Last Updated on 07/03/2015 by Julius Motal

Adventure is the word many people would say when they think of National Geographic photographes. I certainly do. Thumb through the pages of any given issue, and you’ll see images from a wide range of often exotic locales. They’re images that not only look great, but they have something to say. Rarely do we give thought to what went into the making of those images. How exactly did they get the shot of that tiger, and how the hell did they get to the top of that mountain? These are questions worth considering, and those assignments are not without their pratfalls.

Bob Krist

Geographical and weather conditions can be some of the biggest challenges for any National Geographic photographer, and this was the case for Bob Krist, a long-time contributor to the magazine.

One of the most precarious situations Krist found himself in was an assignment in Iceland. It concerned puffins, but NatGeo had nearly every photograph imaginable of those birds. Yet, Krist found something different. In the course of his research, he learned that during the summer, Icelandic folk hunt puffins for food on the tops of cliffs. He enlisted the help of a local fisherman to take him by boat to the island of interest, and that boat ride coincided with a storm that bordered on the cinematic.

“We made our way from peak to peak of 20 foot waves, and occasionally, a frigid wave would just wash completely over us, so by the time he dropped me on a little outcropping on the leeside of the island, I was already wet, seasick and cold,” Krist said of one leg of the journey.

The man who ferried Krist over left him there with a storm still raging, and he wouldn’t be back for three days. Krist had to get to the top, and it was a nearly vertical climb. With no guide and just a hawser, one of those thick ropes that boats use, hanging down from a 450-foot cliff, he began his ascent. A third of the way up, Krist encountered the assistant of the man who ferried him over, and together they finished the climb. They remained together for three days subsisting entirely on smoked puffin, which Krist never got used to.

When it came time to head back to the main island, Krist’s original ride was nowhere to be found, having bailed in favor of a cod run, so the assistant helped take him back through terrible weather conditions. The weather did eventually clear, and the writer took a five-minute helicopter to the island Krist just left.

“They spent a sunny afternoon together, and she took the chopper back for the five-minute return flight. Which makes me think that when writers say they are smarter than photographers, they just might have a point,” Krist said. Despite this rather harrowing experience, Krist has given a sizable amount of time to covering Iceland, and he’s got a documentary called “A Thousand Autumns: Rettir in Iceland” slated to come out later this year.

Crises, of course, aren’t just limited to environmental experiences. Fear can manifest existentially, too, even when the assignment has its share of scary moments.

Bob Sacha

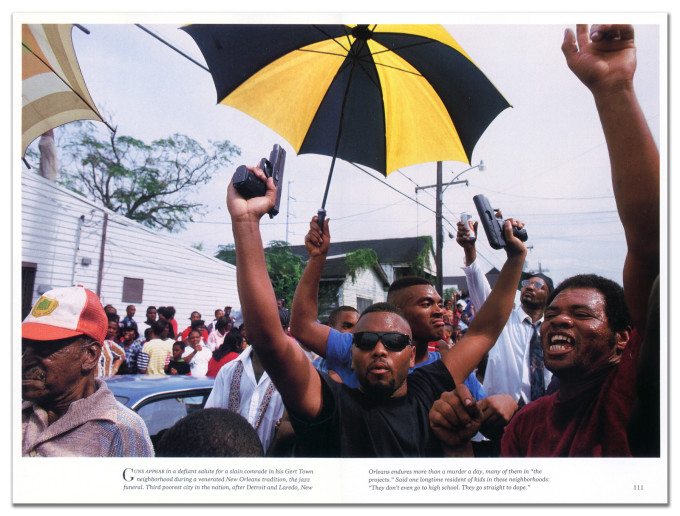

In New Orleans, Sacha was at a funeral parade for a gang member when one of the parade-goers revealed a pistol and waved it a bit too liberally. Sacha’s only recourse was to retreat into the crowd before anything could happen.

These episodes, however, where the danger was clear and present were not the ones that inspired the most fear.

“The truly scary moment was always in the days after receiving an assignment and the thrill wore off and the worry descended on how I was going to pull it off,” Sacha said.

This fear where you see the summit without knowing how you’re going to get there is one that doesn’t go away and can lead to things falling apart if there isn’t a clear plan. For Sacha, there was never any choice but to do it.

“I just put my head down and started working. It’s always hard but you have to start putting one foot in front of another,” he said. This isn’t relegated to photography as Sacha has since taken up video in spades both in his freelance assignments and his workshops (he’s still got spots open for this summer). The working-through one-step-at-a-time process is very much the same regardless of the medium, though there can be wholly unanticipated crises.

Amanda Rivkin

“Don’t trust Google Maps in conflict or post-conflict zones as the roads may be mined,” said photojournalist Amanda Rivkin who worked on two projects in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus with National Geographic Young Explorers Grants from the Expeditions Council.

Unless the area has been substantially surveyed, it can almost be impossible to know where landmines are. Landmine accidents are an uncomfortably common occurrence, particularly in post-conflict zones. In some places, landmines aren’t discovered until they’ve gone off. In others, they’re well documented like in the Falkland islands where there are cordoned-off no-go zones. Penguins there have, however, capitalized on them because they’re light enough to not set them off. People, however, are not so fortunate. When data or a “Beware Mines” sign isn’t available, your best bet is to talk to people.

“Talk to trustworthy locals and garner opinions that warrant merit. Sometimes, as we found out, it’s just a crap shoot,” Rivkin said.

Fortunately, Rivkin, Sacha and Krist survived their various ordeals and lived to tell the tale. In the moment, their crises may have felt insurmountable, but they made it through.