Last Updated on 12/19/2017 by Chris Gampat

All images by Eliot Dudik. Used with permission.

Eliot Dudik is a recipient of the PDN 30 New and Emerging Photographers to Watch award. He received the highly coveted award for a photography project he did called, “The Road Ends in Water” that documented the lifestyle and culture of people who live by the water in the United States. But like any artist, he isn’t stopping there. Eliot is beginning a new project centered around the Civil War and how some of its influence still lingers around the south.

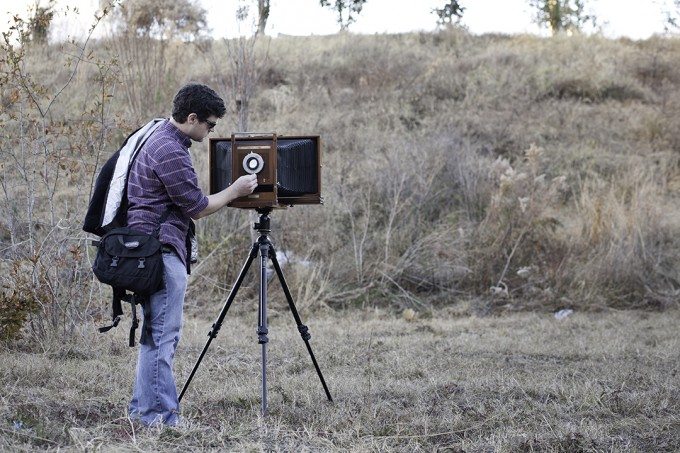

To accomplish the project, Eliot has been researching what to use to document his findings and eventually settled on an 8×20 camera; and he’s loading it up with two sheets of Kodak Portra 8×10 for each exposure. I recently had the chance to chat with Eliot despite his busy schedule. Here’s what he had to tell us about the camera, the project, and the documentary process.

Phoblographer: The Road Ends in Water was a project about the lifestyle of people who lived around the water. What is the title of your new project and what will it be about?

Eliot: I do not have a title for this project as I’ve just begun shooting it. I don’t tend to settle on a title until a project is near finished because my direction tends to shift one way or another as the work unfolds. This is one of my favorite things about photography: initial thoughts are often altered and rearranged as one investigates deeper. In a broad sense, the photographs will explore the Civil War and how it continues to exist today. I have been struck by the constant consciousness of the war that hangs in the air here, and intend to explore that presence through story telling and photography. I am interested in exploring the landscape that seems to continually breathe the spirit of the war. I am interested in the people who fight and die, over and over again, on battlefields and surrogate battlefields in an attempt to keep the history alive. I will be traveling to numerous reenactments to converse with and photograph the folks who perpetuate this cycle. As we are in the midst of the sesquicentennial, I am excited to begin; my first exposures have already been made.

Phoblographer: The project’s success got you listed in the PDN 30 Photographers to watch. Congratulations! What advice can you offer to other photographers looking to grow the way you have?

Eliot: You have to set goals, easy goals and tough goals, and you have to work hard to knock them off your list one at a time. I was recently watching a documentary and a photographer said, “to be a successful artist, you have to have passion and purpose,” which I think is as distilled as it gets, and likely true for many other fields. I think you must have both, and you must use both to drive toward your goals.

Phoblographer: Your approach to photography can probably be classified as fine art/documentary. How do you approach your subjects and get to know them. For example, my mentor never used to shoot a single photo for the first three days. Then he would get into it after getting the subjects comfortable with him.

Eliot: My approach to making portraits changes with each individual. Sometimes I spend less than an hour with someone before we decide to make a photograph. Other times I spend hours with them, whole days, or multiple outings. Sometimes I go exploring with them, and other times they come exploring with me. Regardless of the situation or individual, I always leave the camera in my vehicle initially. I want folks to see they can trust me first, only then can collaboration take place.

Phoblographer: You’ve shot large format before, and Road Ends in Water was done in 4 x 5. But your new project is being done is 8 x 20. Tell us about the camera, the lens, how you got it and why you’re choosing it.

Eliot: The 8×20 camera is known as a banquet camera, and the particular model I am using is a Korona Panoramic View made by the Gundlach-Manhattan Optical Co. in Rochester, NY between 1914 and 1930. The lens I am using right now is a C.P. Goerz Dagor 12 inch F/6.8. It is a little wide for my taste, so I am working to track down a Dagor 14 inch. The camera belongs to a friend and mentor of mine who is letting me borrow it. Right now, I only have one film holder for this camera, which grants me two exposures. In this way, I’m afraid I might feel a bit like a Civil War soldier who hopefully gets two shots off before he runs out of luck… As with another lens, I am in the process of tracking down some additional film holders. I have a great film changing tent, but these holders are just too gigantic to maneuver within the tent, so for now, I hope to make each shot count.

Phoblographer: Tell us about the film you’re using. Why did you choose it?

Eliot: When I first became interested in the 8×20 camera, there was still the Efke company, located in Croatia, making 8×20” black and white film, which, as far as I can tell, as now been discontinued. Regardless, it was black and white, and I really wanted to keep working with my beloved Kodak Porta film. I have been using Portra for years, it is what I have come to know and love. Of course I can trust it will produce fabulous skin tones, but I also love the subtle ways it renders a landscape.

“You have to set goals, easy goals and tough goals, and you have to work hard to knock them off your list one at a time.“

I decided I would attempt to slide two sheets of 8×10” film into the holder, making one exposure on two sheets at the same time. The film would then be drum scanned separately, and stitched back together, leaving the film edges and a narrow space between the two sheets of film creating something like a diptych. I think this is visually more interesting than a solid sheet of 8×20, but granted, much more difficult. I have been practicing with some black and white film in anticipation to begin shooting the Kodak Porta. I built a jig to slide the two sheets into in the dark, and tape them together. That process is going well, although I hope to refine it over time, and hopefully remove from the process the blind scissor cutting of excess tape as soon as possible.

Phoblographer: When you go onto doing projects like this for a prolonged period of time, how do you plan logistically? I mean you need funding, you need food, shelter, and you overall just need to plan. What are some tips that you can provide for aspiring artists?

Eliot: I spend a lot of time pacing around, going over things in my head. It is kind of like a nervous twitch, except I cover a lot of ground. I attempt to hash out every possible scenario and discover the positive and negative potential for every situation. I know it sounds dreadful, but it’s somewhat like a choose-your-own-adventure; it can be quite exhilarating. It’s how I go about planning for most things in life. I’m not sure I would call it a tip, especially since it tends to annoy everyone around me, but it is one way I go about making plans. It’s impossible to plan for everything, so you have to be flexible, but I often find when I do hit a speed bump, I have already thought about possible adjustments.

As for planning for specific things like funding, food, and shelter, let’s face it, it’s all about funding, and we could all use more of it. It takes funding of one kind or another to do extended, long distance projects, which is one reason being selected for a Guggenheim grant is on my list of long term “tough” goals. In the meantime, while we are all working toward our Guggenheims, don’t be afraid to look to your friends for help. Help doesn’t have to come in a monetary form. Friends can offer a place to sleep when working out of town, they can offer contacts, ideas, and inspiration.