2014 was a year of one-day turnarounds. With a couple of days left in 2013, I decided to commit to a 365-day project that would force me to have my camera on me every day. Up until that point, photography was an occasional habit, and I’d read about how 365-projects have led to significant opportunities, though I didn’t go into it with any expectations. On the last day of the project (Dec. 31, 2014), I reflected on the project as a whole. In the time since, I realized that it was somewhat unwise to do a post-mortem the day it ended. No time had elapsed, and I was quick to pen my musings. That’s not to say that everything I wrote was invalid, but it was tinged with the pride that comes with completing a huge project. Now, four months out, I can safely that that project was the best and worst thing for my photography.

The rules were simple. I had to upload an image a day by 11:59:59pm that I made that day. It was against my self-imposed rules to queue up several images made on one day, and release them over a series of days. I only clarify that because that was a frequent question during the course of the project.

My first problem was that I spread myself too thin with platforms. Tumblr was the primary platform, which I had tethered to my Facebook and my Twitter, though the latter didn’t always work. I also posted to Instagram and sporadically to Flickr. It was a social media nightmare, and reinforced the notion that there are way too many platforms. That kind of upkeep is rigorous work, and in retrospect, I was only using the platforms as way to say, “Hey, look at what I’m doing,” which isn’t the worst thing. The problem was that I wasn’t giving anything back. I wasn’t interacting, and so I’d occasionally grouse and grumble internally when the reaction on any given channel was muted.

The tragedy of all of that was that I was looking for validation. I wanted, and in some ways needed, to hear, “These are great.” I flooded my very tiny island online with images in the hopes that someone somewhere with prestige and influence would see my work and give me a piece of that pie. There was no pie.

That’s mostly because a chunk of the images I made weren’t very good, and the reason they weren’t very good was the one-day turnaround. When there were interesting scenes to be had, making images wasn’t all that difficult, but when the day was dry, I was faced with a bad crop of photos. It didn’t feel good to put up an image I wasn’t terribly pleased with, but I had to put something up. Those were the rules.

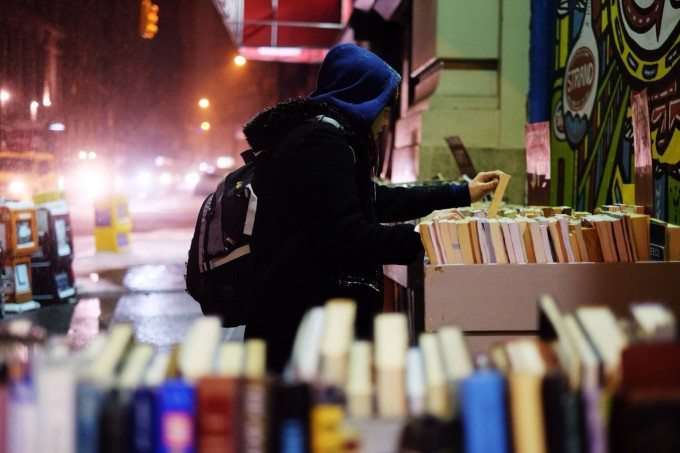

If it came to pass that I missed my deadline, I would end the project right there. The clock striking an imageless midnight was a kill-switch, and there were some nights when I came dangerously close. Those were the nights where the day wasn’t fruitful. With several minutes or an hour left to go in the day, I’d drag myself out of the house to make something, anything out of nothing, so that I could make good on my commitment. I don’t know what I would have felt had I ended the project early, but thanks to the encouragement of close friends and family, I trudged out of the muck.

It was forced photography, which isn’t necessarily a recipe for success. I had a handful of truly good images, with the lead image of this article being very close to the top, but when the photographs weren’t working, I had to either force an image out or force myself to think that an image looked better than it actually did, which was an abysmal way to go about things.

It was good, however, to be in constant practice, and the images were qualitatively better by the end of it, especially when I look back at the first couple of months. A style began to emerge. The subjects were clearer. The composition was cleaner. More over, it gave me an awareness that I didn’t have before, and in the months following the end of the project, I’ve made better images. Freedom from a 24-hour deadline, too, does wonders for my mental health.

It’s been better for me, too, to let go of external validation. Of course, it’s always a warm feeling to hear compliments about my work, but I don’t let it guide my work. During the 365-day project, I was, to some degree, shooting for the audience. Yes, it was a period of discovery, too, that is to say finding a photographic identity. I’m still searching for that, but at my own pace.

There feels like a constant pressure to put work out there, to be seen, to be on somebody’s map, given the wealth of publications and websites out there, and I’m the first to acknowledge my part in that. Getting past that project meant that I could just focus on shooting, rather than being seen, and it’s better, I think, to put out something fully formed than half-formed-not-quite-there-yet series.

My 365-day project was a half-formed-not-quite-there-yet series. There were seeds of ideas and some good images, and I’d probably be wise to pare all of them down to twelve. As Ansel Adams said, “Twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.” I’m not conflating my work with his. It’s just a good thing to have in mind, even though I most likely won’t pare those photographs down because I had to get through all of that to get better.

There were plenty of, “Why am I doing this?” moments. What’s a significant undertaking without an existential crisis? The project is, thankfully, over, and if given the chance to do it again, I definitely wouldn’t do it. Once is enough. I don’t need those kinds of self-inflicted headaches again.

I’m a better photographer now than I was before I started the project, though I’m not satisfied and probably won’t be for a long time. Having the freedom and space to create at my own pace is probably the best thing to come out of that project, and if you’ll excuse me, I have to go make some photographs.