Most of the emails we receive from readers merit a quick response, since they’re usually something gear-related. Occasionally, we get an email that calls for a much longer response because of the question’s depth. This email comes in from Sharon Eylward who noticed that most of the photographs on this site are street photographs in which the people are unaware of the camera. Sharon wants to know how to practice street photography “without getting punched in the nose”.

It’s taken a while to figure that out, but here’s our answer.

The Letter

The Answer

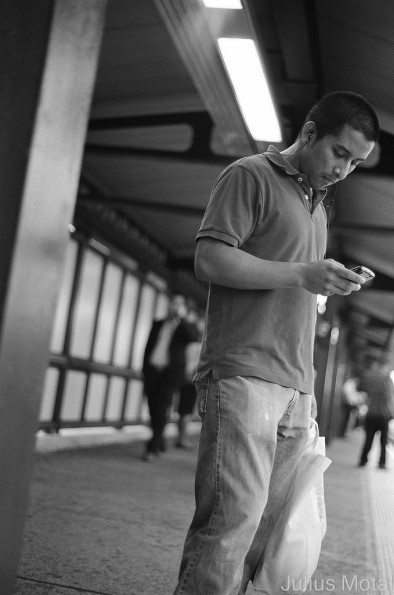

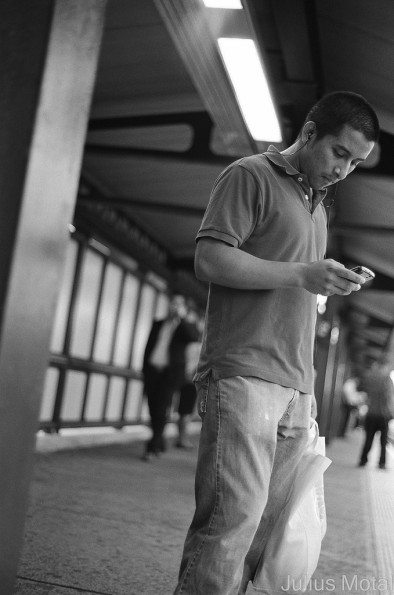

My first street photograph was of a guy using his phone on a train platform. The thought to photograph him happened rather organically, but it still felt like a risky venture. My Minolta’s shutter wasn’t exactly quiet, and pressing it at the wrong time could spark a conversation I wasn’t exactly inclined to have. But there I was with my camera vertically at my side and finger ready to go on the shutter. I pressed it, life continued, and I was pleasantly surprised to see that I got the shot when I got the roll back.

For me, when it came to street photography, there was always this pang of, “What the hell am I going to do if someone says something?” Confrontation really isn’t my bag, so I shied away from turning my lens on all the people around me. The more I stayed away from people, the more my photography stagnated. Photographs of inanimate objects with somewhat interesting composition can only go so far before its pizzazz dries out.

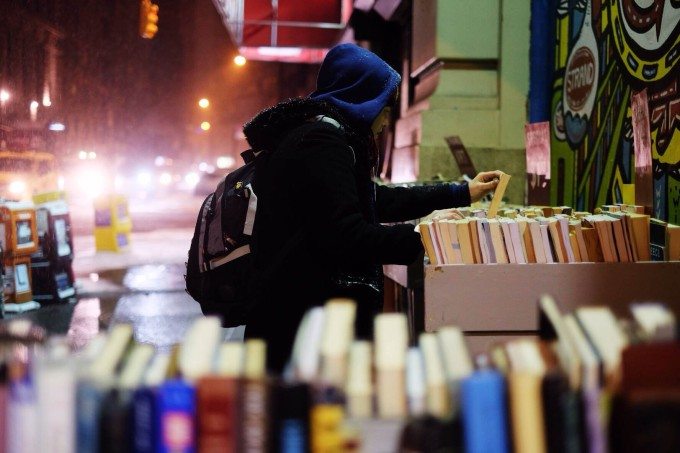

I soon realized that the most compelling photographs were of people I didn’t know on the streets of New York City, and it seems that Sharon recognizes that there are photographs to be made on the streets of her city, wherever it is. Whether my camera was at my eye or at my hip, I’d always keep my lens focused on the people around me. Granted, it took a while before I got the shots I envisioned, but it was through those early mistakes and frequent practice that my eye got better at determining moments.

There is a certain degree of surreptitious behavior to street photography, at least in my experience. You hang around and wait for the moment, or you take the shot while you’re walking and raise the camera at the opportune moment. If you want the shot to be honest, let the scene unfold in front of you. Don’t ask for permission, ask for forgiveness. Once you actively make yourself part of the scene, the image disappears.

To date, I have not yet had a confrontation, but I’m more than prepared to explain my intentions as a street photographer. To wit, I recognized a moment in which the person was a prominent player, and I’d be more than happy to show and share the image with them.

In the case of this image, Platina, the mother, was constantly interacting with her son across from me on the train. There were several moments that I recognized as photographs and I made them all. I also recognized that she would most likely want these images, but the thought that it could go horribly wrong also popped up. “Why are you taking pictures of my son?” was an easy question to ask, and one that would have made for a tense interaction. I found an in for conversation, identified myself as a photographer, and offered to send her the images. She responded warmly, and left the train with two images of her and her son.

There will be times when the person, or people, in the scene realize they’re being photographed, and that’s okay. Oftentimes, it will make the image more compelling. If you’re approached by someone you photographed, intentionally or not, be honest about your intentions. You are a photographer capturing scenes of city life. Keep some samples of your work on your phone, so you can give them a sense of what you do.

Mainly, it’s a matter of timing and where you are in relation to the photograph you’re making. More often than not, you’ll find that life continues after you’ve made the image. The person in your frame keeps walking, unaware that they were part of a moment you recognized. If you feel compelled to approach them afterwards, go ahead and talk to them. The most important thing, however, is to get the photograph, and it takes practice.