Last Updated on 03/17/2023 by Lara Carretero

I spoke to black photographers to learn about their experience in the photo industry.

As February was Black History Month, my focus was predominantly on black photographers. Most people welcome that, and some don’t. My pieces celebrated black photographers and the work they produce. My pieces also highlighted some of the issues the black community is facing within the industry, which got me thinking, “Who am I, a white man, to tell people to care?” Of course, my voice is valid, but it’s far better to let black photographers share their experience.

Speaking to Black Photographers

For this article, I reached out to several black photographers, male and female. Some didn’t want to take part. Others didn’t respond. Reasons for declining varied. Sadly, I saw a pattern: photographers were worried if they spoke out, it would impact their careers.

The two photographers who were happy to comment are seasoned pros. They’ve seen it all and had careers that would make most jealous.

First, I spoke to Matthew Jordan Smith. He’s a Nikon Ambassador and has worked worldwide, receiving many accolades along the way. I asked Smith what his thoughts were on the experience of black photographers throughout his time in our industry.

“Throughout the history of photography, the viewpoint of Black photographers has been rarely seen. Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee changed this to some degree, but today we still have a long way to go. The Black Lives Matter movement brought on after the George Floyd murder definitely helped to shed light on how unequal and unjust America has been. In the months after the BLM protests, companies were actively looking for Black photographers, and I hope that this continues so the visual voice of America can include the visual voice of Black photographers.”

— Matthew Jordan Smith

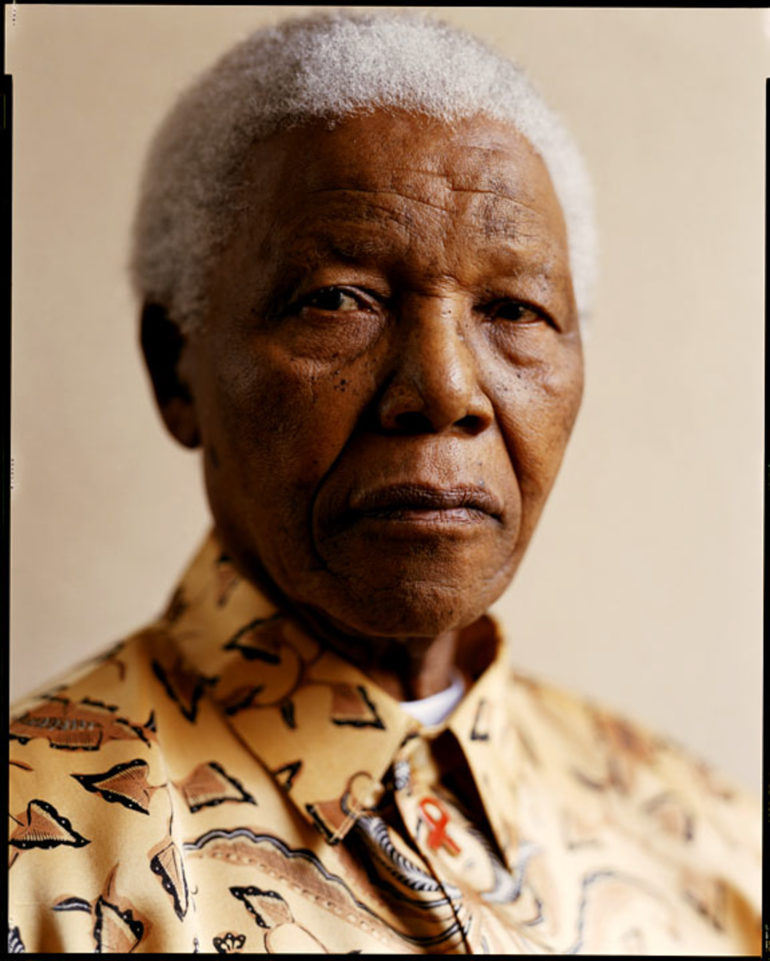

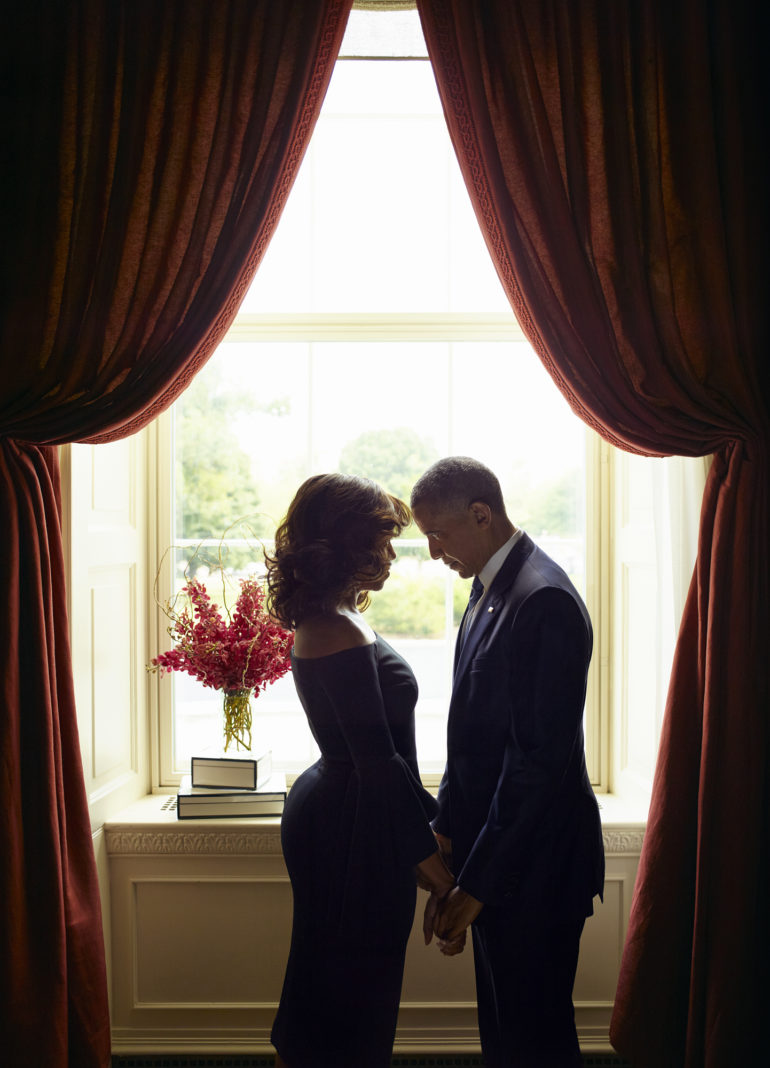

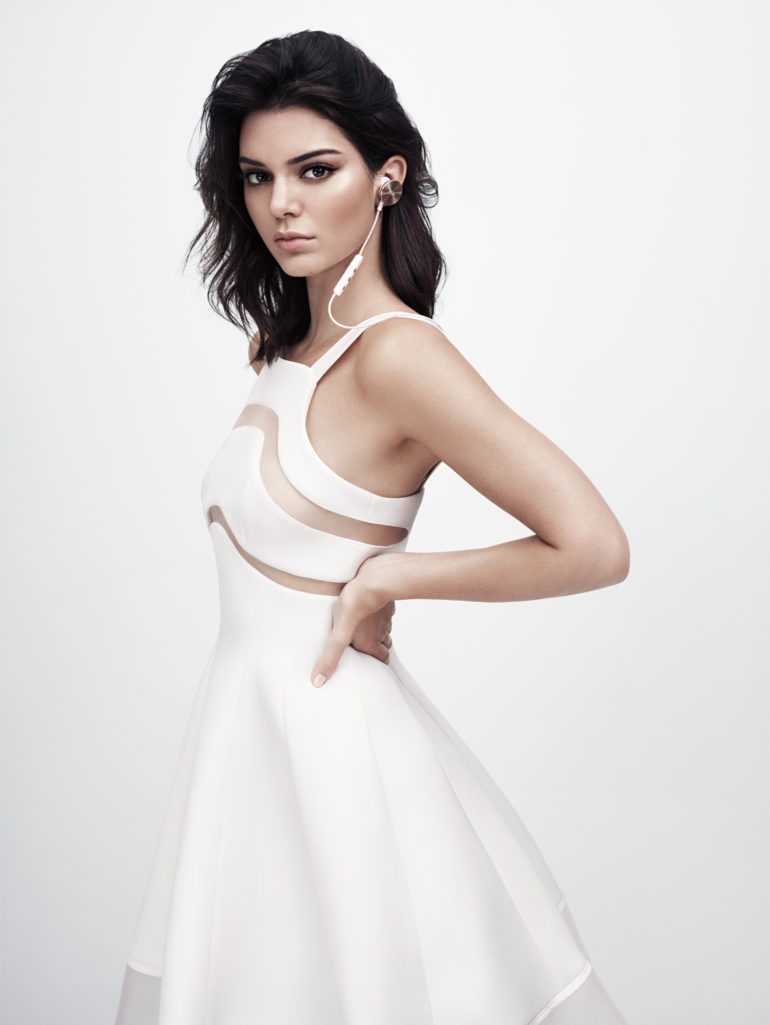

Smith then put me in contact with Kwaku Alston. A photographer I’m already familiar with due to his impressive portfolio. He has photographed many celebrities, including the cast of The Black Panther. If the photo industry has its own A-listers, he’s one of them.

Our conversation went much deeper. It was almost as if these questions blew the lid off a bottle that had wanted to burst for decades. It’s an education for anyone curious about the black perspective within the industry. And I thank Alston for being so honest about his experience. Take a look.

Phoblographer: Can you please give an overview of your experience within the photo industry as a black photographer?

Kwaku Alston: My first thought is that my “experience” is not just about being black in an industry, but about the whole concept of blackness and how that shapes a certain conversation within American culture.

It’s difficult to escape a certain narrative when you’re a black photographer, specifically the African or African American narrative. When you take this narrative to a realm like advertising (and I’ve certainly done a lot of work shooting ads), well, there’s a huge responsibility that goes with such a powerful visual medium.

I often feel like I’m at the crossroads or intersection between certain cultural gatekeepers and my own culture. How people see themselves is shaped by how they are represented in the media, pop culture, advertising, etc. I feel it too, as a creator and a consumer. Images play a key role in how we shop, interact with each other, view ourselves, and inform us of our history and legacy.

Phoblographer: Can you give a specific example of where being black has led to a negative experience during your career?

Kwaku Alston: Pretty early on in my career during the late 90’s and early 2000s, I started to wake up and see how images made by some of my non-black contemporaries were not always depicting people of color in a multi-dimensional way.

I can’t say they did this consciously. But the imagery of black culture in the media from the 80s to the early 2000s didn’t represent the full extent of our culture. African Americans are not a monolithic group. But when it comes to pop culture, we seem only to be represented visually by trends created by entertainment media.

Simultaneously, I was occasionally not seen as “black enough” – even though I certainly am black. So, when society got all kinds of images from the music industry – let’s say hip-hop – certain, not so positive images came to be seen as cool or as “authentic” to that culture. I don’t want to lean too hard on what is negative (or positive) here. But I believe that photographers of color rarely shaped pop culture, which has consequences.

On Representation

Kwaku Alston: Representation does matter. Of course, people have been arguing about this for a long time; I remember the conversation getting pretty hot when I was photographing hip hop artists back in the 90s. Rather than dwelling on what I think is negative or positive, I’d rather just say that I believe we can depict things with dimension, that we can tell stories that capture “more” and get beyond the usual clichés.

It all comes back to working on craft and deepening artistry. The images will follow. But with that being said, I still think it’s important to understand our roles and our influence as black image-makers. We have a voice, and we should feel free to use it.

So, if you’re a person of color and you question the hypocrisy of, let’s say, a marketing campaign or editorial, or challenge what’s being presented, you can become the outlier. You become the black guy that’s not down or not hip enough. It’s weird. I’ve had white photographers tell me that I’m not black enough and that they understood black culture more than I did. An added irony is that for whatever reason, it has often been easier for them to cross over and show so-called “urban culture” and present it as authentic black culture and then claim their spot as being “down with the brown.” And they reap the rewards that come along with that position.

But over this same period, for a black photographer to cross over and photograph an A-list white actress for an A-list magazine cover was pretty much unheard of (I’m talking about the 80s, 90s-and even up until recently).

–Kwaku Alston

At times there was a belief that we, as black photographers, could not possibly understand how to relate to what was visually necessary for those kinds of jobs. Maybe other factors were at work here too. Was class an issue? Was it a cultural connection, emotional relatability? Gender? I don’t have the final answer, but the proof is in the pudding — look who got those jobs. Hint: it usually wasn’t people like me. Thinking about it now, it didn’t feel like we were really able to take charge of how we were represented in media (on either end of the camera) until social media came along and changed everything.

Phoblographer: What would you say to up-and-coming black photographers who may feel their race will lead to fewer opportunities in the photo industry?

Kwaku Alston: My first piece of advice is always to be yourself, study your craft and be humble. No matter what happens. My next piece of advice is to save your money because someday you may well need it to reinvent yourself. And if you’ve saved up, that makes it a little easier to say no to what you don’t want and yes to what you do want.

But I feel strongly about never letting race define who you are as a person or artist. If people want to hire you because you’re black, that’s fine, let them. And don’t feel bad or awkward about it. It is their issue, not yours. Your work is always to make the best pictures you can – pictures that express who you are as an artist, let the universe take care of the rest.

We are at a pivotal time in American history where we are presented once again with the ugly face of racism in mainstream culture. It sucks. I really thought things were getting better. But we can do something about it now. We can be the gatekeepers of our image. In fact, I’d argue, it’s our responsibility to do so. We can forge a new narrative, and we can make it a world narrative if we want. We can include people, places and culture and land far beyond these 50 states.

There are many more stories to tell, and we’ve got a global canvas to work with. I really hope the next generation, the young guns coming up, understand their part in shaping a new narrative. When they do good work, when they function as gatekeepers and global storytellers, they create a legacy for themselves and for the generations that follow them. Yes, they can better tell the story of people of color and of American culture. But their work can transcend all categories as it tells a variety of stories, depicting human culture all over the world.

On Black Photographers Only Getting Black Work

Kwaku Alston: I want the young guns to understand that being hired for a so-called “white” high-end magazine as, say, the first black photographer to do this kind of work for that magazine, means nothing if they only hire you to shoot black work when they do hire you.

No one ever asks a white photographer if they can shoot an African America, Asian, or Latin-X person. They can shoot it all. And so can a black photographer. If you practice your craft and work hard, and you’re good at what you do, that’s what matters. Hell, you don’t ask a doctor if he can only operate on a man of his own race for heart surgery.

The concept is crazy; it’s racist to give black people only black work. Is this just a guise people use to hire us? Are we not allowed to get beyond our own racial category? What if we want to take a worldview?

— Kwaku Alston

There’s a fine line to walk when you are a person of color in the photo industry. You have the demands of navigating a challenging career path with all the trappings and pitfalls if you happen to make it to a level of success where you can pay your bills (and then some) for over 10 years. But all of that career navigating aside, there’s another line you have to walk: consistency in your art practice. Doing good work and growing in your craft always has to be there. So here I go again: Work hard, study hard, be humble. And save your money.

One more thing. Looking back, I feel like I’ve done a pretty good job of navigating this career professionally and artistically. I had some help along the way with some great mentors of all types, and I encourage younger folk to seek out those voices. It was always part of my career to play that role for the young guns coming up. We are here, and we have a lot to share.