Last Updated on 07/22/2023 by Lara Carretero

“I believe that the human matters much more than the gear,” expresses Nicholas Freeman, a self-described in-camera artist based in Los Angeles. “That a creative person could use any gear to achieve great results.” I first came across Nicholas’ work by pure chance, just by scrolling through Twitter as one does on those hot, sultry summer days when your energy to do something other than holding your phone is just unavailable. I stopped scrolling immediately, mesmerized by the complex interplay between lights and shadows, visibility and invisibility, darkness and its opposite. When upon further looking, I learned that he did most of his work in camera? I had to ask for this interview. And I was lucky enough to get answers.

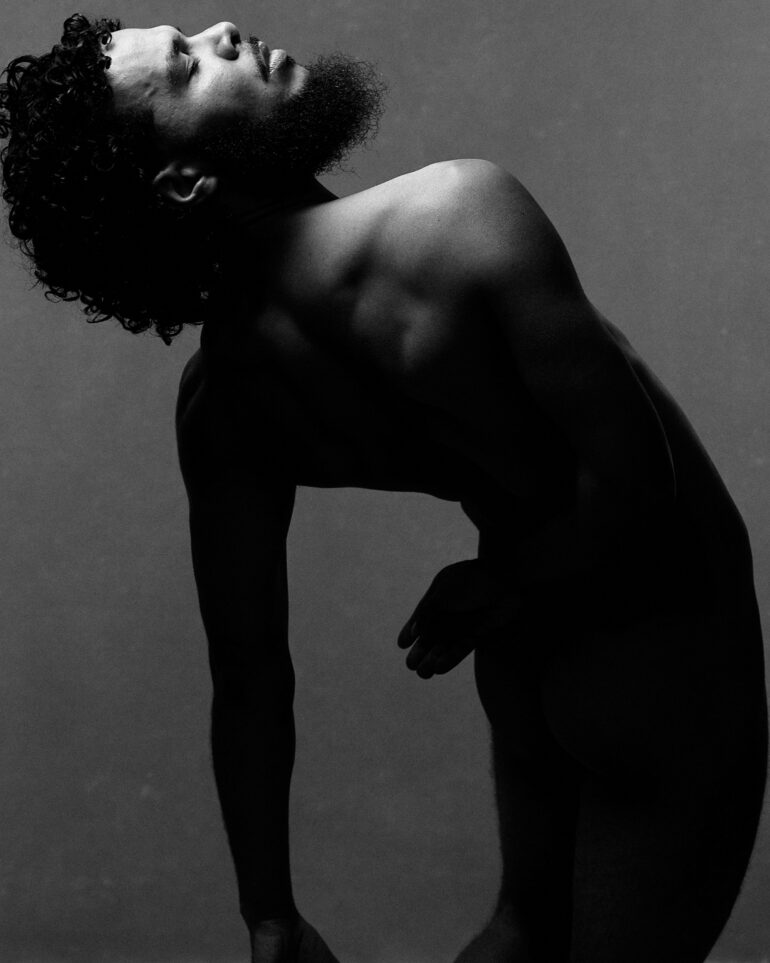

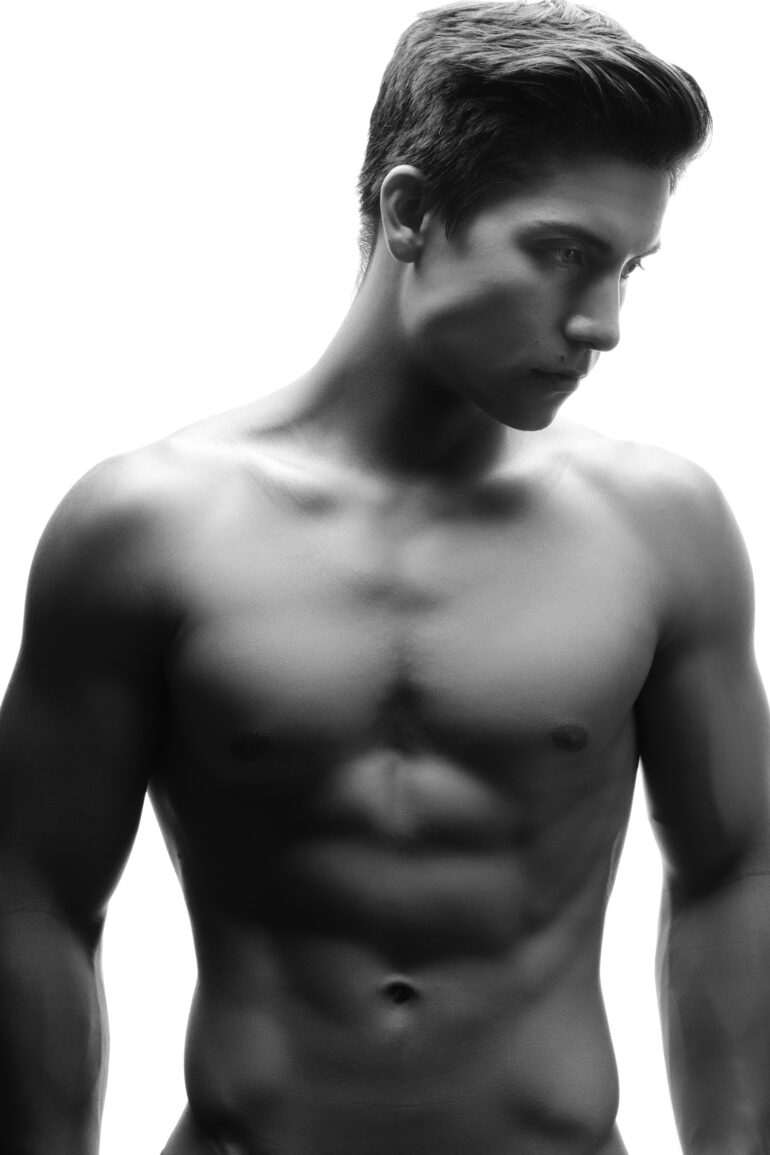

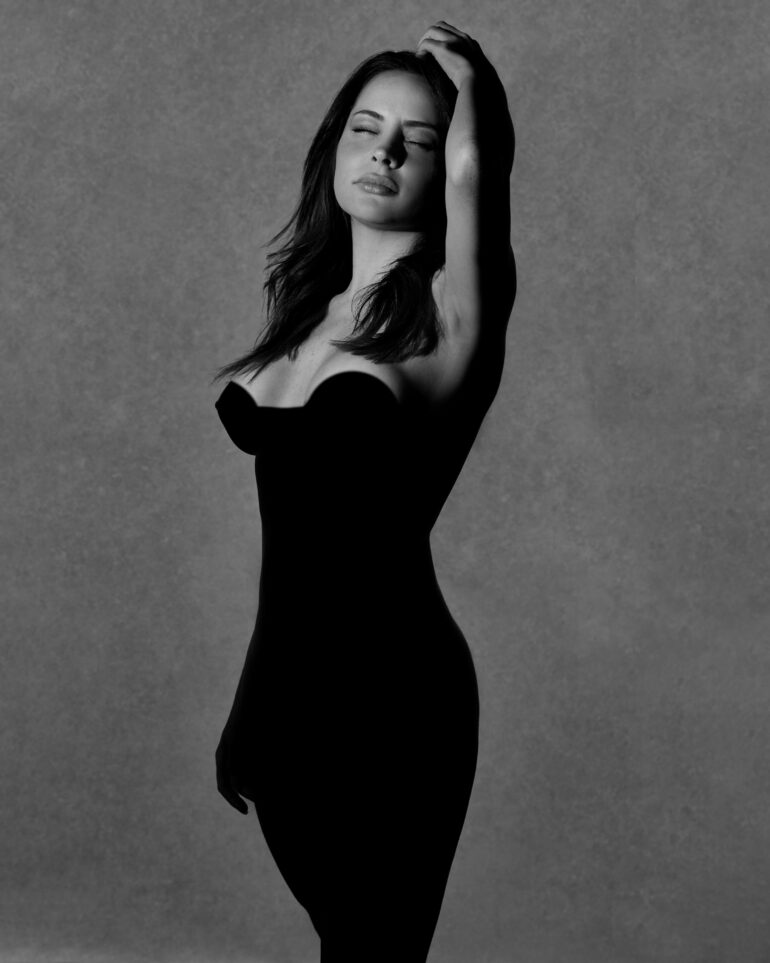

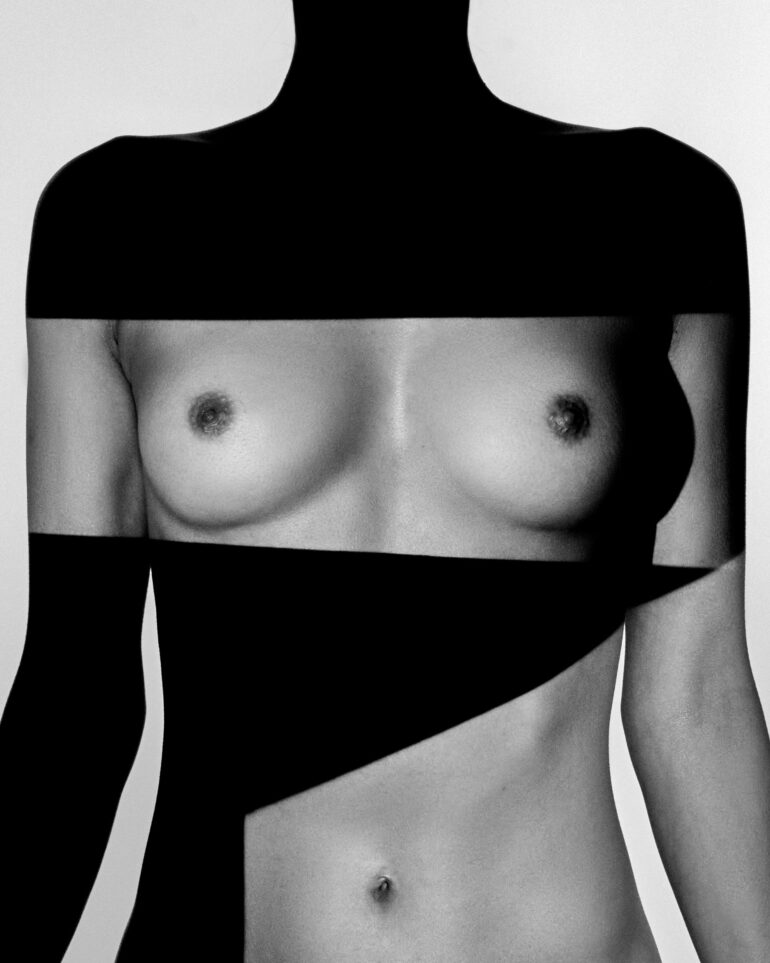

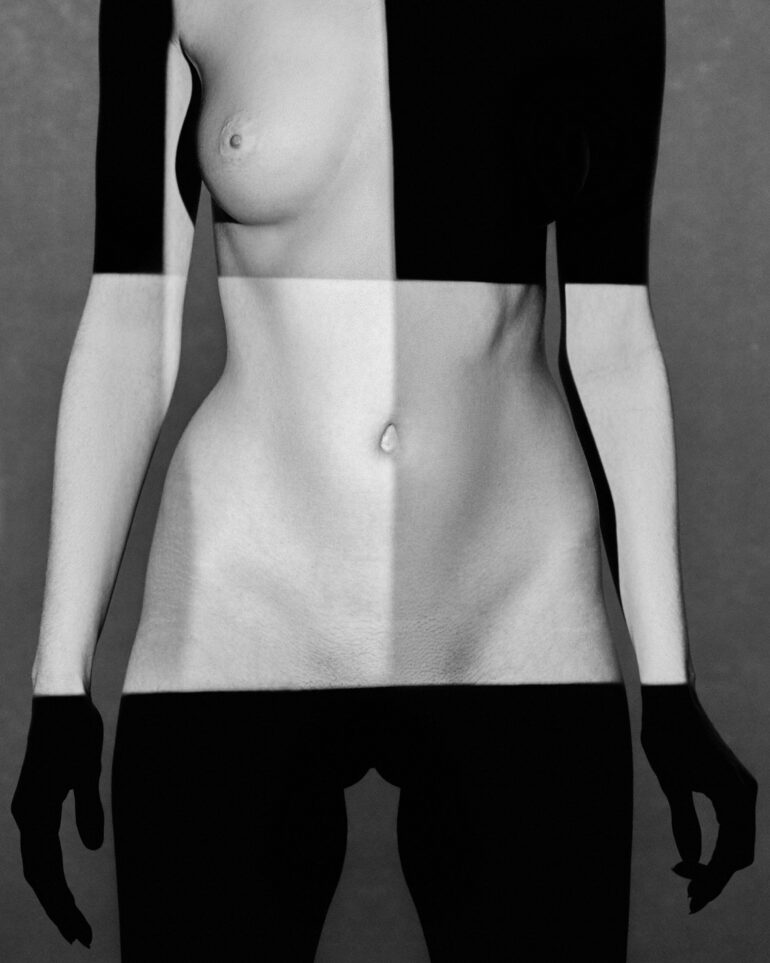

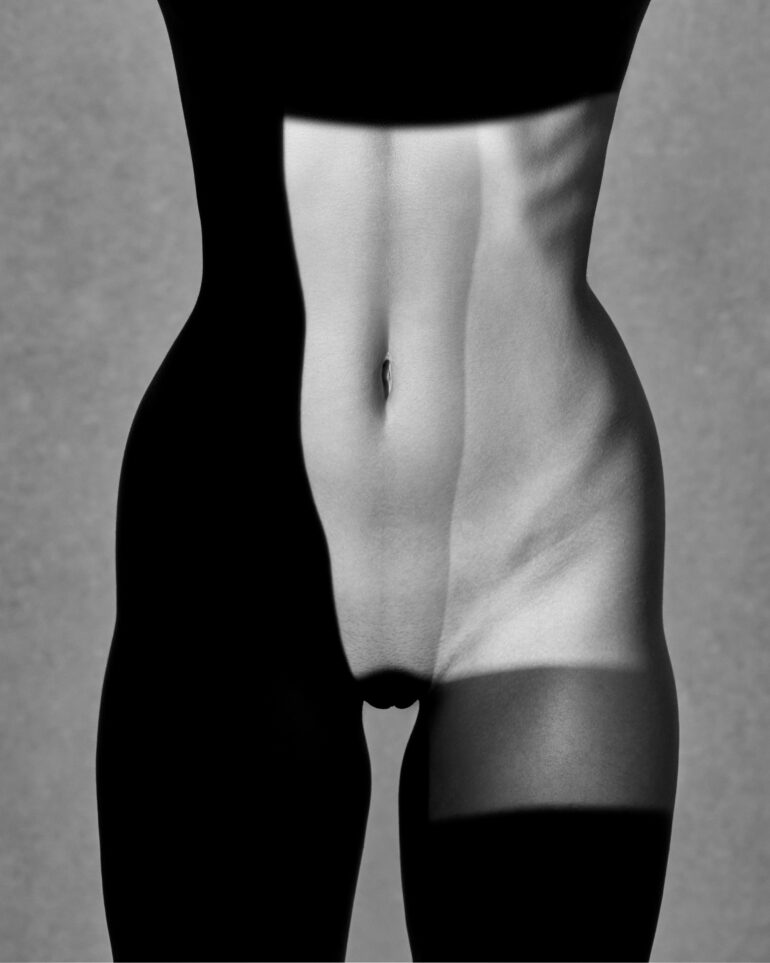

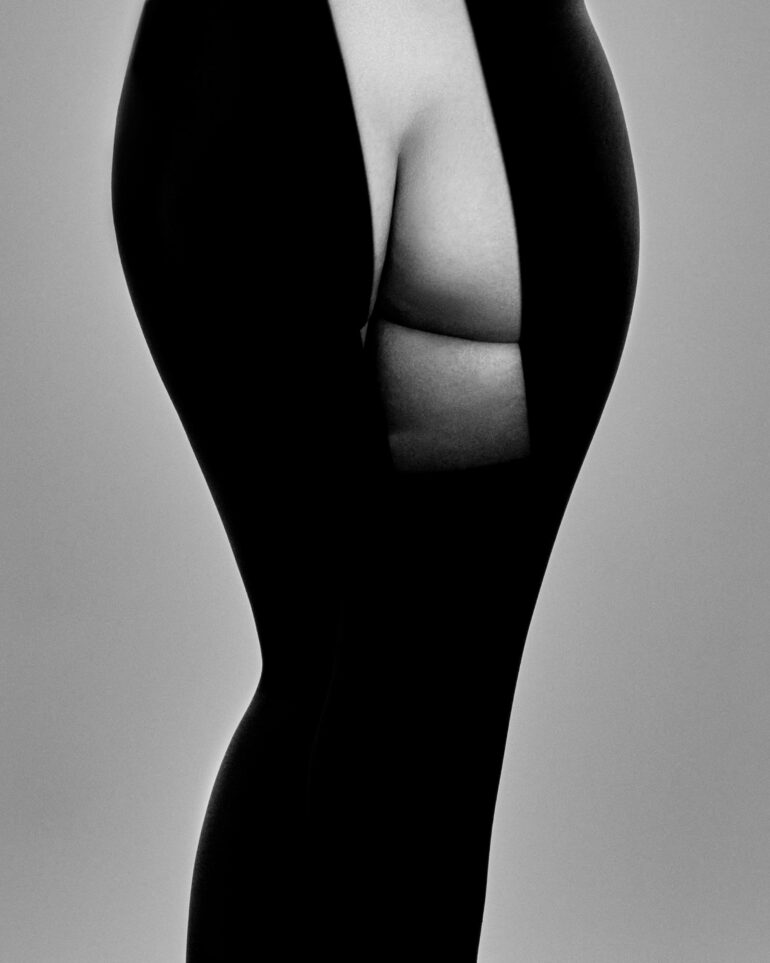

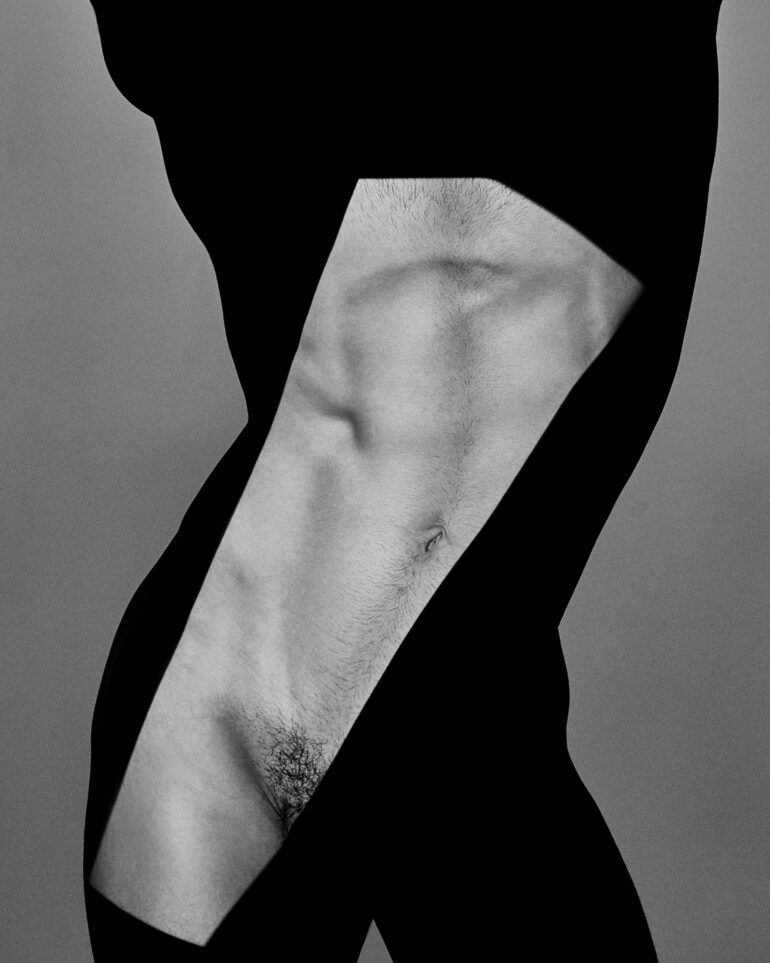

All images by Nicholas Freeman, used with permission. Please check out his website and his Twitter for more.

THE PHOBLOGRAPHER: How did you get into photography?

Nicholas Freeman: It started very early for me. My first introduction to photography was through my grandfather. He was an aerospace engineer who had a deep love for deconstructing things and learning how they worked. One summer, when I was around ten or so, we were watching Harryhausen films and I asked him how the stop-motion animation was made. Instead of just telling me, he went out and bought an 8mm film camera and showed me. We spent that summer creating our own stop-motion movies using dinosaur toys I had. My second big photographic influence was from my mother. She had a side hustle creating bespoke gowns for weddings and doing alterations. Our house was full of clippings from old Vogue-style magazines that she used for inspiration – but I got a lot of inspiration from them too, and a love and appreciation for the iconic fashion photographers of the 80s and 90s. In high school, I got my first digital camera and really started experimenting and developing my own style. It was a six-megapixel Fujifilm camera. After high school, I ended up going to Santa Monica College, which had an incredible technical trade photography program designed to get people working in commercial photography. I had intended to graduate and then transfer to Art Center to continue my education, but as luck would have it, I got some recognition in my classes and was given the opportunity to take an apprenticeship with legendary French fashion and celebrity photographer Dominick Guillemot. I ended up learning so much more and faster apprenticing that I dropped out of school and continued working with Dominick for six years. From there, I got the opportunity to work on my own with various fashion brands and editorials. In 2016 I got the opportunity to go in-house with PVH, the parent company of Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, and many other top fashion companies. It was literally a dream job and something I had been working towards my entire life, but during the pandemic of 2020, the whole team was laid-off. Currently, I work freelance for several big fashion companies as well as developing and transitioning to a fine art photography career.

Nicholas’ essential camera gear

Nicholas Freeman:

- Leica SL2

- Panasonic 70-200 f/2.8 S Pro

- Aputure lighting

I believe that the human matters much more than the gear. That a creative person could use any gear to achieve great results. During my career, I have owned and used almost everything. I have done commercial jobs on that six-megapixel Fujifilm; at one point, I owned multiple Phase One medium format cameras; on commercial jobs, I often use the companies’ Canon cameras and lenses; they are all tools, and you have to find the right one for the job at hand. I have to say, though, that when the L-Mount Alliance was announced, I jumped on it immediately. I have always loved Leica’s uncompromising designs, and to see them partner with Sigma and Panasonic to develop a system jointly seemed incredible. The camera body I use currently is the Leica SL2, and I am eagerly awaiting the announcement of the SL3. I have a pretty broad collection of lenses, but I recently noticed that almost all of my shots are around the 70mm focal length and so I am considering shedding some of that collection to focus more on the range I use.

My most used lens is the Panasonic 70-200 f2.8 S Pro which is a very well-designed zoom with very little breathing, which, while designed for motion work, actually helps me quite a bit in my exacting artwork. No matter what the job, the three lenses always on me are the 24-70, 70-200, and 105mm macro, although I hope to add a Leica Summicron 75mm f/2 to that list soon. With the nature of my work, I think it is also important to mention what kind of lights I work with. For the majority of my career, I have used Profoto pack and head systems, and I still do for most of my commercial work. But when I started transitioning to make fine art, I had an opportunity to change and evaluate what was best for me and my style. After many rentals and testing, I fell in love with Aputure lights. They are incredibly well-designed compared to similar lights at similar price points. While they are primarily marketed as cinema lights, they are also incredible for independent photographers. Currently, I make my art with various daylight-balanced LEDs, but I have also been doing some work that hasn’t been published yet that uses their RGB lights.

THE PHOBLOGRAPHER: The project that first caught my eye is “La Sombra.” How did you get to this concept? How do you manage to get such striking contrasts, working just in-camera? To expound on that, what do you think is the main difference between in-camera and edited work?

Nicholas Freeman: The concept for La Sombra developed rather organically. I was doing portraits for a friend, and we wanted to create a nude image that could be unedited on social media. The result was a nude silhouette with just the face illuminated and the light gently falling off before reaching the body. I fell in love with that look and wanted to see how far I could push the concept. The more I created with that original style, the more I began to see ways to change the process to create entirely new effects. Controlling the light in different ways could give me sharper lines, or lines that followed the body’s contours. Overlapping lights could give me surreal, almost abstract painterly effects. Cutting shapes in flags could provide me with custom shapes that couldn’t be achieved otherwise, allowing for shadows that appear almost as garments. The contrast is achieved through the actual lighting and the in-camera settings.

Many modern cameras will allow you to create custom looks within the camera, setting an amount of contrast, clarity, color handling, etc. In some bodies, you can even upload custom LUTs that you create straight to the camera. I am not using custom LUTs in my work, but I am intrigued by the option and want to play with the idea more. I also want to get this technique to a point where I feel comfortable bringing my film 4×5 out of storage and shooting the series on that again. I am by no means a purist, though. I think if the final result is better because of retouching or alteration, then that is the right choice for that piece of work. For me and this series of work, I felt it was best to keep it real. Because depicting bodies, especially nude bodies, can be such a sensitive topic, I made the decision to keep things real. To portray things as they are in reality, using the light as a method of curating, editorializing, and censoring the body instead of altering it. For me, the end result is rawer, purer, and more genuine, which is what I want with this series.

THE PHOBLOGRAPHER: How do you plan for these shoots? Do you have any routine you adhere to, or do you wing it? What would a typical workday look like for you?

Nicholas Freeman: Planning for these shoots can be difficult. Often the people I work with have never modeled nude before and sometimes never modeled at all. Because of this, much of the preparation is with the model, not the image. I spend time talking with each model, getting to know them, their experience, their comfort level with nudity, their boundaries, and whether or not they want to be anonymous or credited. I create a mood board of images similar to what we may do that day and discuss them with the model before the shoot. Something else I do that I have found great value in is that I sit with the models after the shoot and let them go through the images, giving them the opportunity to select their favorites and delete any images they object to. It is no loss if they delete a photo I like because I have gained a new idea and can recreate it with someone else who is comfortable with it. It is very important for me for the models to have faith and trust in the way I work, and that goes for every person I work with, from new models to celebrities. From an artistic perspective, I usually have one specific image I hope to achieve each shoot – if all I accomplish that day is that single image, then I am happy. If I am working with an experienced model, then that image will often be the first shot we work towards. If it is a new model, then my goal image will usually be the second or third image we work towards, to make sure they have loosened up and are comfortable in front of the camera. Once I feel like that image has been achieved, the model and I will often flow, letting one lighting setup or pose influence where we go next. A lot of my favorite images have been created spontaneously. But I find it is always important to go into a shoot with plans and a goal to keep from being disappointed if the spontaneity doesn’t work out.

THE PHOBLOGRAPHER: Personally, I love your work not just because of its gorgeousness but because it’s undoubtedly human in its conception; this is the kind of work nobody would even think to prompt an AI for. With that said, what are your impressions about these so-called “AI photos”?

Nicholas Freeman: I really appreciate the human description you give my work, as it is precisely what I strive to communicate with these images. Much of my in-camera art is a direct rebellion against what I have seen happening in the commercial world with over-editing and now entirely generated images. Although not there yet, I would like to do more completely analogue imagery. My feelings about AI-generated art are a bit complicated. I prefer the term generative art because they are definitely not photographs, and AI could mean many things. I think that generative art is inevitable and going to be revolutionary in the commercial art world. We will likely see it popping up in advertising and editorials all over the place. It is a cheap fast way to create content, and that is what commerce loves. I had a huge problem with the ethics of the early models who trained their data sets in unethical ways, scraping and stealing artwork from the internet. But new systems are emerging who have significantly improved their ethics, such as Adobe and Getty, who are training their data sets on stock images that they own and have contracts covering. In a world where the source material is ethically owned, I don’t have a big problem with generative art. It just becomes another tool available. I don’t think generative art will take much of a foothold outside of commercial and retail art. I believe that generative art will do very poorly in a fine art market. It lacks the depth and the human element that is essential in fine art. In the same way that photography did not kill painting or illustration, generative art will not kill photography.