Three years ago, I walked into the International Center of Photography for the first time before I was due to meet a friend. It was a chilly February afternoon in 2010 as I was working my way down from Central Park, where I had been taking some photos. I hadn’t heard of ICP before, but given my family roots in photography (you can see a truncated version of that in my staff bio), I felt compelled to enter. The major exhibition on the main floor was that of Miroslav Tichý, a reclusive Czech photographer who, among other things I learned, made his own cameras, cut his own glass, and paid no mind to the quality of his images. There’s more to be told, and I will tell it to you as it shook the foundation of my then-nascent practice and understanding of photography.

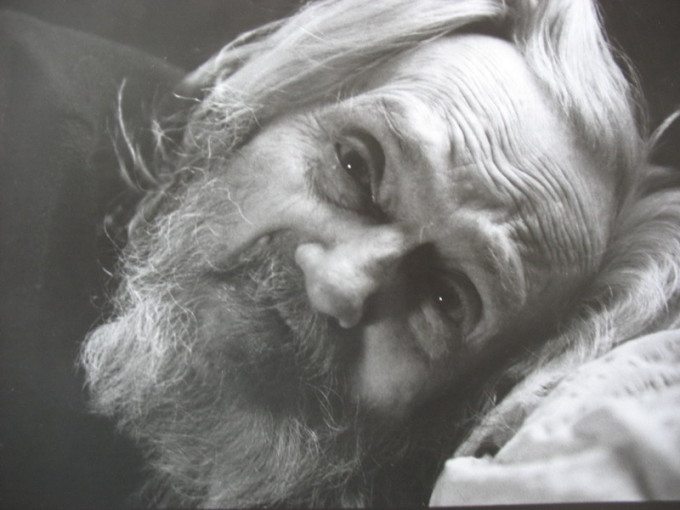

My memory of the sequence in which I viewed the photos and the precise layout of the exhibit is somewhat hazy now, much in the same way a Tichý photography is hazy. At first glance, his photographs are a curious thing. The tones are muted. The subjects (oftentimes women) are out of focus. The photographs themselves are worn out, and age is not the only reason. As I moved along the wall, a semblance of an understanding of his work began to take shape.

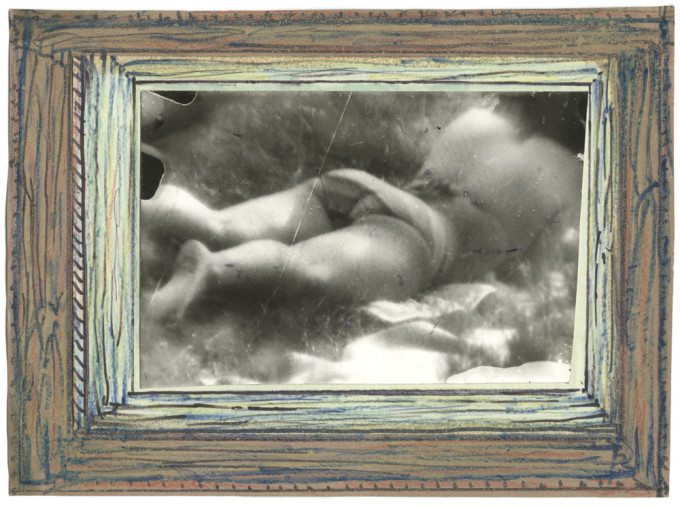

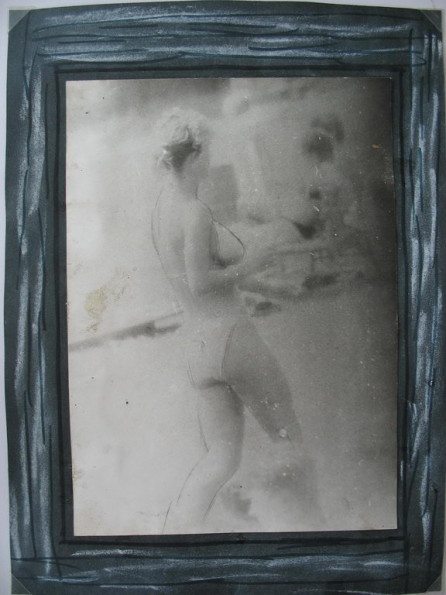

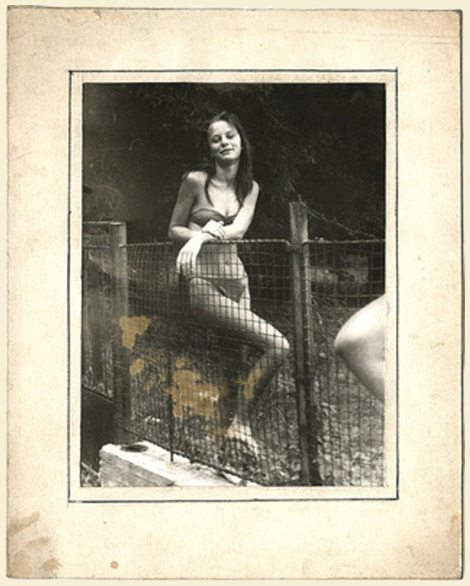

There were bits of text sprinkled throughout the exhibit that shed some light on who he was, where he lived, his history, and his work. He lived in a small town called Kyjov in what is now the Czech Republic. Most of his photographs featured in the exhibit, and most of his photographs in his entire oeuvre, are of women. Tichý would amble down to the local pool and take photos with his homemade cameras of the women there. Some of the women are blurred to the point where they’re nearly formless, in that they have no apparent identity.

At the back of the exhibit sat some of his cameras and negatives in a glass case. My understanding of what a camera was or could be quickly dissolved. These creations of artistic genius with a dollop of insanity begged the question, “What is a camera?” Tichy’s machines were made of cardboard, tape, wires, glue, spools, and other raw materials. The lenses, too, were all his own. There was no autofocus, no live view, no auto white balance, and the list goes on. I’m not even sure if the cameras had viewfinders, not that I can remember at least. Tichý designed his cameras to be functional at the most basic level. Expose the film to light, and develop the image at home.

At the height of his photography, he would shoot as many as ten rolls a day. With that many images, one might think that there would be at least one clean photograph, but Tichý encouraged the destruction of his work by stepping on it, mishandling it, leaving it on the floor, and the like. The physical condition of the image became a part of the image itself. There’s an air of carelessness about his images, but he would contrast the decay with handmade frames. Perhaps this was a way to honor the passing of time as the images became worse as time wore one. In some instances, Tichý would pencil an outline where time and decay took its toll.

There was a film, Tarzan Retired, playing on loop at the exhibition that showed Tichý in his home studio and elsewhere, and the filmmaker also managed to find some of the women Tichý photographed decades ago. Born in 1926, Tichý originally trained to be a painter, and came to photography later in the 1950s. Photography became his main mode of expression, the one for which he will be most remembered. Tichý said, “…the mistake is a part of it, it is poetry…and for that you need a bad camera.”

Tichý died on April 12, 2011, a little over a year after I saw his work at ICP. During Christmas Eve 2010, I showed my grandfather a NYTimes article about the exhibit as I thought he’d be interested. He ran a photo lab for several decades (that’s a story for a different post). When he saw the name “Tichý”, he paused for a moment and said that Tichý was his mother’s maiden name. My mind went into overdrive as I tried to gauge the possibility of my relation to him. It’s still largely unknown whether or not we’re distantly connected. I’d like to think that we are, but it will take a substantial amount of time and far more information than I have now to say anything with certainty. For now, I’m content with the idea that we might be.

Tichý’s photography is anything but conventional. He paid no mind to what it was he was shooting with, at least it seemed that way. Tichý could have easily bought a camera, but he created one (several, really) from the materials at his disposal, which suggests that he cares more than most. There’s a certain aesthetic he achieves that only his home-brew cameras made possible. He liked pretty women, and he liked to take pictures of pretty women. His photographs are erotic, but not in an overt way. You could say they’re simply the record, the photographic ramblings of an old codger, of the women in his home town of Kyjov. He was regarded with a certain degree of apprehension. An unkempt old man with a junky looking camera hanging near the pool? Surely that must have raised a few eyebrows, but most probably thought the cameras didn’t work. What they thought was largely a nonissue as he took the photos anyway. His mantra was simple. “Just put on the lens, and go.”

Sources: NYTimes article, ICP, Tichy Ocean, tichyfotograf.cz

Please Support The Phoblographer

We love to bring you guys the latest and greatest news and gear related stuff. However, we can’t keep doing that unless we have your continued support. If you would like to purchase any of the items mentioned, please do so by clicking our links first and then purchasing the items as we then get a small portion of the sale to help run the website.