Last Updated on 02/23/2015 by Julius Motal

All images by Hugo Passarello Luna. Used with permission.

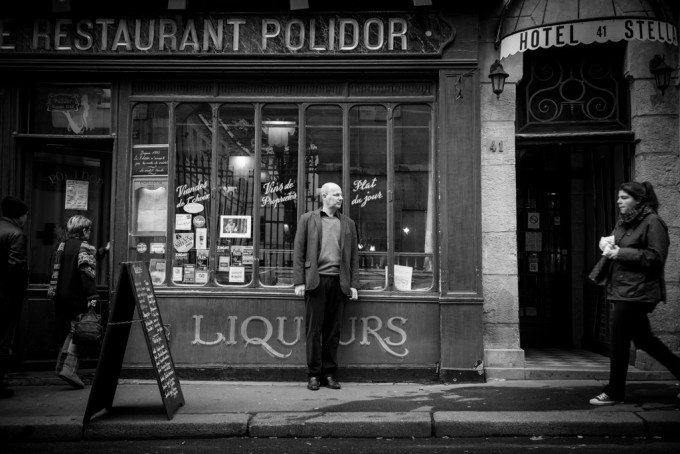

For Argentina and much of the Spanish-speaking world, 2014 was an important year. It was the centennial of the birth of Julio Cortázar, a central figure in the Latin American Boom, a major period in the history of Latin American literature. Hugo Passarello Luna is an Argentine journalist based in Paris, and given that Cortázar’s centennial would be big news, he wanted to find a way to honor it. So, he took inspiration from Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch, and developed the idea for a participatory photo essay. Cortázar spent much of his life in Paris, and most of the novel takes place in Paris. So, Luna put out calls on social media for readers of Cortázar. He would ask them to select a passage related to Paris, explain their choice, and then he would photograph them there. Luna worked on it for a year, and photographed over 100 people for it.

Phoblographer: This project is a massive undertaking. Where did you get the inspiration from, and how did you make sure you had enough time to work on this project?

Hugo: It was indeed an important undertaking, it took over a year to be completed and I am still taking some photos as people are still contacting me to see if they can participate.

Inspiration is a complex process, it comes from working, trying, checking what works, reading, and reworking everything again. I am a journalist so I am always on the look for stories. However I also like to explore different ways of narrating them. I knew 2014 was going to be filled with articles, interviews and retrospective about Julio Cortázar’s work, as it was the 100th anniversary of his birth. I wanted to see if I could take a different angle on this story.

The first thing that came to my mind was “participation”, to let people be part of the project. I am a freelance journalist, so I am used to working in solitude. So through the participative aspect I was looking to create a dialogue with the people I was going to photograph and the best way, I thought, to get them interested was to give them a role, a part of the project. They had to choose the passage of the book and then explain why they chose it.

Initially I only wanted to take around 9 to 11 photos and pitch them to a magazine in Buenos Aires to be published in a hopscotch format. But I ended up photographing around 100 people, because many more than I expected were interested in being part.

How did I make sure I had enough time? Well, time is, and I fear it will always be, a challenge. The only way to find time is to choose to make time available.

When I started the project, I had just signed a contract with a French TV station working full time as a journalist. I worked on my project during the weekends, at night and during lunch breaks. I took the decision to make my project the priority over other things. That meant sacrifices, but it paid back with satisfaction.

It is important not to get anxious and do things step by step. Even if you feel you are going slow and time is flying. It always flies. If you want to find a balance you have to come to terms with time, because you will never outpace it. If you don’t have to, don’t rush. Time is short but it gets shorter if you run. So walk.

Phoblographer: How, if it all, did Cortázar’s writing affect your approach to this project?

Hugo: My work had to reflect, somehow, Cortázar’s universe. One of the first questions I asked myself was “How to do an unexpected photo essay about a narrator of unexpected stories?”

His book Hopscotch appeared to me as the right springboard. This book has the distinctive feature that it can be read in two ways: from beginning to end, like a standard book or following a second order of chapters that the author provides. So the reader has to play around with the text, like we play hopscotch. Like the book my project had to be playful and participative.

I called it unexpected because I aspire to deliver participants and readers an unexpected experience. There is not one prearranged narrative sequence but many. They depend on the participants’ selection of passages and places; and on the readers’ choices. The audience will find several possible readings when “playing” with the images.

The book I made out of this project also follows these lines. I handmade 100 copies and I chose a book-object format. That means that inside a book shaped cardboard box, I included nine envelopes, one pebble and one chalk. The envelopes represent the hopscotch’s squares. Each conceals a photo. The reader has to arrange the envelopes in hopscotch format and then throw the pebble like if she or he was playing hopscotch and unveil the stories hidden within each envelope.

Each copy is unique as no single book-box hides the same combination of images. So the owner of the box 33 has a different experience from the one who owns box 21. It varies also according to the language as some boxes are in English, others in French and of course in Spanish.

It worked so well that I did a second mini edition, which is much smaller in size and it has five envelopes instead of nine.

Phoblographer: Why did you choose to photograph in black & white?

Hugo: I like color, but for this series I went for black and white because I wanted to play around with the idea of time passing by. Hopscotch, the book in which I based my work, was published in 1963 and despite the 50 years that went by I was surprised to find out that it is still read by young people, some of them who participated in my project. They told me this text talks to them even if the book is filled with an atmosphere of the Paris of the 60s, which is long gone.

The photos are in black and white to evoke a past time, yet people’s clothes, cars and other items clearly tells us that we are not in 1963. Same space, different time.

Also, while I was visiting the Parisian places named in the book I realized most of them stayed relatively the same, ignoring the passage of time. There is one specific place, in the geographical center of Paris, that Cortázar writes about, and he mentions a weeping willow standing alone in this small park. If you go today there is a weeping willow. No idea if it is the same, but I prefer to imagine it is.

Paris changes, but it does slowly. Different from Buenos Aires and so many other cities in the Americas where I have a feeling that buildings are finished just in time for them to be demolished and a larger building arises in the same place. The Latin American urban landscape is ever changing.

Phoblographer: How many people did you approach, and how did you figure out whom to approach?

Hugo: I photographed around 100 people. The first thing I did was to post the call on social media, mostly in Facebook groups of Spanish speakers in Paris. But I also sent out some emails to high school Spanish teachers, Spanish literature departments in local universities and so forth. Many people answered this way.

Once I started taking the photos and publishing them on my site word of mouth made the rest. Somebody had heard about my project through another person and contacted me. Also, the people I photographed would suggest me other persons that might be interested in joining. As I mentioned before I was planning to photograph only 9 to 11 people and I ended up with 100.

Social media helped me a lot but I soon realized that most of the people I was portraying were from a specific age range, going from 21 to 35. I wanted to find those readers that were outside this range. Cortázar had lived in Paris for over 50 years, he had many friends here. Reading articles here and there I found their names, I searched them on the white pages and I sent them letters, physical letters, inviting them to participate. People receive dozens, if not hundreds of emails, per day. Getting a letter in a mailbox, I think, made a difference and they took the time to call me back.

Phoblographer: This project seems like a good practice in community building, both in person and on social media. How important was the community aspect to your project?

Hugo: It was vital. The majority of the projects I’ve done in the past, I’ve done them by myself and though you learn a lot about yourself, I was missing a crucial aspect in the creative entrepreneurship: dialogue. My creative conversations were limited to discussing them with my girlfriend, with books (objects notorious for not answering back) and with some close friends over email. But I could not put the load on only one person, and email is not as good as a straightforward conversation face to face.

There is where the community played a key role. They were at the same time participants and, in a way, co-creators of the project. If time allowed, I would meet them before taking the photo, and we would have a coffee and talk about the project and also about them.

Every weekend, for over a year, I had a marathon of meetings. I would start at around 9am meeting the first person, talking and then taking the portrait. The second would be at 1pm, so I had time to get to another point of the city, and the third at 4pm, just before the sun would go away, during the winter of course. All my Saturdays and Sundays were like that. It was exhausting and some days I would just prefer to stay at home. But once I would start talking to the participants, and listening to their interesting stories I was happy to be outside with them.

I am not too sure if I built a community on social media, but I definitely built one in person. Thanks to this project I met way over 100 people from different walks of life. Once, while I was photographing a lady, a man walks by and asks me what was I doing. After I explain the project, he revealed he was a great reader of Cortázar, and he quoted me some lines of his writing to prove it. He is a French painter, a peculiar character, that can talk hours about painting and literature in romanticized manner. We talked a couple of times before taking the photo. If it wouldn’t be for my project, I don’t think I would have met someone like him.

Phoblographer: What was it like photographing Julio Silva, someone so close to Cortázar?

Hugo: The nicest surprise was when Cortázar closest friend artist Julio Silva answered my call, several months later after receiving the letter of invitation because he had been away from Paris. He was the only one who did not want to choose a passage from the book. He wanted to be photographed in Cortázar’s grave, which is decorated with a sculpture of Silva himself. He told me that when Cortázar knew he was going to pass away soon, he visited Silva’s workshop and asked him to make a sculpture for his grave. Silva answered that he could himself choose one from the many he had in his workshop. The one you can see in the photo.

Silva asked me to photograph him from behind because he did not want to be the center of attention of the image.

Phoblographer: In the course of completing this project, what did you learn?

Hugo: I learnt a lot about myself. As a journalist I have to work very fast on news stories that have, understandably, a short lifespan. You write fast, you interview fast, you photograph fast and then you have to move to the next story. I wanted to work at a different pace, in a story that would take me several weeks or months.

A slower pace allows me to better know the people I am working with, the subjects I am shooting, and the path I should take to improve my photography, videography and journalistic skills.

Many of participants were not used to be photographed, yet they accepted to join the project. So getting them relaxed was sometimes a challenge and there is no single way to do it, as people are very different. Sometimes you succeed in a few minutes, sometimes it takes hours and sometimes too, you simply fail. So you learn your limitations. Listening to them is essential to get them relaxed in front of the camera. And because I am genuinely interested in people, that is really not a problem for me.

I also confirmed what I have already learnt before, for example that despite being prepared and have some ideas about how the image should look, many times things do not go the way you expected so you have to improvise and be creative on the spot. Sometimes it works well, others not so much. But that is part of process. It is not a good idea to measure things as a success or a failure; it is more complex and more dynamic. It is an ongoing process that at times gives unexpected results.