Last Updated on 05/25/2023 by StateofDigitalPublishing

All images by Bruce Osborn. Used with permission.

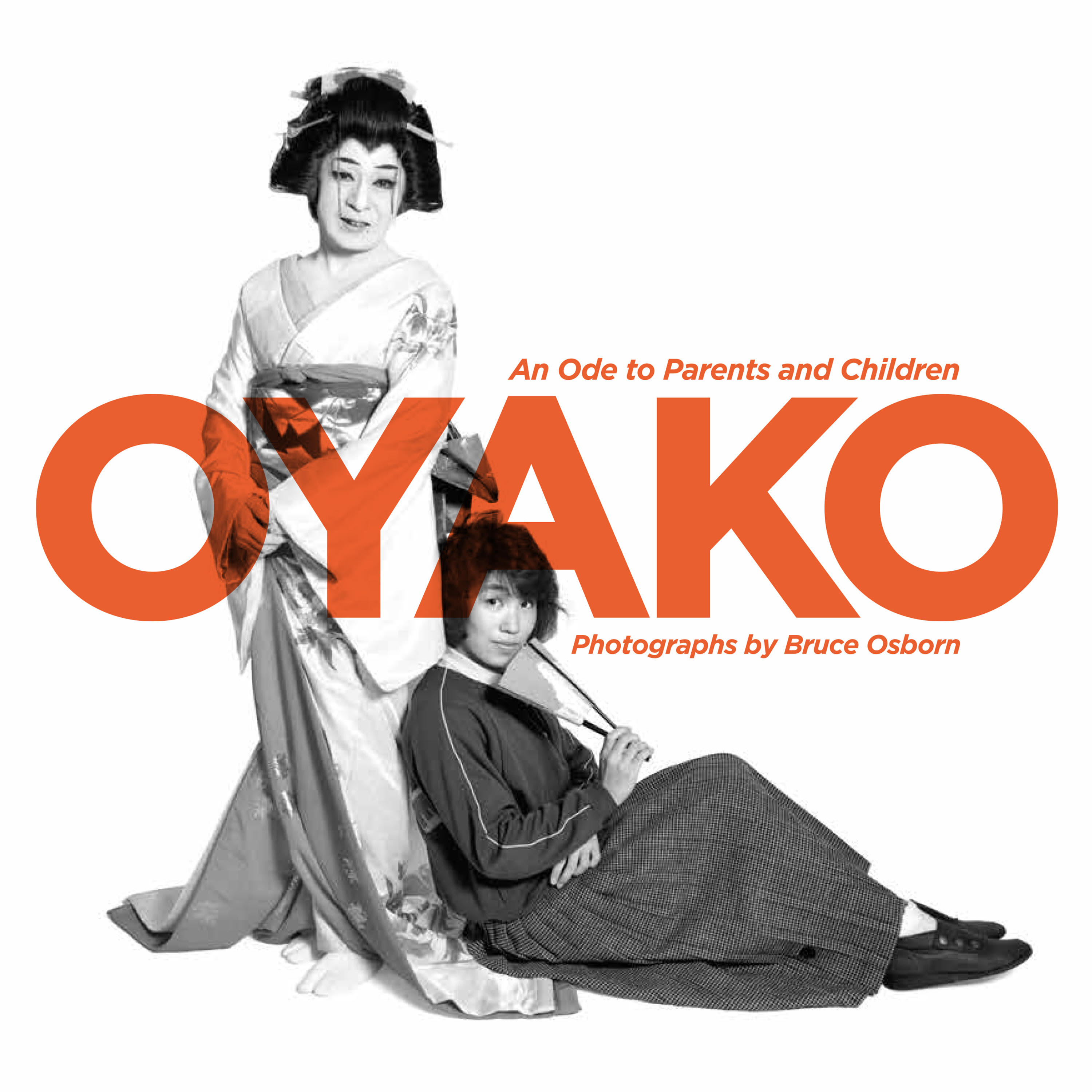

While there’s nothing new about family photos and parent-child portraiture, an out-of-the-box idea can breathe new life to them as an interesting photography project. Case in point is the work of Tokyo-based Bruce Osborn titled OYAKO: An Ode to Parents and Children, which gives us a peek into the relationship and dynamics between parents and children in Japan. The idea for this series — which has been made into a book as well — came while he was doing another assignment, but more than just a side project, it evolved into a more meaningful pursuit to share a slice of Japanese life and culture.

“The pictures were such a surprising insight into family relations that it encouraged me to continue exploring the parent/child portraits as a way of looking at Japanese society and the changes it goes through from one generation to the next,” Osborn said of his project.

In the insightful interview below, he tells us more about how the project came about, the inspiration behind it, and an interesting anecdote about one of the pairs he photographed.

Phoblographer: Hello Bruce! Can you tell us something about yourself and what you do?

Bruce Osborn: I am originally from Southern California and I have been based in Tokyo since 1980. My work can be seen in a number of publications and advertisements in Japan and overseas. I’ve received a number of awards and recognition for my photography, published several photo books, and had a number of large exhibitions. My most extensive collection is the photo series on Japanese parents and children, known as OYAKO: An Ode to Parents and Children.

Phoblographer: How did you get into photography? How did you discover the kind of photography and imagery that you make now?

Osborn: When I entered college, I wasn’t sure what to choose for my main area of study and took many different courses. Eventually, I found myself in the art department and instantly knew that I had finally found what I was looking for. I loved painting, drawing, and sculpture, but photography became my passion. To this day, I need to draw in my sketchbook when I am working on an idea for a photo and an empty studio feels like is a blank canvas I need to fill with my images.

Phoblographer: Please tell us about your thought process for your new book, OYAKO: An Ode to Parents and Children. How did this project come about? What was/were the inspiration/s behind the project?

Osborn: My OYAKO series started as a result of an assignment I had to photograph punk musicians. I was thinking about how to take them, when I hit on the idea of photographing them with their parents. I thought it would be an amusing way to bring out the differences in lifestyles and fashions between the two generations, but what came back was infinitely more. The pictures were such a surprising insight into family relations that it encouraged me to continue exploring the parent/child portraits as a way of looking at Japanese society and the changes it goes through from one generation to the next.

As I got further into this project, I thought it was interesting how Japanese had the single word OYAKO, compared to “parent and child” in English. I felt it was an indication of the different way that these languages saw this relationship. In Japanese, parent and child are combined into one unit, but in English, they are as separate individuals.

OYAKO: An Ode to Parents and Children is the first time for me to publish a book on this series that is geared towards people who are living outside of Japan. I hope the photos along with comments from the parents and children in the book will give insights about their feelings about family relations. Needless to say, the love that exists between a parent and child is universal and it transcends languages and cultures.

Phoblographer: How did you scout the subjects for OYAKO and explain to them the ideas/goals for the project? How did they react or contribute to it?

Osborn: When starting this series, I wanted to photograph parents and children who had interesting jobs and/or distinctive uniforms. My studio was located in the downtown part of Tokyo, in an area with an abundance of older and more traditional family-run businesses. I found many of my subjects living in the neighborhood. On the flip side, I was taking record covers of Japanese bands and shooting fashions for magazines. I was meeting a lot of hip creative people and I was also asking them if I could photograph them with their parents.

Most of the families didn’t understand why I wanted to take their portraits, but we had fun when I taking their pictures. When I had the opening reception for the exhibition, I invited all the subjects to come see the show; punk musicians, carpenters, tattoo artists, firemen… It was mix between modern and traditional Japan. But when they saw the photos hanging on the walls, everyone was moved on how this everyday subject of family portraits, could show so much about Japan how it is changing.

After this first show, I have gone on to take thousands of parent/child photographs. Though I am still interested in photographing people in their work clothes, I find myself wanting to look beneath the outer shell and focus on the unique relationships that exist between each parent and child.

Phoblographer: Please tell us about your gear of choice for this project. How do you think it allowed you to achieve your creative vision?

Osborn: When I began my series on parents and children, I was shooting with Hasselblad and Mamiya cameras. Fifteen years ago I switched over to digital cameras and my Olympus camera has been supporting my project since then.

The way I approached the subject of OYAKO is quite different from my other work. From the very beginning, I decided to always take the photos in a similar style; full-length figures, against a white background, and processed in black and white. I wanted to make it simple, without other distractions, so the focus was on the parent and child and their relationship. The parent represents the link to their family’s past and the child, a bridge to the future. Standing together, I see their past, present, and future. We are all part of an unbroken chain that goes back to the beginning of life itself.

Phoblographer: Of all the parent-child pairs that you photographed for the project, whose life and/or story did you find most unique or interesting?

Osborn: There are so many, but here’s one. I took a photo of Yuichiro Miura and his son Gota when they were preparing for their attempt to climb Mount Everest. The father was hoping to regain his title as the oldest person to ascend the peak. As the photo session was winding down, I asked if there was anything else that they wanted to try before we finished. Gota immediately squatted down, stuck his head between his father’s legs, and stood up. Yuichiro was caught by surprise, but regained his composure and stretched his arms out to complete the pose. A year later, they successfully reached the summit of Everest and the 80-year-old Yuichiro once again setting the record for the oldest person to make the climb, a mark that still stands. This photo symbolizes their relationship and the teamwork they shared to achieve that milestone.

Phoblographer: Which aspect of Japanese parent-teacher relationship/dynamics did you feel was most important to highlight in this project?

Osborn: The parent-teacher has an important roll to pass the culture on to the next generation. This is particularly true for traditional arts such as kabuki, ikebana, and tea ceremonies. However, the Japanese society is always evolving and even these foundations of their culture are changing. It necessary for the student-child to learn about their history and traditions, but the reverse is also true; the parent-teacher can also gain from listening to his student.

Phoblographer: What was the most challenging part of shooting for and putting together OYAKO? How did you work around it?

Osborn: One of my biggest challenges was how to take this project to another level. My wife and I had gotten such a wonderful response from this series and we wanted to create a social action to think about the parent/child bond. We establish Oyako Day to commemorate the special bond between the parent and child. To celebrate our first Oyako Day in 2003, we invited 100 families to the studio to have their photos taken. It was such a success that we have continued doing this event every year since.

In 2018, we had our 16th Oyako Day, which was celebrated on the 4th Sunday of July. In addition to my super photo session, there are now a number of other photographers who have started having their own Oyako Day photo sessions. It has also been recognized by Professional Photographers of Japan, The Photographic Society of Japan, and Japan Professional Photographers Society. Our dream is to see this project grow and eventually become as well known as Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.

Phoblographer: Which aspect of your style do you feel makes your work truly your own? In what way does it manifest in this new book?

Osborn: Instead of trying to direct my subjects on how to pose, I prefer to create situations where we can share in the process of making this photo. My image of the photo sessions is similar to musicians getting together for a jam session. Typically, I start off taking pictures at fast pace. It helps to keep their actions spontaneous and to get them over any nervousness. As they are feeling more relaxed in front of the camera, a rhythm develops between the subject, me, and the flash of strobe lights.

Phoblographer: Lastly, what would you advise those who are looking for interesting subjects for their photography projects?

Osborn: My advice is it good to think about what you want to achieve before begin a new project. However at some point it is important to stop planning and to start taking photos. There are always so many things that you didn’t consider until you actual are doing it. You must have heard it said times before, but it’s very true; “Don’t be afraid of making mistakes. You can learn more from your failures than you can from your successes.”

Visit Bruce Osborn’s website, to view the rest of the photos from OYAKO, as well as the Oyako Day website. You can also grab a copy of OYAKO the book on Amazon US and watch the trailer for the documentary movie about the project.