, what determined whether an image made it into the series or not?

Stephen: How ’emotionally raw’ it felt for lack of a better term. Editing is a mysterious process. One can rely on the technical as to what makes a good photo or not but at some point I need to emotionally connect to a particular image over the next.

Phoblographer: Why the choice of just black and white?

Stephen: It just spoke to me in B&W and Sepia. The models and the process of shooting in the train system is an abstraction to the everyday commute. B&W is an abstraction to the way we normally see the world. In addition, the colors and the clothes of all involved can, over time, feel dated and incongruent. B&W helps to neutralize this sentiment.