Last Updated on 05/25/2018 by Mark Beckenbach

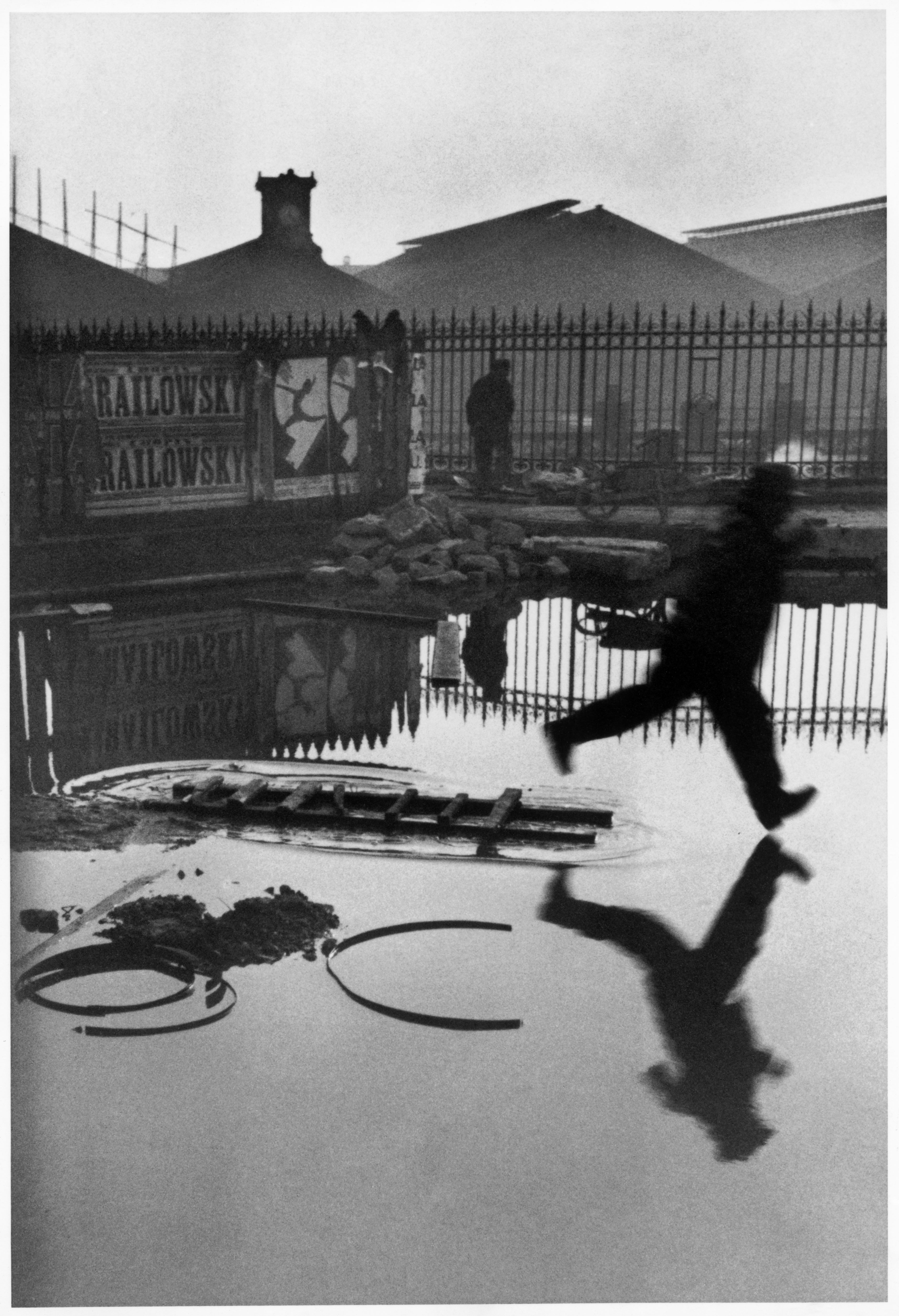

Believe it or not, Henri-Cartier Bresson hated the marketing term “the decisive moment.”

When we speak about Bresson, we often associate him with the idea of the Decisive Moment. But as I learned on a tour of one of the newest exhibits at International Center of Photography, he actually hated that term. The exhibit itself is coined “The Decisive Moment,” but to Bresson he believed that there are many moments instead. The artistic photographer also really seems to have wished that his now famous book would have instead been called something along the lines of “Images on the Run.” Indeed, this is a bit more like what we see of Bresson’s work, at least in some of his most famous images.

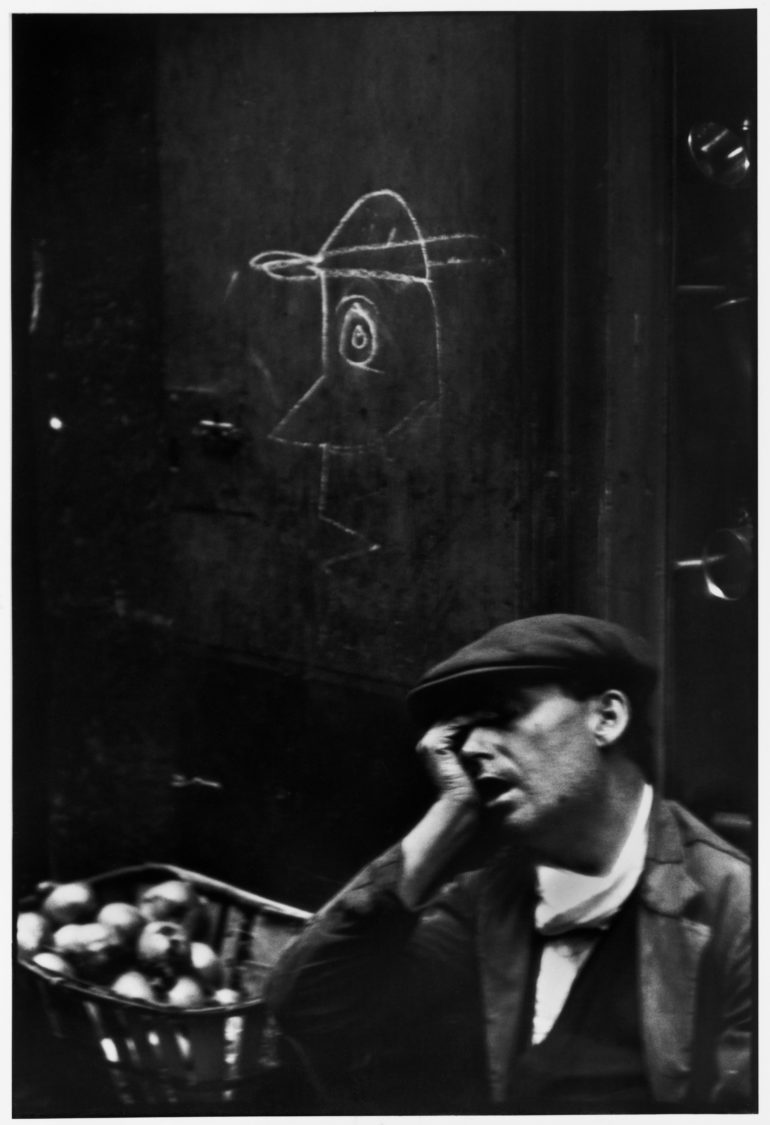

The narrow street of Barcelona’s roughest quarter is the home of prostitutes, petty thieves and dope peddlers. But I saw a fruit vendor sleeping against a wall and was struck by the surprisingly gentle and articulate drawing scrawled there.

When you enter the exhibit area, you see “The Decisive Moment” first. You’re surrounded by a blue wall with writing and the exhibit’s description along with a projection of many of Bresson’s images. Throughout the rest of the exhibit, Bresson’s images are neatly arranged along the walls in a very Plain Jane fashion. The avid gallery goer inside of me screamed in anger, wondering just why ICP chose to display such an important photographer’s work in prints that are fairly standard. But as I learned when viewing his exhibit on India, Bresson had specific instructions about how large certain images were allowed to be printed. Of course, his organization still maintains this standard. To that end, ICP does the fantastic job of using the final projector to keep people moving in a steady flow and one direction.

In addition to the images, you’ll see notes and letters from Henri about the creation of the book and his photos. They’re old and kept in very good condition. But they’re also behind quite a bit of glass. So if you’re going, I strongly recommend asking ICP for a magnifying glass in order to see the text.

The gallery’s curators did a fantastic job selecting which images of Henri’s to display. Seeing his images on a screen is certainly one thing but looking at a print of his close up and in person is something much different. Your eyes travel all around the photos, which are very well lit to minimize reflections of any sort. You begin to look, think and understand more of what he talks about with geometry. It’s very important to the image taking process for him. His influence can be seen in many modern photographers and with those who came after him.

Bressons’ images not only include those in his book, but also some images that have only recently been shown to the public from his time in India. What you see in much of his other work is that it’s all his through and through. By that, we mean that his then unique style played a big role in his pressing the shutter. Where this deviates is with his work in both India and Mexico.

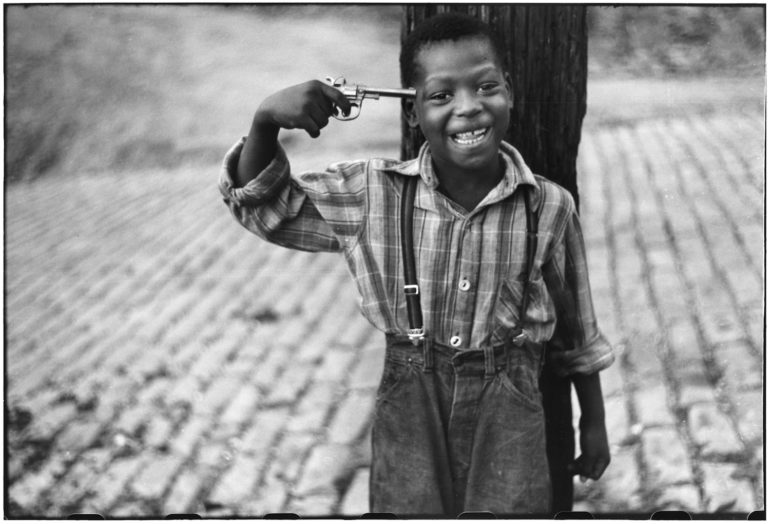

Henri’s work takes up a fairly large portion of the first floor, and in comparison Elliot Erwitt’s works (in another exhibit) are much smaller though arguably more important. Elliot was a true photojournalist amongst those who founded Magnum, Henri was the rich kid who cared about art and art first. Henri’s parents owned factories and he was well aware of some of the conditions and happenings in these areas. However, he never chose to document the stories inside. Where Henri’s work is important in advancing photography as an art form, Erwitt’s work does the same while also trying to advance the human race.

The exhibit overall is very good; in fact it’s the best that I’ve seen, far better than what the Rubin museum did recently yet not as all encompassing as ICP’s recent exhibit of Magnum’s history. But in the end, I walked away lukewarm. This doesn’t come from what ICP did or what Cartier has done per se. My feelings are more due to the fact that Bresson is highly prized and referenced in the same ways that Ansel Adams is. I joked with another journalist that many street photographers and documentary photographers romanticize Bresson’s work in the same way that many landscape photographers have shrines to Ansel Adams in their closet. He’s the introduction to the genre but after a photographer gets their identity together, they tend to move on and look at the work of Robert Capa and many others. To that end, I genuinely think that Elliot Erwitt’s work showcasing the industrialization of Pittsburgh deserved more room. In fact, perhaps that and Multiply, Identify, Her are the most important exhibits there. I strongly recommend carefully and slowly going through the exhibits there. Look at each more than once. It will do wonders for your thought process as a photographer.

All images used with permission from ICP