Last Updated on 02/07/2021 by Mark Beckenbach

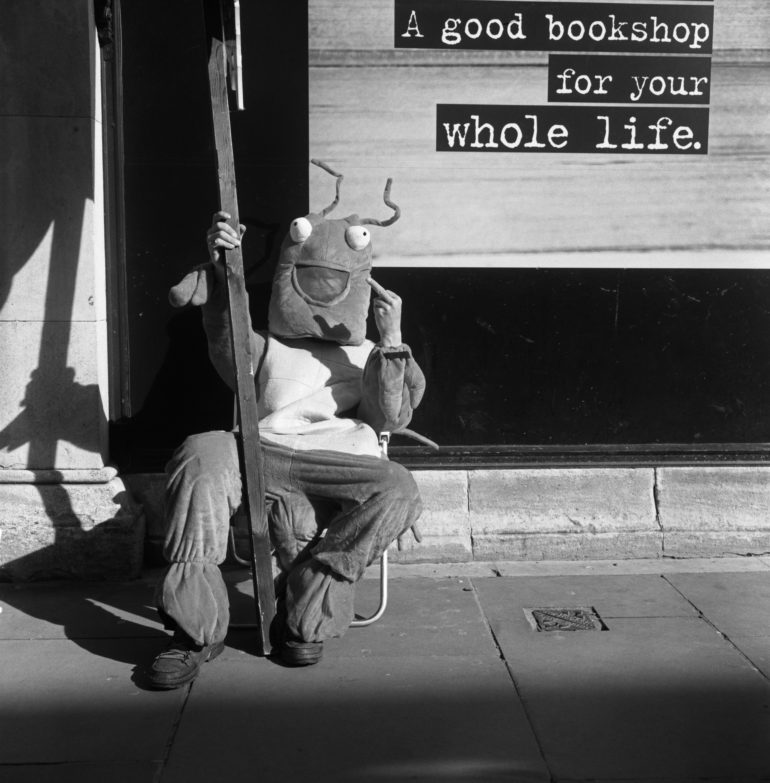

All images by David Stumpp. Used with permission.

Any form of art requires practice, even if it’s something as subjective and loosely defined as street photography. You give it time, make the conscious effort to improve your craft, and track your progress. How much time exactly do you need to devote to it? Well, it’s all up to you. It can even be as short as sneaking it in your lunchtime, as UK-based street and documentary photographer David Stumpp has done.

Among the things that Stumpp’s The Lunchtime Portraits have helped me realize is that persistence and consistency are key to getting ahead in any creative endeavor, photography included. It doesn’t matter if it’s just a few minutes of your break or you only get a handful of frames per day — as long as you make practice a part of your day and schedule. Of course, I wanted pick his brains about this project. In the interview below, I asked him about his beginnings in photography, where the idea for his lunchtime habit came about, and how the project made an impact on his work and style, among other things.

Phoblographer: Hello David! Can you tell us something about yourself and what you do?

David Stumpp: I am a native of Riverside, California, but I have lived with my wife in the United Kingdom for nearly a decade and, as of the past two years, I am a proud daddy. I have a degree in Music from the University of California, but professionally, I am an early-printed books cataloguer at Christ Church Library in Oxford, and I am also one of Christ Church’s photographers, for which I frequently do staff portraiture and event photography. Outside of paid work, I am a documentary photographer, recording the human experience and whatever else happens to catch my eye in just the right way.

Phoblographer: How did you get into photography? How did you discover the kind of photography and imagery that you make now?

Stumpp: A friend once complimented me on what I had only thought of as vacation snaps, and she encouraged me to do more. I’d never really considered doing photography for anything more than holiday memories. I’ve always had interest in gadgets and science, though, so the idea appealed to me, and after a couple of more rudimentary camera purchases, I finally bought my first semi-professional digital camera. As I was learning to use it, I realized that a digital camera essentially emulates a film camera and that the best way to understand my new equipment would be to know as much as I could about film photography starting from the basics, so I set out to learn. I read books (Ansel Adams’ The Camera and The Negative, for two), studied extensively at the universities of Google and YouTube, read forum conversations, and I practiced. And practiced. As I learned, I came to prefer film photography, because I enjoyed the increased involvement in the process of making a photograph from start to finish.

Phoblographer: We’d like to know more about The Lunchtime Portraits series. How did the idea come to you? What served as your inspiration for this project?

Stumpp: It’s difficult to talk about inspiration without mentioning my entire approach to photography. I do have occasional projects that come to mind, which I then work to carry through to an end, but, in general, I don’t tend to work from a premeditated inspiration. I think of photographs as almost having an existence all their own, independent of a photographer with a primed and ready camera. One day, on a lunch hour in my first year in Oxford, it occurred to me that, from a bare, subconscious level of my attention, I often observed photograph after photograph, flashing into being and then dissipating, on a daily basis. I was resolved from then on never to be without a camera and, also, to pay more attention.

I don’t pose people. Once in a while, I will talk to them first and ask if they would mind being photographed if I feel that it will further my cause, but the portraits that I am taking are not so much of the people, themselves, but of the moment in which they’re involved. I am taking portraits of humanity (and sometimes the animal kingdom, although even in those photographs, I see an element of humanity). I shoot almost entirely in black & white, partly because I can do the whole process at home, partly because I can better afford it, but mostly because, aesthetically, I just like black & white images better.

Phoblographer: For some photographers, one hour may or may not be enough to scour the streets for scenes to photograph. How did you make sure you’re making the most out of this lunchtime practice?

Stumpp: Oh, to be sure, it’s often not enough time, but it’s impossible to predict in advance how much time would be enough, anyway. There are days when I go out on a lunchtime walk and return, having only gotten a little exercise. I don’t find this to be discouraging. When a photograph is happening or I sense its potential, I just know it, and this is something that has proven consistent enough that I don’t worry about the days when I’ve not taken a single photo. What’s more, I like to avoid taking pictures for the sake of doing so, something which usually results in a wasted frame.

As to making the most out of it, that was simple. If I’m ever out walking with my camera at the ready, I’m likely having a good time. That’s all it’s ever been about. The fact that it turned into a project was almost incidental.

Phoblographer: We’re curious: Was there ever an interesting or unforgettable encounter while you were shooting for this project?

Stumpp: The day that I met a shirtless yogi wearing a turban, sitting cross-legged on a rug next to a basket set out for donations on Cornmarket Street with a sign offering free head massages is what springs to mind. I introduced myself to him and asked about what he was doing and if he wouldn’t mind a photograph. He was new to town, and he’d decided to sit there and give the massages as a way of meeting people and drumming up business. I took my photo, and decided to donate a pound towards his new life in Oxford. Once I’d done so, one of our resident homeless who’d been watching the whole exchange then lined up to have his photo taken, so I photographed him, as well, after which he stood with his hand held out, waiting. He’d decided that I was paying people to take their pictures. In the end, I gave him a pound, too.

Phoblographer: Can you tell us about the gear you used or this project? What made you decide to shoot with them?

Stumpp: Early on, I elected that my own photography would be done on film, because after a few years of doing big shoots on a digital camera with no sense of reserve and ending up with thousands of photos through which to wade, I greatly appreciated how film made me slow down, consider the cost of each shot, and evaluate my decision making processes. Digital photography has its place, but I reserved it for paid work for which I have to produce images in a timely manner. By the time I was taking the first photographs that would become this project, my everyday carry was a film camera.

I was doing this at a time when digital photography was still pretty young, but firmly established as the new paradigm. It was a time when veteran photographers were taking up their new digital equipment with determination and believing that film was on its way out, selling off their top-level film equipment, cheap, and it was during that time that I made many a killing on ebay. I spent years buying and trying, and either keeping or selling, so I could fund the next camera of potential interest. In this way, I eventually refined my preferences until I had a relatively small, but very personalized set of equipment, having used a test-drive process I would never have been able to afford a decade earlier. In the end, a Rolleiflex TLR distinguished itself as the best fit for me, so I bought a second, hoping never to be without one.

On this project, I’ve overwhelmingly used the Rolleiflexes, but I have, also, occasionally used a Pentacon 6TL, a Pentax Spotmatic, a Leica M6, and I think possibly a Canon F-1. Since buying my Pentax Digital Spotmeter, I seldom meter with anything else.

Phoblographer: Which part of this project did you find most challenging? How did you work around it?

Stumpp: I am an introvert. I hate being hemmed in by dense crowds of people. Taking pictures of strangers out in the center of a town packed with tourists was a real stretch for me but a useful one. All the same, I do think I use my camera as a barrier to an extent.

Phoblographer: You began The Lunchtime Portraits in 2009. In what way do you think it has affected or changed your photography since then?

Stumpp: It has made me fearless about photography, and, to an extent, dealing with people, whether it’s placating a subject who didn’t want to be photographed or making a new acquaintance over a chat about what I’m doing.

As well, the sheer volume of photographs that has come out of the project has caused me to consider their scope and purpose, as well as whether or not and how I might exhibit them. As I am nearing a decade anniversary of the project, I am hoping to publish my first photobook. Actually, my second photobook. My first photobook is about my daughter’s first year of life, and it’s been useful as a practice run. I plan to solicit the The Lunchtime Portraits to some established publishers, but I am prepared to publish it myself if necessary.

Phoblographer: What do you consider to be the most crucial element that makes your style truly your own?

Stumpp: Whether it’s obvious or not to anyone else looking at my photographs, to me, it’s the fact that I don’t think about what I’m doing. I might occasionally stand around and wait for a photograph that I suspect is about to materialize, and even give it some forethought, but when it comes down to the moment, itself, the actual framing just happens. Having looked at my photos after the fact, I’ve decided that my brain takes in the scene, boils it down to roughly blocked-in shapes, and decides on the composition, all in an instant. There have been photographs that I later considered practical failures, but I could nonetheless see how my instincts had blocked-in the scene and how the composition had made sense in the moment.

Phoblographer: Lastly, what would you advise those who want to develop their own street photography style or those who are struggling make time to practice their street photography?

Stumpp: Take your time. Be patient. Observe. Maybe even go out without a camera once in a while. It’ll hurt when you recognize that photograph getting away, I know, but using a camera because you have it in your hands is a great temptation, and being unable to use one will make you focus on the photograph and not the action by which it’s preserved.

Then, go look at the work of other photographers, and not just those that are making a name for themselves right now. Look at photographers all throughout the history of photography. See how the equipment defined their styles. See how photographic priorities evolved over the ensuing decades, informed by war, social conditions, fashion, or just boredom.

Most importantly, learn your craft. Learn the photographic process and how your camera relates to it. Turn off all your automatic settings and your auto focus, and develop your reflexes based on that knowledge, so that when the time comes and you’re standing face to face with that photograph, your hands and fingers will simply react.

Don’t forget to check out David Stumpp’s website to see more of The Lunchtime Portraits.